The Special Report

7th January 2001

India as a safe haven?

A swift deportation

Front Page|

News/Comment|

Plus| Business| Sports|

Mirror Magazine

![]()

India as a safe haven?

V. Suryanarayan

AT long last, the Union Home Ministry acted effectively and expeditiously. In the early hours of December 4, 2000, officials reached M.K. Eelaventhan's residence in Chennai, escorted him to the airport and deported him to Sri Lanka. Eelaventhan, founder leader of the Tamil Eelam Liberation Front, had abused Indian hospitality for long and was championing the cause of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in Tamil Nadu. In fact, quit notices were served on him and another Sri Lankan national, K. Satchida-nandam, six months earlier. However, pressure was brought on the Central government by some of the constituents of the ruling coalition from Tamil Nadu that are well-known LTTE supporters, and the whole process got delayed. This time the entire operation was planned meticulously in order to pre-empt any pressure from pro-LTTE forces in Tamil Nadu and New Delhi.

As

former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi's assassination has started fading away

from public memory, pro-LTTE forces are regrouping and strengthening themselves.

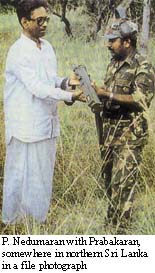

The Tamil National Party (Tamil Desiya Iyakkam) under P. Nedumaran, the

Dravida Kazhagam under K. Veeramani, the Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra

Kazhagam (MDMK) under Vaiko, the Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK) under Dr.

S. Ramdoss and extremist Tamil Nationalist organisations such as the Tamil

National Liberation Army (TNLA) and the Tamil National Retri eval Force

(TNRF) have stepped up their activities. The extremist Tamil organisations

have won over the forest brigand Veerappan to their side. In a strange

twist of fortunes, Veerappan today has become the spokesman of Tamil extremism

and is demanding r edress of the grievances of Tamils.

As

former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi's assassination has started fading away

from public memory, pro-LTTE forces are regrouping and strengthening themselves.

The Tamil National Party (Tamil Desiya Iyakkam) under P. Nedumaran, the

Dravida Kazhagam under K. Veeramani, the Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra

Kazhagam (MDMK) under Vaiko, the Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK) under Dr.

S. Ramdoss and extremist Tamil Nationalist organisations such as the Tamil

National Liberation Army (TNLA) and the Tamil National Retri eval Force

(TNRF) have stepped up their activities. The extremist Tamil organisations

have won over the forest brigand Veerappan to their side. In a strange

twist of fortunes, Veerappan today has become the spokesman of Tamil extremism

and is demanding r edress of the grievances of Tamils.

India's policy towards the ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka has taken a zigzag course, confounding its opponents and supporters alike. One prominent factor that contributed to the failure of the policy has been the absence of a clear-cut objective and a lack of coordination among various agencies involved in the formulation and implementation of policies and programmes. Equally relevant is the competitive nature of Tamil Nadu politics, with the two major Dravidian parties, the ruling Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and the Opposition All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), vying with each other in championing the cause of Tamil militants. V. Prabakaran, the LTTE supremo, exploited these contradictions to his advantage. A few illustrations are given below to substantiate this point.

On August 10, 1983, DMK leaders M. Karunanidhi (now Chief Minister) and K. Anbazhagan (now Education Minister) resigned their seats in the State Assembly as a mark of protest against the "lukewarm" attitude of the Centre towards the "plight of Sri Lankan Tamils" and also as an expression of solidarity with them. The DMK emphatically maintained that the only solution to the ethnic conflict was the creation of a separate state of Tamil Eelam and that a solution cannot be found through mediation. Vaiko, then a DMK Member of Parliament, warned that if India did not send its Army to Sri Lanka, then the "people will march from Tamil Nadu to Sri Lanka". The AIADMK Chief Minister M.G. Ramachandran (MGR), announced that his party would not contest the Assembly seats that fell vacant with the resignation of Karuna-nidhi and Anbazhagan. In order to take the wind out of the DMK's sails, MGR asked his followers to wear black shirts for a month from August 16, 1983. Karunanidhi later became a member of the Upper House, the Tamil Nadu Legislative Council. But MGR was not to be out-manoeuvred. The Tamil Nadu Assembly passed a resolution abolishing the Legislative Council on the plea that it served no useful purpose.

