Of men of yore and a stately home

Old houses hold stories and when a house has been home to six generations of a family, there is a wealth of such stories told and retold. Stories entwined and enmeshed with the lives of its inhabitants.

Dr. Janaka Goonetilleke

If recent months have seen much excitement over Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations, consider then this picture of another British Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. Queen Victoria was the reigning monarch and Ceylon if not the jewel in the crown, very much a part of the British Empire. The scene is a Buckingham Palace tea party and in the group from Ceylon are Panabokke Dissava, Nugawela R.M., Kobbekaduwa R.M, all three resplendent in Kandyan regalia, Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan, debonair in turban, the demure saree-clad Lady Ramanathan by his side and the imposing figure of E.R. Gooneratne in coat and cloth among the British gentlemen in top hat and tails.

Edmund Rowland Gooneratne was Atapattu Mudaliyar of Galle and also Mudaliyar of the Governor’s Gate, the former a post held by members of the family for five generations, thus bestowing the name Atapattu Walawwa on the family home. Known as a Renaissance Man – scholar, writer, intellectual, social worker and Buddhist nationalist, E.R. was a visionary, his legacy still talked of with awe. Born a Christian, he became a Buddhist later on, deeply committed to the nationalist cause, moving freely with not just the British rulers but an active spearhead of the Buddhist revival through his close association with Ven. Hikkaduwe Sumangala Thera, Colonel Henry Steele Olcott, T.W. Rhys Davids, founder of the Pali Text Society and his enduring links with Thai and Japanese monks.

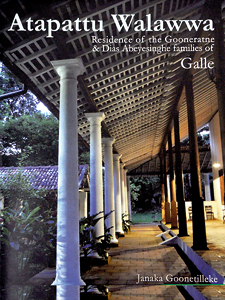

Atapattu Walawwa, the Gooneratne family home is today a protected monument. Built by E.R’s grandfather Don Bastian Gooneratne, and subsequently added to in its over 200-year existence, its story, has now been brought out with the publication of a coffee table book to be launched this week.

The book is the work of Dr. Janaka Goonetilleke who has spent most of his professional life as a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist in the UK, returning frequently these past few years to undertake the restoration of this stately home. Married to a great grand-daughter of E.R and present owner of the house, Dharshani Dias Abeyesinghe, Dr. Goonetilleke confesses to an increasing fascination with not just its history but the way in which it was built in harmony with its surroundings using the traditional wisdom and materials that have withstood the ravages of time and man over two centuries. Helped by Dr. Senake Bandaranayake who had a visual impression of the house as it was before, he began removing everything that was alien to it, trying to get it back to its earlier form.

The dining room as it was in years gone by: The dining table with the pankha and the mural on the far wall. Pix by Indika Handuwala

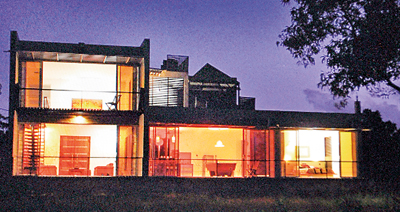

Situated on Lower Dickson Road, Galle, an obviously desirable residential address, Atapattu Walawwa has been built to minimize climatic stresses, facing the southeast so as to make optimal use of the southeasterly winds blowing in from the Indian Ocean. Entering the compound is a step into a more gracious age; the sprawling ‘forest’ garden filled with trees and herbs, catering to the needs of the household, the house itself restored yet redolent of the past.

The colonnaded double front verandah (one of five in the house), Dr. Goonetilleke explains had a purpose; the higher one closer to the house used for welcoming peers while the lower, a later addition would be where visitors of lesser rank would stop. The verandah pillars, pictured on the cover of the book, are a dramatic contrast, neo-classical masonry columns outside and timber pillars within, the latter made of a single block of wood, the former influenced by Western architecture. The rectangular fanlight above the main entrance to the house has the letters DBG in curving letters- a tribute to its builder.

The massive arch which dominates the main hall too speaks of the European influence of the time. Old family photographs dot the walls, among them one of a wedding cake, made for E.R’s grand-daughter Dora Tagora’s marriage to Will Dias Abeyesinghe showing a structure rising almost to the height of the arch. The family’s antique furniture – made predominantly of jakwood also merits a chapter in the book.

