J.B. Priestley, The writer who spurned Ceylon

The vast majority of the British writers who visited the island during the 20th century were beguiled by the exoticism, inspired by the physical beauty, and intrigued by the society and culture. However, for two writers this was not the case: they had no empathy for the country and could barely abide the experience of their encounters “forty leagues from paradise”. One, as is quite commonly known, was D.H. Lawrence. The other, less-known, was J.B. Priestley, the playwright, novelist, and social activist, whose name is mainly associated with the classic play An Inspector Calls (1945).

Born in Bradford in 1894, John Boynton (“Jack”) Priestley left school at 16 and worked in a wool firm, while at night he began to write newspaper articles. He served in World War One, was wounded by mortar fire, and when peace broke out studied at Trinity Hall, Cambridge. Subsequently he became a novelist, described as a “comic rationalist”. “The contradictions and absurdities of the human situation,” he commented, “could best be borne by a stance of ironic detachment”. His second novel, Benighted (1927), a thriller about travellers stranded in a strange house, was made into a film titled The Old Dark House (1932) by James Whale, director of the iconic Frankenstein (1931). The Good Companions (1929), about the joys and sorrows of members of a repertory company, was awarded the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction, and Angel Pavement (1930) furthered Priestley’s reputation.

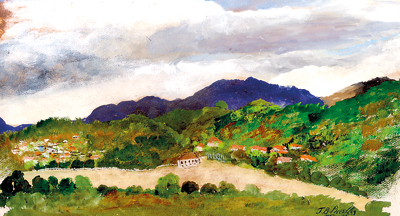

A painting of the Kandy Lake by J.B. Priestley, reproduced here courtesy Ismeth Raheem

Priestley also became a playwright; such an excellent one that he is best-known for his contribution to theatre. His plays are more diverse than his novels and, most particularly, his theatrical devices are often influenced by philosopher J.W. Dunne’s theories of time, such as in Dangerous Corner (1932) – in which, for instance, the disclosure of a group of characters’ secrets is erased when the play returns to its opening at the fall of the curtain – Time and the Conways (1937), I Have Been There Before (1937), Johnson over Jordan (1939) and The Long Mirror (1940).

Of all these ‘time plays’ as they are referred to, the most popular is An Inspector Calls (1945), considered one of the classics of mid-20th century theatre. Set in a small town in 1912, the play opens with the interruption of a dinner party at the home of a factory owner, Arthur Birling, by the arrival of Inspector Goole, who is investigating the suicide of a girl.

As the evening passes he reveals family secrets that implicate each member of the household in the girl’s death. Later, the characters discover the suicide has not yet occurred.

Priestley was a documentary scriptwriter and presenter for the GPO Film Unit, which produced Basil Wright’s The Song of Ceylon (1934). “If you wanted to see what camera and sound could really do, you had to see some little film by the Post Office of the Gas, Light & Coke company,” Priestley remarked.

“Grierson [head of the Film Unit] and his young men, with their easy contempt for big prizes and soft living, their taut social conscience, their rather Marxist sense of the contemporary scene always seemed to me to be a generation ahead of the dramatic film people.”

In Alberto Cavalcanti’s We Live in Two Worlds (1937), Priestley talks to camera about international trade and communications as a benign force, which he contrasts with the military obsessions of individual nations. He also wrote the script for the wartime classic, Britain at Bay (1940), around the time he presented a weekly BBC Radio programme, Postscripts, which quickly became popular: 40% of Britain’s adult population listened in. Graham Greene asserted: “Priestley became after Dunkirk a leader second only in importance to Churchill. And he gave us what other leaders have failed to give us – an ideology.”

Priestley argued in Postscripts: “We cannot go forward and build up this new world order, and this is our war aim, unless we begin to think differently – stop thinking in terms of property and owner and begin thinking in terms of community and nation.” His left-wing sentiments led to Churchill’s Cabinet supplying negative reports on the broadcasts to the Prime Minister. Subsequently the programme was cancelled, but Priestley had influenced the politics of the period and aided the Labour Party to gain a landslide victory in the 1945 General Election.

