Sunday Times 2

A lifeline for Asia’s boat people

CANBERRA – Sometimes countries arrive at good policy only after exhausting all available alternatives. So it has been with Australia’s belated embrace this month, after years of political wrangling, of a new “hard-headed but not hard-hearted” approach to handling seaborne asylum seekers.

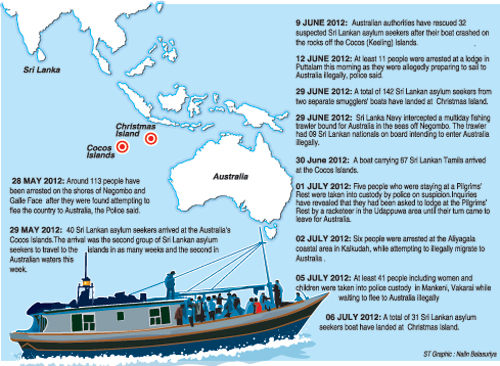

The core of the problem – and what has made it an international issue rather than just a domestic Australian problem – is that the would-be refugees (mainly from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Iran, and Sri Lanka) have been dying in harrowing numbers. In the last three years alone, more than 600 men, women, and children have drowned – and these are just the documented cases – while attempting the long and hazardous journey to Australian shores in often-ramshackle boats run by smugglers operating from Southeast Asia.

The overall number of unauthorised sea arrivals – more than 7,000 a year – remains small relative to other target destinations; the annual figure for such arrivals in Europe from North Africa is close to 60,000. And overall asylum claims made by those reaching Australia by any route are only a small fraction of the number that Europe, the United States, and Canada face every year.

But the moral, legal, and diplomatic issues that arise in confronting Australia’s irregular migration problem are as complex – and the domestic politics as toxic – as anywhere else. So how Australia’s government handles these challenges is being closely watched. Internationally, Australia long had a well-earned reputation for decency on refugee issues. It accepted 135,000 Vietnamese refugees in the 1970s – a much higher total on a per capita basis than any other country, including the US – and ever since has maintained its status as one of the top two or three recipient countries for resettlement generally. But huge damage was done in 2001, when then-Prime Minister John Howard’s government refused to allow the Norwegian freighter MV Tampa, carrying 438 rescued Afghans from a distressed fishing vessel, to enter Australian waters. As a former foreign minister, based at the time in Europe, I never felt more ashamed of my country.

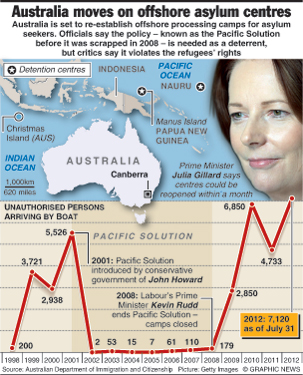

Unfortunately, hard hearts proved to make for good domestic politics. “Turning back the boats,” the “Pacific solution” of offshore processing in neighboring Nauru and Papua New Guinea (PNG), and draconian conditions for those who are allowed to stay pending status determination were – and are – popular positions for Australia’s conservative parties to take.

By contrast, the Labour Party’s reversal of these policies after 2007, for the best of humanitarian reasons, was seen as offering softheaded encouragement to “queue jumpers.”

This perceived weakness is a key explanation for why former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd (much admired by G-20 and other world leaders) was overthrown by his Labour Party colleagues, and why his successor, Julia Gillard (whose government is much admired for its economic management), remains deeply unpopular.

With a flood of recent boat arrivals, fear of more drownings, and national politics becoming even more of a blood sport than usual, Australia’s government finally found a circuit-breaker: a report by a panel of experts comprising a former defence chief, a foreign affairs department head, and a refugee advocate. The panel recommended a new, fully integrated policy package aimed at reducing both “push” and “pull” factors driving refugee flows, and its report enabled government and opposition to find some common ground at last.

Incentives to make regular migration pathways work better will include immediately increasing Australia’s annual humanitarian intake, and doubling it over five years (to 27,000), while also doubling financial support for regional immigration capacity-building. At the same time, asylum seekers will be specifically deterred from making dangerous sea voyages by getting no advantage from doing so: they will, at least pending the negotiation of better Southeast Asian regional arrangements, be sent to Nauru or PNG to wait their turn there.

Effective regional cooperation – to ensure that processing, and settlement or return, is orderly and fast-moving – will be crucial to the package’s long-term success. That means putting flesh on the bones of the Bali Process cooperation framework, which was agreed in 2011 by ministers representing all of the relevant source, transit, and target countries in the region and beyond, including – crucially – Indonesia and Malaysia (the key transit countries en route to Australia).

Whether parties to the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees or not, these states agreed to work with each other and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees on all of the key issues. They will seek to eliminate people smuggling; give asylum seekers access to consistent assessment processes and arrangements (which might include regional processing centers); find durable settlement solutions for those granted refugee status; and provide properly for the return to their home countries of those found not to need protection.

Professional sceptics in Australia have argued that it is inconceivable that any of our Southeast Asian neighbours, including Indonesia and Malaysia, would stir themselves to help solve Australia’s refugee problem, even with Australia’s government covering most of the costs. But the Bali Process ministers have already agreed that this is everyone’s problem, not just Australia’s.

The sceptics also ignore the reality that no government will want to put its international reputation at risk – as Australia did with the Tampa affair – by being indifferent to the horrifying toll of deaths at sea. And they completely dismiss the instinct of common humanity that does prevail when policymakers are given, as they have been now, a practical, affordable, and morally coherent strategy for avoiding further terrible human tragedy.

Gareth Evans was Australia’s Foreign Minister from 1988 to 1996, and President of the International Crisis Group from 2000 to 2009. He is Chancellor of the Australian National University.Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2012. Exclusive to the

Sunday Times

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus