Building around an evolving social history

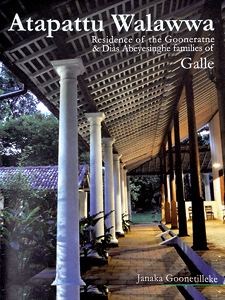

The Atapattu Walawwa is a residential mansion situated on the south western coast of Sri Lanka, in the city of Galle, built in a vernacular manorial Sri Lankan style with an admixture of European colonial elements. It was commissioned in the late eighteenth century and almost doubled in size during the early nineteenth century.

The owners were part of the traditional Sri Lankan elite of the landlord-official class and considered themselves the equivalent of the feudal nobility in the Kandyan kingdom which, however, was not conquered until 1815. Thus, the maritime landlord class was decidedly more westernized, having advanced under Dutch and Portuguese occupation since the sixteenth century.

The house, its surroundings and occupants, have a richly documented history over a period of more than two centuries, capable of being further researched.

The production of the book was an extended family project. It is edited by Janaka Goonetilleke, married to the current owner of the property Darshani Dias Abeyesinghe. The book is descriptive and informative and presented as a preliminary documentation of a multi-faceted historical complex that embodies aspects of social and material life in provincial urban Sri Lanka. It is profusely illustrated with colour photographs, reproductions and drawings.

The early chapters, constituting the bulk of the book, set out the location, layout and stylistic and material aspects of the building, gardens and other appurtenances. These chapters appear to be the result of a collaboration between the editor and two cousins of the owner, Senake Bandaranayake and Susil Sirivardana. They are followed by a single chapter on twentieth century domestic life. It is noted that during the early part of the last century, the large upper storey was strictly restricted to women. The gendered space poses the fascinating question of whether it derived from indigenous practice, or a reordering of indigenous morals according to Christian morality within colonial power relations.

The real social history begins with a chapter entitled Social Background. However, the story recounted in the chapter concerns events in the late nineteenth century, almost 50 years after the building took its nearly final shape. Therefore, it is not possible to really understand how the architectural spaces evolved in response to social need at the time of construction. What we have to imagine is how they might have served the ‘many splendoured life’ of E.R. Gooneratne, described as a gentleman scholar of the Sri Lankan Renaissance. Gooneratne was born in 1845, in Colombo, and baptized in the Wolvendahl Church. He was an Atapattu Mudaliyar, a position held by the family for five generations, and Mudaliyar of the Governor’s Gate; the highest domestic echelon of the colonial state which meant easy access to the colonial hierarchy. In addition, he was involved in road building in the Galle area. Since no details are supplied, one wonders at the landed wealth and other resources that were required to build and sustain the lifestyles of such complexes. The walawwa was a hub for villagers and lesser officials and the Sangha. It was also the centre for official business and interaction.

The large east wing adjacent to the dining room, built in the classical style, is the only addition attributed to the late nineteenth century. It is tempting to ask whether it was a response to the increased official entertainment resulting from Governor Arthur Gordon’s policy to enhance the privileges of the Mudaliyar class. Gordon was convinced that to produce the kind of native official the British wanted, the native gentlemen should be treated precisely like Englishmen in the same circumstances.

Gooneratne converted to Buddhism in 1874 and put himself under the tutelage of the eminent scholar monk Hikkaduwe Sri Sumangala, principal of the Vidyodaya Pirivena, at Colombo. The bond between the two led him to expand his interest in Buddhism and become a patron of the Buddhist revival. The new interests brought him into contact with other intellectuals of the day such as Ananda Coomaraswamy. He had a well stocked library of manuscripts and texts in Sinhala, Pali and English and maintained an office which transcribed, translated and edited classical texts. But the library building in the complex was built earlier, to serve his ancestors. Gooneratne travelled in India, Thailand and Japan, as an unofficial ambassador of Buddhism, and to share the cultural legacy of these regions. He collaborated with Pali scholar T.W. Rhys Davids, founder of the Pali Text Society. The two met when Rhys Davids was a young civil servant in Galle in 1882. Furthermore, Gooneratne had a hand in restoring the damaged Buddha statue and bo madura at the Sri Mahabodhi in Anuradhapura.

Gooneratne’s story, simultaneously a colonial official wearing a western style jacket over a cloth, short hair, a beard and moustache and a Buddhist intellectual, captures the cultural cross currents of the nationalist struggle and animates the dry bricks and stones of a lovely old walawwa complex. His daughter’s wedding photograph reveals women wearing western dress, whereas another image shows the next generation in sari. The complexities of revival in nationalist cultural production are hardly researched. Nevertheless, the shifting dress codes connect the house and its occupants to wider debates that address the general contradictions of the nationalist discourse which simultaneously rejects and accepts the dominance of the epistemic and moral framework of European thought.

The social history of the building ties its architectural forms and spaces into international and national networks of anti-colonial activities not really anticipated at the time of building. Because none of this can be read simply from plans or photographs, the book’s attempt to give physical shape to the unknown social world of a wealthy late nineteenth century nationalist intellectual makes for interesting reading. The editor notes that one purpose of his essay is to encourage young researchers to study Gooneratne and his times in greater depth. Gooneratne’s extensive original diaries are available in the National Archives Department. Chapter numbers, a list of illustrations and an index are absent in this publication. Their omission, however, does little to diminish the appeal of a book which clearly derives from a desire to put people into buildings and read architecture as part of wider social processes.

Atapattu Walawwa is now available at a pre-publication price of Rs. 4,000. For inquiries, email jangoonetilleke@googlemail.com

comments powered by Disqus