The house Geoffrey Bawa composed for music lovers

Bastille was the name we gave a certain formidable structure that came up in the neighbourhood in the early Sixties. Looking like the gateway to a fortress or a castle, it brooded over a corner section of Alfred House Road. We liked the nod to medieval Europe, but were not sure if we liked the structure. The “Bastille”, it turned out, was the entrance to the Colombo office of Mr. Geoffrey Bawa, the much talked about architect, who was then in his early forties and gaining stature with each highly original home or building he designed.

Geoffrey Bawa (23 July 1919-27 May 2003). Portrait by Dominic Sansoni / Three Blind Men (copyright)

- Geoffrey Bawa (23 July 1919-27 May 2003). Portrait by Dominic Sansoni / Three Blind Men (copyright)

When we saw Mr. Bawa for the first time — a dauntingly larger-than-life figure who appeared giant-like to 12-year-olds, the “Bastille” made sense; it was the awe-inspiring frontage of a setting in which an awe-inspiring mind was conceptualising awe-inspiring architectural structures such as grand houses, hotels, schools, factories, campuses, Parliament complexes.

Geoffrey Bawa seemed to be known to everyone we knew. He was a year junior to Father at Royal College, Colombo, and his family had close ties with great-aunts and great-uncles over on this side.

Father and Geoffrey Bawa were both in England as undergraduates during the War years. One summer afternoon, in 1942 or ’43, Father was seated in a restaurant near Piccadilly Circus when he saw a tall familiar figure, wavy blond locks and fulsome looks, crossing the street. It was Geoffrey Bawa. He was about to step outside and hail his fellow alumnus when he changed his mind. What caused the change of mind is not clear, but from a description of the non-encounter it would appear that one had decided the two had nothing in common, apart from being ex-Royalist-Oxbridge Ceylonese far from home. The young Bawa, we suspect, probably looked too much the Cambridge University Aesthete for Father’s sober tastes. The two young men might have enjoyed a short chat, but the moment came and went and nothing happened. That was the last time Father saw Geoffrey Bawa.

Mother, on the other hand, would frequently meet Geoffrey Bawa in the harmonious setting of the Colombo music circle. The architect, a connoisseur of the arts, was a loyal patron of symphony concerts and chamber music recitals in the ’60s, ’70s and early ’80s. Dressed in black from collar to toecap, he dominated gatherings at the Lionel Wendt Memorial Theatre and the Ladies’ College Hall, gazing over heads through black-framed glasses and looking more impressive than any ambassador or chief guest. It was as a VIP – Very Imposing Person – that we remember him.

At post-concert parties, held usually at Dr. Earle de Fonseka’s Elibank Road residence, Geoffrey Bawa would go up to Mother and ask her to sing his favourite song, “Blue Moon”, which happened to be her favourite song. Next to playing classical violin, Mother loved playing the role of chanteuse, and singing was how she relaxed after playing in a concert. She would stand by the piano and in a rich contralto sing favourites from the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s. The 1935 Rodgers & Hart ballad was the hit of the evening, invariably.

Around 1962, pianist and string player Carmel Raffel and husband Chris asked Geoffrey Bawa to design a house for them. They had bought a piece of land in a leafy nook in Ward Place, Colombo 7, and they wanted a house that reflected Mrs. Raffel’s passion for music.

Over the next two years Mother would bring from her weekly chamber music practice sessions with the Philharmonia Players updates on the Raffel house. Geoffrey Bawa was putting heart and soul into the project. He visited daily and spent hours at the site, consuming litres of tea, smoking cigarettes by the pack, and reviewing, revising, and sometimes even undoing, the previous day’s work.

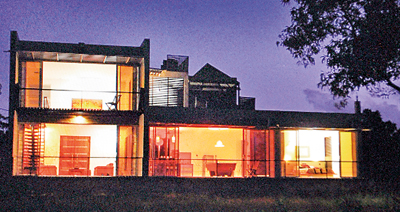

When the house was nearing completion, Mrs. Raffel took us on a guided tour. The entrance was a deep archway that cosily contained a study with a lattice window; polished coconut tree trunk columns were balanced on the indigenous “wangediya”; the wooden-floored hall opened on a high-walled garden sprouting recently planted grass; the stairs led up to a row of high-ceilinged bedrooms, and more stairs to an open-air tower that gave a 360-degree view of the city of Colombo. It was a fairytale of a house.

When the house was ready, in 1964, Mrs. Raffel held a grand house-warming in the form of a chamber music concert. The musicians were members of the Philharmonia Players and the guest artist was Peter Cooper, the New Zealand-born concert pianist. Everyone who was anyone in the local music and arts scene was on the guest list. We arrived early and genial Mama Raffel, Dr. Chris Raffel’s mother, insisted on putting Younger Brother and self in the front row, alongside her grandchildren Adam, Suhanya and Lahiru.