The hall has the formal sitting room (sale or salava) and the second hall (the barande) which was the family’s own private space. A feature here is the wooden screen with its beautifully carved panels. From the barande one moves into the central courtyard, the meda midhula, which the family calls the vattarama. The western wing had the residential rooms and to the rear were the kitchens, the main kitchen and another – the exclusive preserve of women. Leading off from the right of the barande is the dining room, where the pankha used in olden days to fan the guests still hangs over the table. A remarkably well preserved mural of the flags of the Kandyan court is on the far wall. Above the dining hall were the women’s bedrooms.

Interestingly, set apart from the main house but connected by a walkway (the last major addition to the house) is ‘the library’, its origin still somewhat a mystery. Much care has gone into its restoration including the uncovering of its distinctive double staircase. The book describes it as “a beautiful example of traditional Sri Lankan street architecture with upper storey wooden balconies on either side and ‘wing’ staircases at the back facing the main house”.

What emerged in the course of his research into the house has Dr. Goonetilleke, totally in awe of the homespun wisdom of the Sinhalese builders of yore, from the ventilation, flooring, walls and roof construction. The walls are made of a mixture of ant hill clay, sand, lime and small pieces of rubble or decayed coral, says Dr. Goonetilleke who can expand at length on the benefits of this building material and its superiority to modern materials such as cement. Ant hill clay because of its porous nature acts as a kind of natural airconditioner, he says, absorbing moisture when it is cold and expelling it when it is hot. Despite their porosity, the walls are strong and the lime used as a binder safeguards it from termite attack, the bane of most building constructions. The roof of Atapattu walawwa has the ‘familiar beam and rafter technique’ covered with semi-circular tiles reflecting the heat.

There is much more to the book than its title indicates for it encompasses not just the architecture and history of Atapattu walawwa but also the social milieu in which the family lived. In order to enter the public service for under the British only Christians could hold public office, the men were brought up in the Christian faith while the womenfolk largely remained Buddhist. The initial chapters focus on the house, its setting, architecture, the technology used in its construction etc but arguably of equal or more interest are the later chapters which give the reader a glimpse of the daily life in the walawwa in the times of Eva Tagora, daughter of E.R. who presided over it for four decades and the social background of the Gooneratne and Dias Abeyesinghe families, described as “ members of a relatively clearly defined social group a palantiya or peruva, an endogamous sub-caste of about fifteen or twenty families which married almost always within its kin.” It goes on to say that ‘this cluster of intermarrying families seems to have formed the uppermost rank of the landlord- official class of the southern and western southern maritime region under Dutch and British colonial occupation.’ Their lifestyle as depicted in the book is an intriguing blend of local and Western- their food, dress, influences all reflecting the hybrid culture of the day, influenced by both East and West.

Representing Ceylon: E.R. Gooneratne, fourth from right, at the Buckingham Palace garden party for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee

Indeed the chapter on E.R reveals this dichotomy and his ‘many-splendoured life’ touched on under the headings ‘the official’, ‘the international traveller’, ‘patron of Buddhist revival’ – Atapattu walawwa being the setting for his activities, obviously could be the subject of another book as indicated in the few extracts from his writings published in the book. E.R, whom Dr. Goonetilleke feels a great affinity with, died in 1914 and his grave is in the family burial grounds within the premises.

The book has been a family effort and Dr. Goonetilleke recalls how gatherings of the clan in 2007, led to a fruitful collaboration. Two of Eva Tagora’s eminent grandchildren, Dr. Senake Bandaranayake and Susil Sirivardana, contributed generously to the text, the delicate line drawings were executed by Thushan Illeperuma and the photographs were by Malaka Weligodapola. For Dr. Goonetilleke personally, producing the book has brought him back to his roots and obviously been an enriching experience. “I’m probably living in the past,” he quips. It’s a past we could learn ample lessons from, he believes and through the book if people could understand this, he feels his efforts would have been well served.

‘Atapattu Walawwa-Residence of the Gooneratne and Dias Abeyesinghe families of Galle’ will be launched on August 3 at the Barefoot Gallery. Former Director of Archaeology Dr. Roland Silva

will be the chief guest.