30th April 2000

News/Comment|

Editorial/Opinion| Business| Sports|

Sports Plus| Mirror Magazine

Star-struck stupas in ancient Anuradhapura

- Yes, I am positive

- Two winners and many similarities

- Tension and promise

- Panhinda

- Kala Corner - by Dee Cee

- A taste of Sinhala (17)

- Old man of the sea - Oddly Occupied

- Here we go again

- Medical Measures

- True colour of black and white

- Boost for Sri Lanka's eco-tourism

- When elephant's penis was a golf bag

- Rights violating: putting the public in the picture

- Stress on responsibility than freedom - Wolrd Press Freedom Day is May 3

- Day of small fry

- Romance that started with a photo - Down Memory Lane

- Inspirational moments

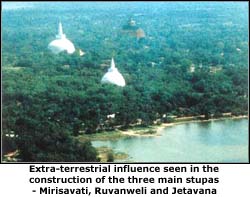

- Star-struck stupas in ancient Anuradhapura

- Making a difference with a drop - West meets East

- Emotional intimacy-key to a happy marriage

- News 100 years ago

- Dam the river,damn the forest

- Letters to the editor

The "greatest" AIDS activist in the region was let down by the very system she helped foster

Yes, I am positive

By Feizal Samath

She

wakes up at 6.30 in the morning and takes her drugs at 7. She tries to

have a heavy breakfast but doesn't like lunch though "I force myself to

eat it". Meditation, reading, dinner and late-night television "because

I have to take some drugs rather late" rounds up Kamalika Abeyaratne's

daily schedule apart from her work as an HIV/AIDS rights activist.

She

wakes up at 6.30 in the morning and takes her drugs at 7. She tries to

have a heavy breakfast but doesn't like lunch though "I force myself to

eat it". Meditation, reading, dinner and late-night television "because

I have to take some drugs rather late" rounds up Kamalika Abeyaratne's

daily schedule apart from her work as an HIV/AIDS rights activist.

Dr. (Mrs.) Abeyaratne had dedicated her life to caring for children in Sri Lanka and had a wide circle of friends until she discovered she was HIV positive after a "mercy mission" which virtually turned the clock back on her.

"Most of my friends then stopped coming home. Some of my doctor colleagues still cross the road when they see me approaching," says the 66-year-old paediatrician who now spends most of her time helping other HIV/AIDS victims.

Dr. Abeyaratne, became a victim in 1995 through a contaminated blood transfusion after injuries she sustained in a road accident while driving to a free medical clinic.

She believes support and care for AIDS patients is something that is lacking here. "The fact that Sri Lanka is seen as a low prevalence country in terms of HIV/AIDS doesn't help because people are scared to talk about it," she says.

According to government figures, the number of deaths from AIDS up to end August 1999 was 75, HIV positive cases totalled 286 while there are about 7,500 people living with HIV in Sri Lanka.

UN estimates however reckon that there may be 80,000 persons in Sri Lanka, infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, by the year 2005.

"AIDS

is a hidden phenomena in Sri Lanka and infected people are scared to talk

about the disease. So the official figures are not very accurate," Dr.

Abeyaratne said.

"AIDS

is a hidden phenomena in Sri Lanka and infected people are scared to talk

about the disease. So the official figures are not very accurate," Dr.

Abeyaratne said.

HIV or AIDS evokes public anger than empathy. AIDS patients and their families often face disastrous consequences if a village community is aware that an AIDS victim lives in their midst.

Dr. Abeyaratne has been chairperson of the AIDS Coalition for Care, Education and Support Services (ACCESS), a non-governmental organization since its formation in 1997. ACCESS helps and supports HIV/AIDS victims by visiting patients in hospitals and homes.

Earlier this year, ACCESS launched Sri Lanka's first AIDS hotline, offering free advice to callers seeking information on the disease. The response has been good so far.

Friends have described Dr. Abeyaratne's work in the AIDS field as courageous given the social stigma attached to HIV and AIDS victims.

"She is an extraordinary woman who has been discriminated by society after serving her country as a dedicated paediatrician for many years in state hospitals in Colombo and the rural areas," said Sherman de Rose, head of the gay rights movement, Companions on a Journey (COJ).

Rose, who is also ACCESS executive secretary, said Dr. Abeyaratne now works hard to provide some kind of care for other HIV and AIDS patients. "To me she is the greatest HIV activist we have ever seen in this region," he said.

The HIV/AIDS rights activist, Rose noted, had rightly questioned the wisdom of having too many AIDS-related non-governmental organisations that do little. "She has challenged us as HIV/AIDS workers and urged us to look at our weaknesses and reconsider priorities and strategies," he said.

Other activists say it was Dr. Abeyaratne who persuaded NGOs to spend more time in the care and support field, leading to the formation of ACCESS. "There is very little or no care and support at all for victims. Most of the work undertaken by NGOs is in AIDS prevention through conferences and workshops," said Rose.