The factional politics in Tamil Nadu had its impact on Sri Lankan Tamil groups. The TULF maintained cordial relations with the Government of India. Its leader A. Amirthalingam wanted to maintain good equations with both the Dravidian parties, but knowing MGR's deep dislike for those associated with Karunanidhi, TULF leaders began to distance themselves from the DMK. The Tamil Eelam Liberation Organisation (TELO), under S.P. Sabaratnam, moved closer to Karunanidhi. Initially MGR was friendly with Uma Maheshwaran of the People's Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE). Uma Maheshwaran however could not retain the friendship for long. Prabakaran stepped into the scene and became very close to MGR, and the relationship continued until MGR's death in December 1987. Prabakaran reaped immense benefits f rom this, not only in terms of money but also by building the LTTE's network throughout the State.

In order to ingratiate himself with MGR, Prabakaran not only distanced himself from the DMK but began to show disrespect to Karunanidhi. In one incident, the followers of the DMK collected contributions from the public on Karunanidhi's birthday in June 1985. Karunanidhi decided to distribute the money among Sri Lankan Tamil militant groups. While TELO, the People's Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE), the EPRLF and EROS gladly accepted the financial gift, Prabakaran declined to accept his share. While Karunanidhi was extremely upset, it had the effect of bringing Prabakaran still closer to MGR.

Gradually the LTTE built its vast network in different parts of Tamil Nadu. Tamil Nadu became not only its sanctuary, but a safe haven from where the Eelam struggle derived political and material support. The LTTE exploited fully the contradictions on the Indian political scene - between the AIADMK and the DMK, between the Union government and the State governments, between the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) and the Indian Peace-Keeping Force (IPKF).

The IPKF's plea to successive governments in Tamil Nadu - during AIADMK and DMK rule and even President's Rule - to curb the activities of the LTTE fell on deaf ears.

The intransigence of the LTTE and its readiness to flout all canons of civilised behaviour became evident in June 1990. In its single-minded pursuit of one-party dominance, the LTTE murdered EPRLF leader E. Padmanabha and his associates in Chennai. The well-knit LTTE network enabled the assassins to escape from the scene of murder without any difficulty.

Even after Padmanabha's assassination, security in the State was not streamlined and tightened. The killing of Rajiv Gandhi in the prime of his life was the culmination of the overt and covert Indian involvement in Sri Lanka and the equally despicable LTTE activities in Tamil Nadu. After the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi and later the publication of the Jain Commission Report, the AIADMK and the DMK made a sudden somersault and each started accusing the other of supporting the Tigers.

The Government of India and the Government of Tamil Nadu must take immediate steps to revamp their security machinery, both on land and at sea. In recent years there have been a number of serious lapses, which enabled the LTTE to become a law unto itself . Very few people are conscious of the fact that six of the accused in the Rajiv Gandhi assassination case - Robert Payas, Jayakumar, Shanti (Jayakumar's wife), Vijayan, Selva Lakshmi (Vijayan's wife) and Bhaskaran (Vijayan's father-in-law) - were registered as refugees. A clear case of abusing Indian hospitality. Kiruban, a top LTTE leader, escaped while being taken to Pudukkottai in April 1993. In May 1993, Charles Nawaz, a witness in the Rajiv Gandhi assassination case, escaped from the Saidapet Special Camp. Cadres of the LTTE enacted a daring escape from the Tipu Mahal camp in Vellore in August 1995. All these incidents reflect poorly on the security machinery.

The unwillingness to take hard decisions has created a number of anomalous situations pertaining to Sri Lankan Tamils. In one instance Special Judge V. Navaneethan awarded capital punishment to all the 26 accused in the Rajiv Gandhi assassi nation case. The Supreme Court confirmed the death sentence on four and awarded life imprisonment for three. The rest were convicted for lesser offences under the Arms Act, the Explosive Substances Act, the Foreigners Act, the Passport Act, and so on. As they had already undergone imprisonment for a period, the Supreme Court set them free. While the acquitted Indian nationals were set free, the Sri Lankan Tamils were lodged in special camps.

The other instance relates to the Ahat case. The ship M.V. Ahat was registered in Singapore and was flying a Honduran flag. It allegedly carried weapons and ammunition for the LTTE in Jaffna when the Indian Navy and the Coast Guard intercepted it. After an exchange of fire, the ship was set ablaze and some Sri Lankan Tamils, including Kittu, committed suicide. Judge Lakshmana Reddy acquitted all the accused in the case and ordered the Commissioner of Police to hand them over to Honduras. The Special Investigation Team (SIT) and the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) went on appeal to the Supreme Court, which found the accused guilty on some charges and sentenced them to a total period of imprisonment of three years. Here again, the accused had already completed the term of imprisonment and, therefore, were set free.