Taking their places around us were the French, German and Italian Ambassadors and their wives; the British Council country director Bill McAlpine and wife Helen; Miriam de Saram (mother of cellist Rohan and pianist Druvi); scholar and arts connoisseur Leonard van Geyzel; music critic Elmer de Haan; theatre couple Iranganie and Winston Serasinghe; soprano Lorraine Forbes-Abeysekera; artist-entrepreneur Barbara Sansoni (in black-and-white cloth and jacket) with older son Simon; artist-musician Sita Joseph-de Saram, husband Sooty and children Jetsun and Rohan (two future concert artists), and so on and on. The rows of chairs in the hall and the medha midhula filled up fast. The air reverberated with a sense of occasion.

Clockwise from top: Members of the Philharmonia Players rehearsing in Mrs. Raffel’s home, circa 1972 (from left - Ajit Abeysekera, Eileen Prins, Evangeline de Fonseka, Carmel Raffel and Wendy Jackson-Miller; detail from score of the Cesar Franck Piano Quintet;

Chalk-white walls with book-lined alcoves made up three sides of the wooden-floored hall, in the middle of which gleamed a Steinway concert grand, grouped with chairs and music stands for four players. A George Keyt oil painting (peasant girl embracing white hen) glowed in the background. Sitting to a side, head and shoulders above everyone else, was the architect Geoffrey Bawa. In a sense, it was his evening.

After the Philharmonia Players had performed a Beethoven string quartet, they were joined by the pianist. What followed was the magnificent César Franck Piano Quintet in F minor. An impassioned, monumental work, towering in structure and gorgeously textured, the quintet carries intensely expressive melodic lines from the strings, buttressed by power-packed chords from the piano. All five instruments propel the music forward with a force that just about shatters the traditional piano quintet mould. It was a total artistic experience, the music celebrating the setting, the setting exalting the music. Years later, recalling that resplendent evening, we feel a deep gratitude to everyone involved that night, the musicians, the hosts, the guests, and the man who built the house.

During the post-concert party, the adults milled around with wineglasses in their hands, pausing by trays of cocktails and amuse-bouches as they went about examining and exploring the new Bawa creation. The junior audience members sat in corners or ran around with fistfuls of devilled cashewnuts.

As we weaved our way among the guests we suddenly looked up into the face of Geoffrey Bawa. He was dressed in midnight black, sipping a glass of red wine and gazing on the glittering scene. In a lordly, undemonstrative way, he looked a pleased man.

For a fraction of a second his gaze met ours. He must have known why we were staring. One of the lenses in his eyeglasses was cracked. Like a flawed windowpane, a vertical line of fracture ran down the middle of the left lens. We veered off into the crowd, not wanting to embarrass the great man with our stare. As a myopic schoolgoer who had often suffered the humiliation of cracked or smashed spectacles, we empathised with Mr. Bawa who, we presumed, must have dropped his glasses that day.

A week after the Raffel house concert, Mother, Younger Brother and self were emerging from a taxi outside the Savoy Cinema in Wellawatte when we saw Geoffrey Bawa stepping out of a Rolls-Royce. The first thing we noticed was the cracked lens. In those pre-courier service days, when the only opticians around were Eric Rajapakse and Albert Edirisinghe, it took 10 days to get a new pair of glasses. We knew what Mr. Bawa was going through.

The film we had come to see was the comedy-thriller “Topkapi”, with Peter Ustinov and Melina Mercouri. As we were leaving the theatre we saw Mr. Bawa, towering over the exit crowd, looking around for his car, a hint of a smile on his impressive face.

Over the years, and always from a distance, we would glimpse Mr. Bawa at one music and art function or another. The last glimpse we had was in 2003, at the Barefoot Gallery. He was in a wheelchair. He had come to see an exhibition of paintings and sketches done by an English artist living in Sri Lanka.

The subject of the exhibition was Geoffrey Bawa; all the portraits on display were of the architect. He was said to be in poor health. Eminently dignified even in a wheelchair, he gazed musingly at those who had come to see him and the versions of him in mixed media. It was not long after that Geoffrey Bawa passed away.

Architectural drawing of Dr. Chris and Carmel Raffel’s home.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Carmel Raffel continued to do what she most loved doing, getting together with her musician friends and hosting soirees. Ten years after they had settled in the Bawa home, the Raffel family sold the house and moved to Australia.

Over the past several nights we have been listening to the César Franck Piano Quintet, played by pianist Sviatoslav Richter and the Borodin String Quartet. We listen with the full score, la grande partition, open on our lap. As the music unfolds we turn the pages, matching piano, violin, viola and cello parts with the faces of those who performed this same quintet one memorable evening in 1964. With each hearing, that house concert comes alive. And the house that Geoffrey Bawa designed is a solid part of the music and the memory.

comments powered by Disqus