Dr. Abeyaratne, who lives in a posh residential area in Colombo with husband Michael, another well-known paediatric surgeon who gave up private practice after retirement to look after his wife, occasionally travels outstation to address seminars and workshops. She has counselled several HIV/AIDS victims including three women who contracted the virus while working in the Middle East.

The eminent doctor, who worked in British and Saudi hospitals, pioneered research in the anti-malaria field and also on undernutrition, diarrhoeal diseases and patterns of growth in Sri Lankan children. Last month, on International Women's Day, she was presented a special award by the Ministry of women's Affairs for her work in medicine.

A recent ACCESS survey among youth on AIDS awareness found that many teenage children were ignorant about the deadly disease. It found that several students thought the HIV virus was transmitted through mosquitoes, swimming, sharing cups and plates, using the same clothes, handling money, kissing or hugging.

ACCESS, following the success of this survey and a landmark seminar for schoolchildren in Colombo to discuss the dangers of contracting the virus and its prevention, plans to hold many seminars across the island. "We want to hold as many seminars as possible and teach people about the prevention of AIDS in workplaces," she said

Dr. Abeyaratne said they planned to talk to hotel and garment factory workers and educate them on HIV and AIDS. "We also want to do more in the care and support field because that is what is lacking in Sri Lanka."

"What did I feel when I first learnt I was HIV positive? Shock, disbelief, fear, anger, sorrow and finally resignation," she said recalling those first few difficult days after she was told she had contracted the deadly disease.

"But then I thought, maybe talking about it would help me and also others who are suffering from it."

More than the suffering was the unfortunate media publicity and snide remarks from people including colleagues in the medical profession.

"She went through hell in those first few months and people, including some of my colleagues tried to protect the hospital involved in the horrible contaminated blood transfusion saga by saying Kamalika had contracted the virus before," recalled husband Michael.

After an official inquiry found the hospital responsible and on an appeal to President Kumaratunga, Dr. Abeyaratne's expensive drugs are being paid for, from the President's Fund over a five-year period.

"We were on our last legs and would have had to sell our house and other assets to pay for the drugs, when the government agreed to pay for the medicines," said Michael, adding that Kamalika consumes 60,000 to 80,000 rupees worth of infection-preventing drugs per month.

"It is a costly exercise and I know no other HIV/AIDS patient can afford this," she said sadly.

HIV/AIDS social workers said most victims would probably die for want of drugs. "The drugs may be expensive but the main reason I also believe is that victims become depressed, lonely and neglect themselves. They despair and don't seek treatment. They don't want to venture out of their homes," said a social worker.

The government provides AZT only to pregnant women with HIV to ensure the unborn child does not get AIDS. There is no government scheme to help HIV/AIDS victims and patients avoid going to government hospitals because of discrimination by doctors and nurses even though there is a rule that these patients must be treated in any state hospital. Even in hospitals, most doctors and nurses avoid contact with HIV/AIDS patients leaving feeding and toilet care in the hands of relatives or friends. NEST, a non-governmental agency which cares for mental health patients, also works with HIV/AIDS victims, calling over at hospitals under a "buddy" system and talking to patients, feeding and washing them and even taking care of soiled clothes. NEST has also helped to either cremate or bury people who died of AIDS.

When Dr. Abeyaratne declared about three to four years ago, that she was HIV positive, the story made newspaper headlines and shocked people. It was the first time any Sri Lankan had the courage to say he or she was HIV positive.

She concedes, however, that an upper-class background plus the fact that she was infected through a blood transfusion and not sex helped her to go public with her condition.

"I don't think I would have appeared in public saying I am HIV positive if it came from sex," she said. "My husband and family have been very supportive. So have been some of my closest friends."

This doctor who says she misses working with children as a paediatrician, has addressed parliamentarians, journalists, the clergy, judges and schoolteachers since 1997 on HIV and AIDS, often starting her presentation with the words "I am HIV positive".

When she addressed an AIDS conference in South India in 1997, the organizers - learning about her unique Sri Lankan experience - urged her to go public in India too, saying it would stimulate the conference proceedings.

She did so in front of more than 1,000 delegates, many of them non-Indians, and that gave the courage to another Indian woman, having AIDS, to talk about her condition.

Savithri Walatara, a former AIDS rights activist who now works with a UN agency, said Dr. Abeyaratne was let down by the very system she helped foster. "The nurses and doctors who were her students turned against her and refused to touch her when she was found to be HIV positive," Ms. Walatara said, noting that it was unfortunate for a woman who had dedicated her life to medicine.

Another AIDS victim told The Sunday Times that in a class-conscious society, it was difficult for AIDS sufferers particularly in villages to tell even their parents for fear of being chased away or beaten up.

"I know of three young men - in a group of eight AIDS victims whom I met for solace and support - who were asked to leave their homes," said the 30-year-old man who comes from a middle class background.

The man said the hardest part of AIDS is not that it would lead to a slow death but the loneliness. "Death is a natural thing .. you can get hit by a car, you can get a heart attack and so on. No, that is not the problem. For me the loneliness is the hardest part .. the most difficult thing," he said.

![]()

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Plus| Business| Sports| Sports Plus| Mirror Magazine

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to