| The

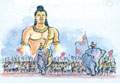

first king of Anuradhapura King Abhaya on the other hand, did not get involved at all. He was silently observing the situation. None of the brothers informed him of what was going on. It was Prince Girikadashiva, who was the most embarrassed. He could neither side with the brothers nor show sympathy towards Pandukabhaya. The hasty action taken by his daughter, brought about this situation. 2 Lake ‘Thimbiriyagana’ was just adjoining Pandukabhaya’s camp at Dumrakgala. There roamed an unusual type of mare, with a white body and feet, golden in colour. She looked very strong and wild and could run as fast as lightening. One of Pandukabhaya’s men, saw this mare and told him about it. Immediately, Pandukabhaya set out, rope in hand.

4 Pandukabhay arrived at the lake immediately, with rope and noose and tried to trap the mare. The mare escaped. The prince gave chase. The mare ran through the length and breadth of Dumrakgala, with the prince following close behind. Then the mare jumped into the river. The prince jumped too. The mare was surprisingly quick even in the water. The prince, who was thoroughly exhausted by this time got furious. He was determined to catch the mare somehow. The mare then stopped.

6 Now, it was Pandukabhaya’s fourth year of stay at Dumrakgala. He got wind of his uncles planning to fight him. He marched forward with his army and camped at Ritigala (Ritigala – then, had been a small town). Except King Abhaya and Prince Girikadashiva, all the other uncles marched to fight him. Severe fighting ensued. Countless were the dead. Victory was for Pandukabhaya. When all the dead bodies were piled up, a commander is said to have commented that it looked like a pile of ‘Labu’ – a kind of pumpkin. That place has been named ‘Labugama’ in later years.

8 Pandukabhaya was crowned the Chief King of Anuradhapura, with Swarnapali as his queen. Chandra became the King’s Chief Advisor (Purohita). Pandukabhaya’s uncle Abhaya was made the ruler for the night, who had to be in charge of the security of the city. This is how the post of ‘Nagara-Guttika’ originated. The King appointed Girikadashiva, the ruler of ‘Galkada-rata’.

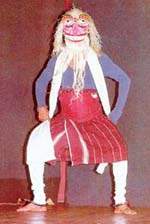

The nadagam form of folk art became popular in modern times when Professor Ediriweera Sarachchandra produced ‘Maname Katava’ (the story of Prince Maname) in the mid fifties using two types of folk plays - the Kavi Nadagama, which, as the name suggests, is entirely in verse, and the Kolam, performed with masks. After nearly fifty years, the play is still being performed. Author Martin Wickramasingha has a lot to say about how a nadagama is performed ,in his novel ‘Ape Game’. The nadagama, according to him, occupied a high position among those amusements, which supplied the villagers with entertainment. He believes that the nadagam came to us from South India and was at first a community festival. “The villagers, big and small assembled and selected the actors necessary to portray each character from among themselves. The heroine was portrayed by a man in female guise. Some of the youths from richer families would bear the expenses of constructing a shed, supplying costumes and training the actors involved. No admission fee was charged for these amateur performances, and even the women of the wealthier families were wont to attend them. It was after

nadagama became professional theatre that women ceased from coming

to see them. At that stage it was professional artistes, who produced

nadagams. Earlier it had always been produced by the leaders of

the village community; a member of one of the leading families in

the village was always chosen to play the king or the hero”. “The hall was sheltered by an octagonal roof like that of the Pattirippuwa. It had a circular platform. There was a small quadrangular shed adjoining it, and the back of this served as a green room, while the front portion formed part of the stage. The orchestra sat on a circular dais at the centre of the platform and made melody with the Tamil drum, cymbals, dola-drum and violin. Their music was more soothing to the ear than the wailing of the seraphina, a hybrid musical instrument introduced by the West perhaps through India”. He goes on to describe the seating arrangements. “The gallery reserved for those patrons who paid five cents was the bare earth, spread with cadjans. It was only the wealthier folk who paid twenty-five cents, who were entitled to chairs. There were very few villagers indeed who had the wealth or the standing to occupy one of the easy chairs, which constituted the ‘box seats’. But it was no rare sight to see a wealthy villager who might have lounged at ease in one of them buying a five-cent ticket to the gallery where he stood leaning against a post or a coconut palm. It is difficult to say whether he did so because he did not see why he should spend fifty cents where five would do or because he feared that stretching out on an easy chair might make him fall asleep before he saw the best part of the play which came after midnight”. How did the play itself proceed? “The play commenced with the entrance of the ‘Reciter’ who took the place of the ‘Sutradara’ in ancient Sanskrit drama. This ‘Reciter’, a man in woman’s clothes, greeted the audience with a song and made his exit. He was followed by two ‘Bahubuthayas’, who wore the conventional costumes of clowns in the English theatre and danced a comic jig. Each actor was heralded by the ‘Pothe Gura’ or Master of Ceremonies, who recited an introductory verse from his book and whistled for each. The clowns, who were skilled dancers trained by the ‘nadagam gura’, sang a song, which was amusing despite its rustic flavour. The ‘Sellan Lama’ or the ‘playful children’ wore velvet trousers and jackets bedizened with bead embroidery and carried a huge graving stylus in one hand and an ola leaf in the other. They danced even better than the ‘Bahubuthayas’ and perhaps bore witness to the choreographic skill of the director, for they danced so long that they even wearied the audience. “After the couple of ‘playful children’ came the Heralds. They danced and sang a song announcing that the king would enter in state. Their exit made way for the entry of the General of the King’s army. Of all the dancers in a nadagam, it was the General who took my fancy most. He leaped on stage, dressed in short trousers and a velvet jacket thick with sprays of bead and tinsel flowers that glittered in the lamplight. As he strode round the stage with his arrogant bearing and martial tread, the white plumes on his head-dress quivered. He thrilled us as he brandished his sword and challenged the enemies of the king to combat. “The exit of the General preceded the entry of the King with the Queen, the Princess and train of courtiers. As the king progressed around the stage, he would pause at certain points and raise the chair-leg transformed into a sceptre by layers of tinsel to the level of his face and slowly move it from left to right. The dances, which began with the entrance of the ‘Reciter’ ended at midnight with the entrance of the King. It was after this that the tale itself was enacted. It was because the staging of the story was preceded on each day by this prologue that it took a fortnight or even as much as a month to complete the dramatised story”. |