These examples should serve as a warning to New Delhi and Chennai. Even under existing rules and regulations, aliens working against the Indian national interest can be deported. What is lacking is the political will to make difficult decisions. India, especially Tamil Nadu, cannot afford to become a "soft state".

-Frontline

A swift deportation

By T.S. Subramanian

M.K. Eelaventhan, general secretary, Tamil Eelam

Liberation Front (TELF), was deported from Chennai to Sri Lanka on December

4 in a swift operation. Immigration officials and a team of policemen reached

his house at Arumbakkam around 5 a.m. He was driven to the airport and

put on a Sri Lanka Airlines flight, all within a few hours.

A refugee from Sri Lanka, Eelaventhan was overstaying on his visa. And, according to top police officials, he was meddling with the country's internal affairs. Eelaventhan was often seen at news conferences addressed by P. Nedumaran in October and November at the time that the Tamil nationalist leader and firm supporter of the LTTE, undertook two missions to the forests to meet Veerappan to negotiate the release of Kannada film actor Rajkumar whom the forest brigand had abducted on July 30. Eelaventhan reportedly issued press statements supporting the brand of Tamil nationalism professed by Veerappan and Nedumaran. He had also been provocatively flaunting his sympathies for a banned organisation, the LTTE, and its fight for the formation of a Tamil Eelam in Sri Lanka.

The Union Home Ministry has been worried about the emerging nexus involving extremist Tamil nationalist organisations, the Tamil Nadu Liberation Army (TNLA) and the Tamil National Retrieval Force (TNRF) and Veerappan. The TNLA wants Tamil Nadu to secede from the Union of India, and some TNRF cadres were trained by the LTTE in the Tamil areas of Sri Lanka.

With Eelaventhan increasingly seen in the company of Nedumaran, the Centre felt that he was abusing India's hospitality. According to a top police officer, the directive to deport Eelaventhan came from the Government of India. The Immigration Department comes under the Union Home Ministry.

There were advance indications about the Centre's moves. Home Minister L.K. Advani, in a statement in the Rajya Sabha on November 30, said despite the LTTE having been declared an unlawful organisation in May 1992, its activists and sympathisers were indulging in activities in India. The Tamil Nadu government had detained some such activists.

Mainstream political parties in Tamil Nadu have ignored the deportation issue. Neither Vaiko, general secretary of the Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (MDMK), nor Dr. S. Ramdoss, founder, Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK), reacted. Both support the LTT E and the Eelam cause. When the Union government served deportation orders on Eelaventhan and another Sri Lankan Tamil living in Chennai, K. Satchidanandam, earlier this year, Vaiko reportedly took up the matter with the Union Home Ministry.

However, general secretary of the Dravidar Kazhagam K. Veeramani termed the deportation "inhuman". Eelaventhan had came to Tamil Nadu as a refugee along with tens of thousands of other Sri Lankan Tamil refugees. "How will refugees have visas?" Veeramani asked.

Members of the Tamil Sanror Peravai (Tamil Intellectuals' Federation), at a meeting in Salem on December 7, condemned the deportation. Tamil Annal said that Telugus and Kannadigas would not have allowed such a deportation from among them to take place. Eelaventhan was a high-profile Eelam activist. He had been an employee of the Sri Lankan Central Bank and one of the leaders of the moderate TULF but he left that party in the late 1970s to found the TELF (along with Kovai Maheswaran). He reached Tamil Nadu in 1981 after anti-Tamil violence broke out in Sri Lanka.

Although many Eelam activists lay low after Rajiv Gandhi's assassination, Eelaventhan carried on merrily, at times supporting the LTTE but always espousing the Eelam cause. On February 8, 1997, the Q-branch police in Chennai arrested Eelaventhan, K. Satchidanandam, Dr. Malini Rasanayagam, Dr. R.S. Sridhar and an LTTE cadre Pandian alias Muralitharan on charges of conspiring to procure and supply medicines to the LTTE in Sri Lanka. But a court in Chennai acquitted all five in August 1999. Informed sources said the current move against Eelaventhan was "a warning" to other Sri Lankan Tamils not to take for granted the hospitality extended to them by India.

-Frontline

![]()

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Plus| Business| Sports| Mirror Magazine

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to