Sunday Times 2

Julian Assange asylum: Ecuador is right to stand up to the US

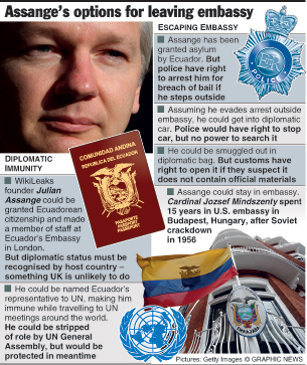

Ecuador has now made its decision: to grant political asylum to Julian Assange. This comes in the wake of an incident that should dispel remaining doubts about the motives behind the UK/Swedish attempts to extradite WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. On Wednesday, the UK government made an unprecedented threat to invade Ecuador’s embassy if Assange is not handed over. Such an assault would be so extreme in violating international law and diplomatic conventions that it is difficult to even find an example of a democratic government even making such a threat, let alone carrying it out.

Ecuador's President Rafael Correa gestures during an interview in Loja. ‘Correa made this decision because it was the only ethical thing to do'. Reuters

When Ecuadorian foreign minister Ricardo Patiņo, in an angry and defiant response, released the written threats to the public, the UK government tried to backtrack and say it wasn’t a threat to invade the embassy (which is another country’s sovereign territory). But what else can we possibly make of this wording from a letter delivered by a British official?

“You need to be aware that there is a legal base in the UK, the Diplomatic and Consular Premises Act 1987, that would allow us to take actions in order to arrest Mr Assange in the current premises of the embassy. We sincerely hope that we do not reach that point, but if you are not capable of resolving this matter of Mr Assange’s presence in your premises, this is an open option for us.”

Is there anyone in their right mind who believes that the UK government would make such an unprecedented threat if this were just about an ordinary foreign citizen wanted for questioning – not criminal charges or a trial – by a foreign government?

Ecuador’s decision to grant political asylum to Assange was both predictable and reasonable. But it is also a ground-breaking case that has considerable historic significance.

First, the merits of the case: Assange clearly has a well-founded fear of persecution if he were to be extradited to Sweden. It is pretty much acknowledged that he would be immediately thrown in jail. Since he is not charged with any crime, and the Swedish government has no legitimate reason to bring him to Sweden, this by itself is a form of persecution.

We can infer that the Swedes have no legitimate reason for the extradition, since they were repeatedly offered the opportunity to question him in the UK, but rejected it, and have also refused to even put forth a reason for this refusal. A few weeks ago the Ecuadorian government offered to allow Assange to be questioned in its London embassy, where Assange has been residing since 19 June, but the Swedish government refused – again without offering a reason. This was an act of bad faith in the negotiating process that has taken place between governments to resolve the situation.

Former Stockholm chief district prosecutor Sven-Erik Alhem also made it clear that the Swedish government had no legitimate reason to seek Assange’s extradition when he testified that the decision of the Swedish government to extradite Assange is “unreasonable and unprofessional, as well as unfair and disproportionate”, because he could be easily questioned in the UK.

But, most importantly, the government of Ecuador agreed with Assange that he had a reasonable fear of a second extradition to the United States, and persecution here for his activities as a journalist. The evidence for this was strong. Some examples: an ongoing investigation of Assange and WikiLeaks in the US; evidence that an indictment had already been prepared; statements by important public officials such as Democratic senator Diane Feinstein that he should be prosecuted for espionage, which carries a potential death penalty or life imprisonment.

Why is this case so significant? It is probably the first time that a citizen fleeing political persecution by the US has been granted political asylum by a democratic government seeking to uphold international human rights conventions. This is a pretty big deal, because for more than 60 years the US has portrayed itself as a proponent of human rights internationally – especially during the cold war. And many people have sought and received asylum in the US.

The idea of the US government as a human rights defender, which was believed mostly in the US and allied countries, was premised on a disregard for the human rights of the victims of US wars and foreign policy, such as the 3 million Vietnamese or more than one million Iraqis who were killed, and millions of others displaced, wounded, or abused because of US actions. That idea – that the US should be judged only on what it does within its borders – is losing support as the world grows more multipolar economically and politically, Washington loses power and influence, and its wars, invasions, and occupations are seen by fewer people as legitimate.

At the same time, over the past decade, the US’s own human rights situation has deteriorated. Of course prior to the civil rights legislation of the 1960s, millions of African-Americans in the southern states didn’t have the right to vote, and lacked other civil rights – and the consequent international embarrassment was part of what allowed the civil rights movement to succeed. But at least by the end of that decade, the US could be seen as a positive example internally in terms of the rule of law, due process and the protection of civil rights and liberties.

Today, the US claims the legal right to indefinitely detain its citizens; the president can order the assassination of a citizen without so much as even a hearing; the government can spy on its citizens without a court order; and its officials are immune from prosecution for war crimes. It doesn’t help that the US has less than 5% of the world’s population but almost a quarter of its prison inmates, many of them victims of a “war on drugs” that is rapidly losing legitimacy in the rest of the world. Assange’s successful pursuit of asylum from the US is another blow to Washington’s international reputation. At the same time, it shows how important it is to have democratic governments that are independent of the US and – unlike Sweden and the UK – will not collaborate in the persecution of a journalist for the sake of expediency. Hopefully other governments will let the UK know that threats to invade another country’s embassy put them outside the bounds of law-abiding nations.

It is interesting to watch pro-Washington journalists and their sources look for self-serving reasons that they can attribute to the government of Ecuador for granting asylum. Correa wants to portray himself as a champion of free speech, they say; or he wants to strike a blow to the US, or put himself forward as an international leader. But this is ridiculous.

Correa didn’t want this mess and it has been a lose-lose situation for him from the beginning. He has suffered increased tension with three countries that are diplomatically important to Ecuador – the US, UK and Sweden. The US is Ecuador’s largest trading partner and has several times threatened to cut off trade preferences that support thousands of Ecuadorian jobs. And since most of the major international media has been hostile to Assange from the beginning, they have used the asylum request to attack Ecuador, accusing the government of a “crackdown” on the media at home. As I have noted elsewhere, this is a gross exaggeration and misrepresentation of Ecuador, which has an uncensored media that is mostly opposed to the government. And for most of the world, these misleading news reports are all that they will hear or read about Ecuador for a long time.

Correa made this decision because it was the only ethical thing to do. And any of the independent, democratic governments of South America would have done the same. If only the world’s biggest media organisations had the same ethics and commitment to freedom of speech and the press.

Now we will see if the UK government will respect international law and human rights conventions and allow Assange safe passage to Ecuador.

Courtesy guardian.co.uk

comments powered by Disqus