Priestley co-wrote the feature film The Foreman Went to France (1942), a true story about an aircraft factory worker spirited into France to prevent the Nazis obtaining vital equipment.

Priestley also co-produced and wrote the screenplay for the dark comedy Last Holiday (1950), starring Alec Guinness, about a salesman misdiagnosed as having a terminal disease. Such was Priestley’s versatility that he wrote the libretto for The Olympians (1948), which opened the 1949-50 Covent Garden season, a project with composer and conductor Arthur Bliss.

Priestley’s autobiographical writing is contained in four differing volumes published over a period of 40 years. Midnight on the Desert (1937) concerns ruminations on his character and the hereafter while in a shack on an Arizona ranch. A companion volume, Rain upon Godshill (1939), employs a similar framing device of Priestley, in his study, meditating as a shower falls upon the village of Godshill in the Isle of Wight. “In each of them I began by establishing myself in a certain place, and then proceeded to recall the events, opinions, thoughts, I had known during the previous 12 months.”

Margin Released (1962) contains his literary reminiscences. Lastly, Instead of the Trees: A Final Chapter of Biography (1977), is about his travels, the Ceylon trip being the first described. He was accompanied by his third wife, the archaeologist, writer and filmmaker Jacquetta Hawkes, who, apart from her brilliance was, according to an obituary (The Independent, March 20, 1996), “an outstandingly beautiful and fascinating woman, assisted by her impeccable taste in dress. She presented a cool and rather formal exterior. But there was a suggestion of hidden fires. She had a lovely but ambiguous smile, a kind of Mona Lisa look, which presented men with a challenge.”

The reason for the Ceylon visit is not given by Priestley or Christine Finn in her e-publication A Life on Line: Jacquetta Hawkes (1910-1996) (2005). Nevertheless, Finn writes of the late-1960s: “Jack and Jacquetta were always in demand. British Council lecture tours allowed them plenty of comfortable travel, and Jacquetta continued to record their trips with her camera.” The Jacquetta Hawkes Archive at Bradford University contains “35mm slides of Ceylon (1970?)”. (For the query regarding the year see below.)

It appears reasonable that the Priestleys were invited by the British Council, as had Basil Wright, George Bernard Shaw and Angus Wilson (the latter’s visit coincided with the Priestleys’ and they met accidentally while climbing Sigiriya, which is not mentioned in Instead of the Trees). However, according to British Council records this was not the case, though the couple stayed in Colombo with the then Country Director, Bill McAlpine, and his wife Helen (again not mentioned by Priestley).

When working on Instead of the Trees Priestley realised he’d forgotten the year of their visit, or anywhere else from 1968 onwards, “when after all I was getting on a bit”. He comments, “If any travel record exists, I have never seen it. I know roughly where we went, but not exactly when and in what order. What year, for instance, took us to Ceylon?”

According to biographer Vincent Brome in J.B. Priestley (1988), it was in the playwright’s “seventieth year”, or 1964. However, Neil McAleer in Odyssey: The Authorized Biography of Arthur C. Clarke (1992), states that the Priestleys stayed with Arthur C. Clarke “early in the year” of 1970. McAleer’s estimate certainly corresponds with Priestley’s remark, “It [the visit] was in [the northern] winter of course”.

Proof that McAleer’s date is correct has been provided by several sources, one being Somasiri Devendra, whose father D.T. Devendra was Assistant Commissioner of Archaeology.

Somasiri says his father and Jacquetta were introduced perhaps at a talk the latter gave to the Royal Asiatic Society. Whether D.T. Devendra met Priestley is not known, but at least he got one of the author’s books signed through Hawkes. That book was the novel It’s an Old Country (1967), which quashes Brome’s 1964 theory. As D.T. Devendra was not a great admirer of Priestley, most likely it was a gift: while travelling, most authors take recent publications as gifts.

