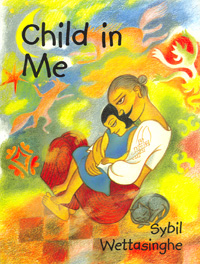

A haven of serenity and exquisite beauty where the daily chores were carried out with love and care and the kind, sensible and eccentric lived in harmony. This intriguing village-Gintota- in the coastal district of Galle is the setting for Sybil Wettasinghe’s celebrated book-Child in Me. The dexterity with which the author captures the vibrancy and essence of village life has enabled many a happy reader to be part of the story. As each page is turned and the story unfolds, the readers find themselves drinking tea at the village kade, sitting at the school close to the sea and enjoying a refreshing bath at the well.

This book which has captured the hearts of children and adults alike not surprisingly won the Gratiaen Prize in 1995. To enable more readers enjoy this book it has been translated into many languages. The Sinhala version of the book which has been re-printed six times is a bestseller. The book was translated into Tamil by Sarojini Devi Arunachalam and was also awarded the State Literary Award. ‘Child in Me’ was translated into Dutch in 1996. So widespread is the fame of this book that it has now been translated into yet another language-Japanese. This book which has captured the hearts of children and adults alike not surprisingly won the Gratiaen Prize in 1995. To enable more readers enjoy this book it has been translated into many languages. The Sinhala version of the book which has been re-printed six times is a bestseller. The book was translated into Tamil by Sarojini Devi Arunachalam and was also awarded the State Literary Award. ‘Child in Me’ was translated into Dutch in 1996. So widespread is the fame of this book that it has now been translated into yet another language-Japanese.

The Japanese translation was accomplished by the Director of the Tokyo Children’s Library, Kyoko Matsuoka who is also a much recognized translator in Japan. Kyoko who is herself an author of children’s books, a former member of the Editorial Board of the Asian Cultural Centre for UNESCO (ACCU) who has produced many useful books for young children was greatly appreciative of ‘Child in Me.’

“What a lovely piece of writing it is!” says Kyoko adding that Sybil is fortunate indeed to have had such “a blessed childhood” which she is able to recall with such stunning accuracy. Sybil has been successful in entertaining children for many years and has been the worthy recipient of many awards for art and literature. Her astonishingly sharp memory recalls every minute detail adding flavour to this account of her childhood in Gintota.

- Shalomi Daniel

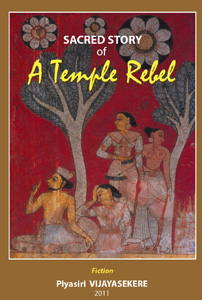

A different, difficult and daring book

This is a daring, different, difficult and challenging piece of writing. It is a biography of a rebel, A Temple Rebel, but in doing so the author is also attempting a socio –political critique of existent institutions, ideologies, social structures, histories and mores of Sri Lanka. The canvas is vast, the themes many, but because the experiences of the protagonist have the first-hand quality of lived experience, the writing acquires a focus and a certain power.

The story’s protagonist is Sinhaputra Aracchilagé Don Vishvasundar, or SAD Vishva. This again is an ironic play on a typical form of ‘nicknaming’ that is very prevalent among Sri Lankans. The name itself positions him in the social context. Similarly the title Sacred Story of A Temple Rebel places it consciously against the Jataka story tradition, as a serious if ironic take off on the Sinhala pansiya panas jataka pota. The book thus begins with a nidhâna katha or ‘Root discourse’ on ‘Why rural youth were reborn as Temple Rebels’; and is divided into three chronicles.

As the author himself claims the “story is titled ‘Sacred’ not because its protagonists have any intrinsic birthright to sanctity or nobility like in the many sacred stories of the Bodhisatta, only their intentions are noble and selfless and therefore sacred: willing to sacrifice their lives ‘for the good of the many’.” This statement positions both the author and the thematic thrust of the book.The hero or protagonist Vishva is portrayed as a modern-day Bodhisattva of sorts. As the author himself claims the “story is titled ‘Sacred’ not because its protagonists have any intrinsic birthright to sanctity or nobility like in the many sacred stories of the Bodhisatta, only their intentions are noble and selfless and therefore sacred: willing to sacrifice their lives ‘for the good of the many’.” This statement positions both the author and the thematic thrust of the book.The hero or protagonist Vishva is portrayed as a modern-day Bodhisattva of sorts.

The first chronicle deals with his arrest, transport to a prison in Jaffna and his experiences there. He sees the shackled escort by airplane with a security detail ironically as being ‘Under Caring custody’. In the detailed, sensitive and powerfully vivid description of prison life, -- the author is able to present a critique of the authority structure, as well as a sympathetic if unvarnished account of the hierarchies that develop within such systems and institutions and the varied personalities that are denizens of such domains. Through all the horrors of incarceration Vishva maintains an uncanny equanimity – bodhisattva-like - in his interactions and relationships with the prison residents. This does not mean however that the criticism of the system is in any way less scathing. In the following passage:

“Vish realizes not just academically but in pure physics of physicality put to test every passing minute inside, how brutally legalized is their rehumanizing prison logic . . . ‘You know why you fellows are sent to his brutish hell? Because you ARE brutes! You asked for it, so we gave. Here we transact in your own currency. . . Brutal? No. Brutocracy! The Rule of Law for the masses of Brutes.’”

