Development, democracy and British foreign policy

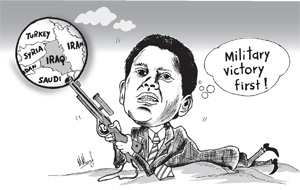

Minister Peiris’s contention was that despite conflicts in most of the countries in our region they had all achieved economic growth. It is an interesting issue for it seems to suggest that economies could grow even under conflict situations and that peace is not essential to achieve economic development. It is in some ways similar to that old debate whether democracy is a sine qua non for economic development as some in the west maintained. But then there was strong economic growth in South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore, all under authoritarian regimes at the time with little signs of the creation of democratic space. The question however is whether the results of such economic growth percolate to the people in general, to the grass roots, or whether they were enjoyed by a coterie at the top of the pyramid. The point that Prof Peiris was trying to make, I guess, was that while growth was possible even under conflict situations, there will not be equitable distribution of the benefits and an inclusiveness that takes in all the people irrespective of where they live, their ethnicity or religious persuasion. In short, only a democratic polity and democratic practice will allow for the benefits of economic growth to percolate vertically as well as spread horizontally so as to reduce the disparities between towns and villages and between regions. That calls for conscious policy decisions and their implementation. His thought makes eminent sense if we look seriously at the problems that Sri Lanka has faced in the last 35 years or more. The first JVP insurrection was also about the lack of economic development in the provinces, the lack of job opportunities even for university graduates mainly because of their lack of proficiency in the English language which they termed “kaduwa”, the weapon that decapitated them and stopped their upward mobility. The Tamil issue is not entirely ethnic though it has been made out to be so. It is also an economic issue, to do with land, employment and a fairer share of the fruits of development. We know growth can be achieved without the mass of the people benefiting from it. Judging by Minister Peiris’s plans, he is trying to bring the benefits to those who produce for export, especially at the regional and sub-regional levels so that there is more equitable distribution of the wealth created, among his other ideas. But if all this is to happen then greater democratization as envisaged in the recent elections in the East, is the necessary first step towards inclusive and equitable development. While not all appear to have been convinced about the government’s plans to settle the conflict, Prof Peiris appears to have left a deep impress among his audience. At a later meeting on climate change organised by the Commonwealth Foundation, some of those who had heard the minister told me that Lord Rogan who had presided at the talk, had congratulated Peiris for speaking for 38 minutes without a single note and for not repeating a single phrase he had used. Not so British foreign secretary Miliband, I am afraid, who spoke from a prepared text which was made available after delivery. I am quoting directly from that text so I cannot be accused of distortion, or even a vendetta against Miliband who I have only seen and missed the opportunity of meeting as I was in the Solomon Islands. In the course of setting out Britain’s foreign policy goals Miliband said: “UK foreign policy will also support the use of the hard power of military force-from Kosovo to Darfur to Afghanistan and Iraq. Military victories never provide solutions, but they can provide the space for political and economic solutions to be found.” If this is British foreign policy, the authorised version as set out by the foreign secretary, why is Sri Lanka being criticised for pursuing a similar, if not the same, policy? What is Miliband in fact saying? He says military victories do not provide solutions. Okay, let’s agree with him for the sake of argument at least. So what do they do? They provide space. Right, space for what? For political and economic solutions. Fine. What and where are the political and economic solutions? They are still to be found. In essence what Miliband means is that while military gains do not provide solutions per se, they provide the opportunity for politico-economic solutions. But these solutions are yet to be found and they have to be found after the military victories. The foreign secretary is not saying that one should aim at military victory and political/economic solutions simultaneously, that there should be a twin-track approach. Oh no. Unless his facility or mine, in the English language has somehow been impaired, there is no sign of ambiguity in what he is saying. Military victory first, political and economic solutions thereafter. It is a linear policy not a parallel one. That is clear enough from the fiasco in Iraq where the British invaded alongside the Americans without a clear strategy on what to do once military victory had been achieved. Britain might have asked the US about an exit strategy but do not seem to have pursued it vigorously enough before joining hands with its transatlantic cousin to invade a sovereign country on a pretext that was later found to be entirely spurious. Afghanistan earlier presented a slightly better picture but even that is coming unstuck. When the UK then preaches to us about presenting political solutions and not to pursue a military campaign, it is being hypocritical to say the least. This is not to say that one needs to totally endorse that policy, but it certainly is intended to expose the sanctimonious humbug the UK preaches to us while announcing to the world its own policy of military victory first, political solutions later. It would seem that what is good for the British goose is not good for the Sri Lankan gander. What is worse is that Sri Lanka has not invaded sovereign nations in the name of some amorphous ideal that was simply meant for the birds while the truth was hidden from its own people and the world. Britain might well say that Sri Lanka is violating human rights and committing serious crimes that remain unsolved or unsolvable for some reason; that it is trampling on civil society unlike them. While a prima facie case might be made for that position, it does not alter the basic premise of the British argument that political and economic solutions to conflicts can be advanced after military victory is achieved and not necessarily before or during, as they would want Sri Lanka to do. Whether such military victories are achievable and sustainable is a different argument. My remarks relate to the British foreign policy goals as stated. There are other observations of Miliband in the report that require comment. But it will have to be on another occasion. |

|

||||||

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Reproduction of articles permitted when used without any alterations to contents and a link to the source page.

|

© Copyright

2008 | Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. All Rights Reserved. |

It was just the other day that I laid my hands on the text of a talk that International Trade Minister GL Peiris gave at the Royal Commonwealth Society in London a couple of weeks ago. I was in Colombo at the time but was back in London just in time for the British government’s launch of its Annual Human Rights Report 2007 and listened to foreign secretary David Miliband explain how central human rights and humanitarian protection are going to be in UK foreign policy. Both were interesting and thought-provoking talks for different reasons. In their different ways they were both dealing, broadly speaking, with conflict and the consequences of such conflict. Prof Peiris’s approach was regional as he was talking of conflict and development in South Asia, whereas Miliband’s was more global because of the UK’s foreign policy goals and what it says are human rights concerns.

It was just the other day that I laid my hands on the text of a talk that International Trade Minister GL Peiris gave at the Royal Commonwealth Society in London a couple of weeks ago. I was in Colombo at the time but was back in London just in time for the British government’s launch of its Annual Human Rights Report 2007 and listened to foreign secretary David Miliband explain how central human rights and humanitarian protection are going to be in UK foreign policy. Both were interesting and thought-provoking talks for different reasons. In their different ways they were both dealing, broadly speaking, with conflict and the consequences of such conflict. Prof Peiris’s approach was regional as he was talking of conflict and development in South Asia, whereas Miliband’s was more global because of the UK’s foreign policy goals and what it says are human rights concerns.