The timing of the visit, the prevailing conditions, and Priestley’s hatred of Ceylon, are dealt with in a swift paragraph: “I seem to remember it was New Year’s Day shortly after our arrival at our lodgings not far from Kandy. For at least a week, it rained in blanketing torrents, so nothing could be seen, except the colony of little black ants that shared our rooms. (They finally held a mass meeting under my pillow, with delayed delegates hurrying over my face.) Before we flew out there, everybody cried ‘Oh Ceylon! You are so lucky! We were there once and adored it.’ Well, from the first to last, side-trips and all, I hated it.”

There was one particular incident that Priestley describes in which, as his biographer writes, “Barbarism reached unexpected refinement”. Priestley, an enthusiastic painter of landscapes, states, “Even though it was the only country in which I had stones thrown at me by a gang of sullen lads while I painted, I am not prepared to say exactly why I hated it.”

Clues to his hatred are linked to the country’s history: “There was something in the atmosphere of the place that disturbed me, almost as if the abominable cruelties practised in Kandy had poisoned the air.”

This subject had been aired before in a book of short commentaries, Outcries and Asides (1974), published to coincide with Priestley’s 80th birthday: “Ceylon’s history is divided between long peaceful stretches of reservoir building and outbursts of appalling violence and cruelty, and it was as if my unconscious was obscurely aware, on a mysterious wavelength, of these abominable outbursts and their orgies of sadism, and some feeling of revulsion seeped through into consciousness.”

Priestley admits he met “some hospitable people”, but he felt there was about them “a noticeable lack of self-confidence and any suggestion of creative energy. They might have known in advance that the island would run into trouble, as it surely did a few years later.” He did experience some magical moments that characterise the positive aspects of the island, but the negative side always loomed: “There came moments of tranquility and beauty, when for the time being one’s heart and mind were at peace. But these were set against what seemed to me this darkly brooding atmosphere, into which a great deal of hate, both racial and social, had been spilled.”

The stone-throwing “sullen lads” interrupted Priestley’s favourite pasttime, painting. Indeed, it has been suggested that painting was the reason for the visit. His enthusiasm for the artistic experience is evident: “There was an instant magic in handling brushes and paints, matching or contrasting colours, bringing character into design. No wonder – at least in my experience – painters are happier persons than writers.” His attitude to Ceylon was probably further dimmed when he was interviewed by an SLBC presenter who was under the impression he had written E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India (1924)!

What of the paintings Priestley executed in Ceylon? One was a favourite of his. Most of his collection was stored in a cellar, but special canvases adorned his bedroom: “Lake Sevan in Soviet Armenia [Republic of Armenia]; mountain country in County Mayo; moorland in Central Wales; a glimpse of the New England coast; another of Morocco; another of Ceylon . . .” A watercolour of Kandy Lake gifted by Priestley to Bill McAlpine, was later presented to Ismeth Raheem, in whose collection it remains.

While staying near Kandy Priestley frequently walked into town to borrow books (he read until 1 a.m.), “passing on the way groups of Singhalese girls in pretty coloured dresses who might have stepped out of an old-fashioned musical comedy. I found most of the books in the library of the British Council, but now and again I wandered into a much older library, all dust and decay and Edwardian fiction, that was like a crumbling outpost of the old Empire.” This was probably the United Services Library situated within the archaeological heritage of the two-storeyed Queen’s Bathing Pavilion (ulpenge), built over the lake near the Dalada Maligawa.

He seems to have tired of Kandy, judging from a remark, “Oh blessed day!” about a day-trip to Nuwara Eliya. “It was like arriving in the England of 1910. There was a stately club [the Hill Club presumably], where we lunched solemnly and well, and then sat about in 1910, noticing among other things two full-sized billiard tables, which must have taken a little army of men and mules (perhaps even elephants) to hoist them up that steep winding road.”

Priestley, a nationalist as well as socialist, had an imperialist vision at the Hill Club over a cup of Ceylon tea, during which he “saluted the fallen grandeur of the British Empire. But then, by this time, I might have had Rudyard Kipling at my elbow, for I was becoming an imperialist years and years too late.”