What hits the reader from the very beginning of the book is the author’s fascination and almost obsessive play on and with language, language structures and the intentional distortions of such accepted structures. It is as if in an attempt to break out of prison-like boundaries he decides to break free of the grammatical structures of the English language while yet choosing to write in it. The opening lines clearly emphasize this.

“Onceuponatime there was a land of serene serendipity. All subjects and all their communities lived in heavenly harmony and paradisiacal bliss . . . . So narrates the Sacred Stories in canonical history.

--- But why some voices cry high a different story: ‘that all such canonized histories are mere grandiloquent hysteries of Konqueror King Kongs and their dynosaur dynasties. . . that they scribed them to sing (false-)praise of such Dig Vijaya “victories” . . . and, that they only “won” by suppressing Dharmic Battles for Multicultural Identity?” (p.7)

This opening passage establishes the ironic mode in which the story is to be related, the multiple themes of history, war, national and multicultural identities which will be critically examined, and the linguistic aberrations and distortions in which it will be done.At times this constant play on language and image, drawing on a wide ranging background and experience of worlds and cultures works very well. For example in the chapter titled, “The Haute Cuisine of Torture”, the author makes a fine play on his knowledge of the French culinary world, its special dishes, of different meats, condiments and spices, the sophistication of techniques in their preparation, all brilliantly used in extended images of the techniques and types of torture.

“Most loyally the delicate ‘final touches’ of pre-interrogation torture techniques are saved for the Master of Ceremony. At what precise milligram of calibration, with what precise ‘pinch of spice,’ at what precise moment of boiling or roasting and with what other accompanying assortment of ‘secret’ ingredients and conditioning (no, not publicly available from the common culinary recipes) should be there for the final ‘hands-on’ works to commence, is an extremely personal and subtle matter of gourmandise, and therefore a jealously guarded privilege of the Chef.”

After elaborate images describing the different forms of torture in terms of Bouilabaise, Coq au vin, Boeuf Bourguignon and Pot au Feu, the section ends with the following passage:

“Perhaps the most blood curdling moment in this process, Vishva begins to feel, is the agonizingly and calculatively delayed waiting. While waiting for the heralding of the ceremonial buffet, by insidiously and imperceptibly activating their ‘guessing game,’ they allow time to marinate the fine fibres of the suspect’s brain membranes. The waiting hours drag out to be days and weeks. Impossible to recede or recline and unable to proceed or advance the suspect is penalized to be hanging on a threshold of hell.”

Again when his “Hindian philosophy lady professor” advises Vishva to stop involving himself in “running between lawyers and courts and political contact with other suspects,” and concentrate on his academic exams, Vishva answers in brilliant turns and twists of language and images,

“Thanks to the police and the pressure of their roundtheclock vigilance on me, I am forced to ‘proact’ also my modest faculties. I’m made to be faster, and even overcompensatively, also roundtheclock. Now, with my re-energized mental ‘eyes,’ I fleefly my own surveillance, hawkdetect and swoopdeep, twistturn and snatchgrasp the most important ‘catch’ by its finer points -– like a weirdwinged bird unerringly catching its indispensably vital prey, amidst armies of gunrunning homosapiens.”

It is not easy perhaps to sustain the brilliance of this kind of linguistic experimentation over the length of a novel. […] Since the larger themes of the work involve a wide ranging socio political critique -- institutions like the police, the prison system of incarceration, academia, the re- Buddhistizing’ rehabilitation of youthful ‘insurgents’ and a range of other important if tangential issues, such disparities and dissonances are perhaps inevitable.

What is impressive however, in the totality of the book, is the author’s wide ranging academic background, his knowledge of the histories, cultures and societies of the western world that clearly impinge on this work, his lived experiences in those many worlds and at the same time his rootedness in his own language and the world of his native land. The work is daring in its approach to, and critique of, the political status quo. The manner in which the author places and contextualizes that critique by projecting the Temple Rebels from distant rural villages as modern day bodhisattvas who rightly or wrongly sacrificed their lives for the public good; ‘Bahu jana hitâya, bahujana sukâya’, and his use of the Jâtaka story tradition so intrinsic a part of Sinhala culture as a backdrop for his work, gives to the whole work an expansive overarching unity.

The book is structured in three sections or chronicles. The first, titled Under Caring Custody deals with Vishva’s incarceration in Jaffna prison, in solitary confinement, as a dangerous rebel or insurgent. It sets him up as the hero, an intellectual, ex- university student, in an unlikely place, (the Jaffna prison or Yaal Ciracchaalai ) who then becomes a somewhat distanced, ironic, yet compassionate commentator on his surroundings and his companions.