||||

Copyright © 2001 Wijeya Newspapers

Ltd. All rights reserved. |

1

Upatissagama underwent a period of unrest due to constant wars.

On one side of the river, Prince Pandukabhaya was strengthening

his armies, with the assistance of Chandra, whilst on the other

side, King Tissa and his brothers were raising armies.

1

Upatissagama underwent a period of unrest due to constant wars.

On one side of the river, Prince Pandukabhaya was strengthening

his armies, with the assistance of Chandra, whilst on the other

side, King Tissa and his brothers were raising armies. 3

The mare was haunting the area near the lake. However much Pandukabhaya

attempted, he was unable to catch the mare. Suddenly it disappeared.

The prince waited long to see the return of the mare but it never

did. So he left a man there, to keep watch and inform him no sooner

the mare reappears. The man kept watch till late evening and saw

the mare appear suddenly. He wasn’t sure from where it appeared.

He ran to the camp to inform the prince.

3

The mare was haunting the area near the lake. However much Pandukabhaya

attempted, he was unable to catch the mare. Suddenly it disappeared.

The prince waited long to see the return of the mare but it never

did. So he left a man there, to keep watch and inform him no sooner

the mare reappears. The man kept watch till late evening and saw

the mare appear suddenly. He wasn’t sure from where it appeared.

He ran to the camp to inform the prince. 5

Pandukabhaya caught the mare and tamed her with difficulty. Then

it was revealed that the mare was none other than a ‘Yakkhini’

– Chetiya by name. According to legend, during King Vijaya’s

time, when the ‘Yakkhas’ were defeated, she had settled

in Dumrakgala. She had been the wife of a powerful ‘Yakkha’

ruler. Whatever that may be, Pandukabhaya was able to return to

his camp, riding on its back.

5

Pandukabhaya caught the mare and tamed her with difficulty. Then

it was revealed that the mare was none other than a ‘Yakkhini’

– Chetiya by name. According to legend, during King Vijaya’s

time, when the ‘Yakkhas’ were defeated, she had settled

in Dumrakgala. She had been the wife of a powerful ‘Yakkha’

ruler. Whatever that may be, Pandukabhaya was able to return to

his camp, riding on its back. 7

After celebrating his victory, Prince Pandukabhaya left the following

day along with his army. Instead of returning to Upatissagama, he

went to meet Prince Anuradha, who happened to be his grandfather.

Anuradha, who was very old then, was overjoyed to see his grandson,

who was able to continue the proud lineage. He embraced the prince.

He handed over the city of Anuradhapura to Pandukabhaya and retired

elsewhere.

7

After celebrating his victory, Prince Pandukabhaya left the following

day along with his army. Instead of returning to Upatissagama, he

went to meet Prince Anuradha, who happened to be his grandfather.

Anuradha, who was very old then, was overjoyed to see his grandson,

who was able to continue the proud lineage. He embraced the prince.

He handed over the city of Anuradhapura to Pandukabhaya and retired

elsewhere. There

were numerous forms of folk drama some of which were confined to

certain areas in the country. For example, Kolam, which is a very

popular form of folk drama in the coastal areas is unknown in the

hill country. Sokari, on the other hand is a type of folk drama,

which is limited to the up country. The Nadagama is a form of folk

opera, which has been popular in the villages along the western

coast from Chilaw right down to Tangalle in the deep south. These

have been generally performed throughout the night.

There

were numerous forms of folk drama some of which were confined to

certain areas in the country. For example, Kolam, which is a very

popular form of folk drama in the coastal areas is unknown in the

hill country. Sokari, on the other hand is a type of folk drama,

which is limited to the up country. The Nadagama is a form of folk

opera, which has been popular in the villages along the western

coast from Chilaw right down to Tangalle in the deep south. These

have been generally performed throughout the night.