He was unconvinced that independence created for the liberated a way of life any better than the imperialist past. “Indeed, I think large numbers of them are worse off than being poorly governed and heavily taxed to support their independence. I not only think so but have been told so by some poor men in various places. ‘Wish the British were back’ they have muttered, well out of hearing of the middle-class intellectuals, the nationalist rebels now in power.

“It was the rise of these types, together with the colour nonsense following the arrival of so many white women, that brought an end to the Empire and little relief and new prosperity to the toiling masses. Not in Ceylon, I admit; but then Ceylon would never have known even its own history if it had not been for the laborious search there by an English civil servant; and I was not surprised to learn later that the island, idiotically governed, was turning into an ugly mess.”

John Boynton (“Jack”) Priestley

It’s a pity he didn’t name the civil servant who provided the Ceylonese with their “own history”. As he probably refers to an English translation of the Mahavamsa the most likely candidate is George Turnour of the Ceylon Civil Service and his The Mahawanso in Roman Characters with the Translation Subjoined, and an Introductory Essay on Pali Buddhistical Literature. Vol. I. (1837). This was the first English translation and printed edition of the Mahavamsa.

The only person Priestley could relate to was fellow-Briton Arthur C. Clarke who he met at Unawatuna in the company of Ismeth Raheem. Priestley described Clarke as “bursting with self-confidence and creative energy and completely unaware of any hostile island atmosphere. Clearly he could live anywhere but had enthusiastically fixed his choice on Ceylon . . . I think he is the happiest writer I have ever met. He lives just where he wants to be; he writes exactly what he wants to write; and he is successful; and I doubt, if a new planet offered itself, he would do more than pay it an exploratory visit.

He is a nice chap and I liked him, and I trust he will not take offence if I suggest he is so happy there in Ceylon because he has the heart and outlook of an enthusiastic boy about 16 (On the return journey Priestley had remarked to Raheem “Well, he’s very sharp and engaging – for a 10-year-old!”). But then his Ceylon is certainly not mine.”

When Clarke’s British publisher decided to issue a collection of short stories in 1972 titled Of Time and Stars: The Worlds of Arthur C. Clarke, Priestley was invited to write the introduction, which he accepted.

Perhaps Priestley was informed that a production of An Inspector Calls had been staged in Colombo. Don Rubin states in The World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre, Vol. 5: Asia/Pacific (1998), “Despite the dominance of film [during the 1950s], western-style plays continued to be produced by such groups as The Thespians, headed by Lucien de Zoysa . . . Even plays by Sartre and J.B. Priestley were produced.”

Jacquetta Hawkes: the archaeologist “with a kind of Mona Lisa look”

Apart from de Zoysa’s production, there was another of significance by the International Theatre Group (ITG) in 1972 performed at the Lionel Wendt Theatre and on tour at Bandarawela, staged at St Thomas’ College hall. The director was Sita Parakrama, the stage manager Andrew David, and the players were Lal Senaratne, Iranganie Goonasinha, Yolande Elias, Osmond Jayaratne (Inspector Goole), Jayanthi Dias Abeysinghe – Jhansi Ponniah on tour – Rohan Ponniah and David Sansoni. Steve de la Zilwa remembers that “the set was an open stage, without walls, dominated by a haunting portrait of Yolande Elias”.

The play was often given a minimalist setting.Apart from Priestley’s observations, the website Celebrating Jacquetta Hawkes reveals the existence of an unpublished article written jointly by husband and wife “about a trip to Ceylon from 1970, [which] gives us a feel for the roles adopted by the Priestleys abroad: Mrs Pro (Jacquetta) revelling in the ‘vegetable sculpture’ of the paddy fields and the ‘huge glistening leaves’ of the jungle, Mr Con (JB) complaining that ‘I’ve seen a fair number of jungles now, and I don’t want any of them’.”

With thanks to Russell Bowden, Andrew David, Steve de la Zilwa, Raja de Silva, Somasiri Devendra, Ranmali Mirchandani, Walter Perera, Rohan Ponniah, Ismeth Raheem, Roland Silva, and David Sansoni.

comments powered by Disqus