The next chronicle titled ‘Among Divinities in Holy Penitence’ is a vivid recreation of prison activities seen as ‘performative acts’ or rituals. Here the narrative comes alive with a range of characters brilliantly captured and described: The prison poosaari – prisoner turned priest – or ex-school teacher or Vaathiyaar, who ‘is a big massive man in his mid fifties’ who has ‘to bend his tall trunk to enter the lowly portals of his kovil. Before being destined to bend his lofty crown and enter this ‘other’ temple which is Yaal Ciracchaalai’ he was a Brahmin school teacher, a domineering arithmetic master, adept at calculating where and how he can make fat profits, with “a dark skinned miniscule woman with a deformed mouth” as wife, “valued for her sovereign gold and her father’s five acres of cultivated land begifted to him in this land hungry Jaffna peninsula. This god-fearing and much husband-fearing wife each day religiously brings a heavy, double meal container of lunch and dinner by noon.”

The religious ritual Vaathiaar performs for the prisoners and their uncritical subservience is another area where the writer can bring in his social critical comments.

Then there is Pettha, ‘a small quick footed agile man’ officially ‘a double-murderer convict serving his prison sentence for life,’ but ‘bureaucratically his serving has been so exemplary’ that he has been appointed a menial official. His ritual parade as he walks from cell to cell delivering letter to prisoners, as he ‘stops in front of the particular inmate’s cell, makes a robotic turn exactly facing it, heaves his head, straightens up his body, brings his both legs together militaristically, looks straight into the inmate’s eye . . . hands the letter from his left hand and makes a slight majestic donor’s nod,’ is yet another of these prison inmates. Pettha introduces Vish to his tribal world and culture, “ a community of happy, free culture (or ‘Polygamic/Polyandrous’ for those Puritanics) where no man or woman desires to possess or be possessed, with four or five concomitant partners – the unwritten but uquestioningly and abundantly accepted community norm.’

Then there is Cinna Bala of Karai Ur “whose sharply pointed singing voice cuts like a diamond chip, smooth and subterraneous, who reigns ‘uncontested as the Singing Star of this Yaal Sunset Boulevard which opens its flood gates past 5.30 every evening. . . It is the time when ‘Bala and his Night Wailers almost pour out their broken hearts in their nasal sonority, as they pass their fat ganja smokes from one to the other.”

Piyasiri is at his best when he describes these prison characters. It is an insider’s sharply sensitive critical eye and fine irony that evokes them. And there are many such - – a kaleidoscope of personalities and their histories.

The power of this book comes from the fact that it is clearly an autobiography, fictionalized it is true, but the concerns, world view, range and diverse linguistic and intellectual stances are those of the author. It is this intellectual range and wide experience that enables the author to bring into play excerpts from his wide reading, the constant interjection of uncannily apt quotations from the Buddhist Jatakas, the successful experimentation with linguistic structures and multiple vocabularies.

Sometimes they work brilliantly. […] But as I said at the beginning, this is an unusual, different, difficult and daring book that both challenges the reader and the writer. It is the autobiographical dimension that gives both the power to the writing and the pressure for the polemic.

(The writer is a Professor Emerita, South Asian Literature and Culture, Princeton University, USA) |

This book which has captured the hearts of children and adults alike not surprisingly won the Gratiaen Prize in 1995. To enable more readers enjoy this book it has been translated into many languages. The Sinhala version of the book which has been re-printed six times is a bestseller. The book was translated into Tamil by Sarojini Devi Arunachalam and was also awarded the State Literary Award. ‘Child in Me’ was translated into Dutch in 1996. So widespread is the fame of this book that it has now been translated into yet another language-Japanese.

This book which has captured the hearts of children and adults alike not surprisingly won the Gratiaen Prize in 1995. To enable more readers enjoy this book it has been translated into many languages. The Sinhala version of the book which has been re-printed six times is a bestseller. The book was translated into Tamil by Sarojini Devi Arunachalam and was also awarded the State Literary Award. ‘Child in Me’ was translated into Dutch in 1996. So widespread is the fame of this book that it has now been translated into yet another language-Japanese.  As the author himself claims the “story is titled ‘Sacred’ not because its protagonists have any intrinsic birthright to sanctity or nobility like in the many sacred stories of the Bodhisatta, only their intentions are noble and selfless and therefore sacred: willing to sacrifice their lives ‘for the good of the many’.” This statement positions both the author and the thematic thrust of the book.The hero or protagonist Vishva is portrayed as a modern-day Bodhisattva of sorts.

As the author himself claims the “story is titled ‘Sacred’ not because its protagonists have any intrinsic birthright to sanctity or nobility like in the many sacred stories of the Bodhisatta, only their intentions are noble and selfless and therefore sacred: willing to sacrifice their lives ‘for the good of the many’.” This statement positions both the author and the thematic thrust of the book.The hero or protagonist Vishva is portrayed as a modern-day Bodhisattva of sorts.