Columns

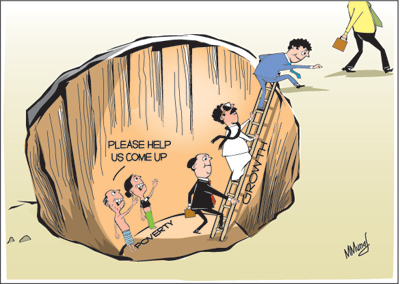

People left behind: How inclusive is inclusive growth?

Poverty amidst growth is a much debated issue these days. The poverty paradigm has shifted from poverty reduction to inclusive growth as the process of rapid economic growth has left out large numbers of people from meaningful participation in their societies. Inclusive growth is concerned not merely with income inequality, but all dimensions of poverty and embraces both income and non-income dimensions of well-being.

ADB perspective

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) contends that over the past decade, Asian countries have successfully reduced income-based poverty and improved living standards for all, including the poor, and those vulnerable to poverty, but large numbers of people are being left behind or left out of economic benefits and access to social services. The ADB says: “Based on most recent international poverty figures, by 2005 about 27% of the Asia-Pacific populations live on less than US$ 1.25 per person a day and 54% are vulnerable to poverty (US$ 2). Despite the global financial crisis, the poverty incidence in the region has further declined over the last years. The social indicators of poverty in the region, as expressed in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) have also shown substantial improvement since the 1990s.”

Nevertheless, the ADB goes on to say: “While poverty and living standards have improved in the region, more than 900 million people in Asia and the Pacific still live on less than $1.25 a day. In terms of economic benefits and access to social services, large numbers of people are being left behind or left out. In many developing countries, economic inequality has increased in the past decade. Without steps to address these disparities, the risks this trend poses – including social instability – will continue to grow.”

New paradigm

This then is the rationale behind the new paradigm of inclusive growth that emphasises that the process of rapid economic growth should not leave out large numbers of people from meaningful participation in economic, social and political life in their societies. Increasing economic inequality has gone in tandem with economic growth in Sri Lanka and other South Asian countries.

CEPA forum

It is in this background that the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) organised an interactive informal first forum under the CEPA Café Series on “How Inclusive is Inclusive Growth?” The well attended forum elicited divergent ideas on the causes for the persistence of poverty and the needed directions in reducing poverty.

Professor Jock Stirrat, an independent consultant and Sussex University Research Fellow, who led the discussion pointed out that the term inclusive growth first appeared in India’s 11th five-year plan which targeted “not just faster growth but also inclusive growth, that is, a growth process which yields broad-based benefits and ensures equality of opportunity for all”. Since then, the precise meaning of inclusive growth has continued to be unclear while the most explicit statements of what is involved in achieving inclusive growth are somewhat worrying. The World Bank points out that the ‘equity’ and ‘inclusiveness’ which the concept appears to promise relates to opportunities and not outcomes. He pointed out that a survey of ADB publications reveals three varying definitions or approaches to the term: declining inequality, pro-poor investments in social opportunities and equal opportunities and equal access.

Shifts in international thinking

There have also been shifts in international thinking from poverty reduction to inclusive growth. Some international organisations emphasise poverty reduction rather than income distribution and accept less egalitarian income distribution if the levels of absolute poverty are reduced. It is the absolute poverty rather than relative poverty that matters in much of current thinking.

Yet different institutions are for poverty reduction, inclusiveness, equity, opportunities or outcomes.

The thrust in development thinking that opportunities not outcomes are what matters in poverty reduction programmes is interesting. In this approach what is needed to produce an equitable society is the equalisation of opportunities: the creation of ‘level playing fields’. Impliedly outcomes would be different, but the equity argument is that opportunities should be the ones that are equal. A contrary view is that opportunities and outcomes cannot easily be separated.

Persistence of poverty

The discussion that followed ranged over many issues on poverty that is of national relevance. It was pointed out that this discussion on inclusive growth is very much the same as the earlier debate on why poverty persists. The main reason for the persistence of poverty was the skewed distribution of assets and capabilities. Unequal assets, wealth and opportunities in turn breed inequalities. Inadequate opportunities lead to inadequate incomes.

Education expenditure

Sri Lanka has improved income distribution owing to its past welfare programmes of free health and free education. Free education is an intergenerational lever to reduce poverty. Many have moved upward socially and economically owing to education facilities provided by the state. It is of current interest that the university academic strike has highlighted the need for higher investment in education that would make society more egalitarian. Public expenditure on education had fallen to 1.47 per cent of GDP, the lowest in many years. This reduction in educational expenditure could be a setback to social mobility. Reduced expenditure on public health facilities too could deprive the poor of good health.

Priorities

Government priorities determined the allocation of expenditure on various sectors. When governments spend large amounts of money on defence, then there are inadequate funds for social welfare policies that are egalitarian in their outcomes. It was pointed out that defence expenditure had a component of egalitarian income distribution, as the bulk of soldiers came from poor rural households. The large amount of defence expenditure on wages would have improved incomes and livelihoods of rural households in particular.

Distributive policies

One of the main reasons for unequal distribution of incomes, it was suggested, was inadequate measures for asset, wealth and income distribution. Current economic thinking and policies were biased towards economic growth rather than distributive justice. In earlier decades economic policies had measures to ensure distribution of wealth and incomes. Taxation measures were oriented towards improved distribution of incomes in the short and long runs. These are now considered counterproductive for economic growth. Improvements in incomes are expected from rapid economic growth.

This strategy has heightened inequality in income and wealth, even though there has been an improvement in poverty. There is dissatisfaction in the extent of prevalence of poverty in the midst of huge wealth accumulation and conspicuous spending by the rich.

Redistributive policies like land reforms enabled improved income and asset distribution in East Asia. One of the reasons for a more egalitarian income distribution with growth there was a mix of economic policies, such that there were policies that benefitted the poor and the less advantaged too. The redistribution of assets is an essential strategy when there is a skewed property and asset structure. Policies that benefit rural areas and agricultural development benefit the poor directly as these improvements enhance the entitlements of the rural poor.

Winding up

Rapid economic growth and diversification of economies alleviate poverty over the long run. However economic and social policies that benefit the poor and integrate them into the economic growth process are needed to ensure inclusive growth. The rhetoric of alleviating poverty must be backed by effective economic and social policies that provide opportunities for economic and social integration and minimise the number of people left behind.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus