A Russian émigré’s canvas in Ceylon

In 1897, the French impressionist Camille Pissaro painted the “Boulevard Montmartre at Night”, highly regarded for its depiction of nightlights illumining the receding Parisian street. There’s another remarkably Pissaro-influenced painting of a street at night time, appearing this time in pre-independence Ceylon painted by the Russian émigré artist, Alexander Sofronoff.

Sofronoff’s work in Ceylon was recently discovered by Shevanthie Goonesekera, quite by chance.

Shevanthie Goonesekera

A Briton with Sri Lankan roots, she came across Sofronoff during a discussion with an old lady recalling her memories of the Galle Face Hotel. While talking about people who stayed there about 70 years ago, the lady happened to mention a Russian artist she remembered as a child. The story instantly fascinated Ms. Goonesekera, a writer, art historian and an artist herself. What was a Russian artist doing in Sri Lanka at that time anyway?

About a year later, she came across one of Sofronoff’s paintings at an auction in Newcastle, England. The auction house had the description of the painting wrong, the date was wrong and even the name of the artist was wrong. But Ms. Goonesekera “instinctively” knew that this was a painting by that Russian artist.

“It was a painting of Ella Gap drawn in the 1940s,” she said. “The auction house was calling it ‘tea country’. Ella Gap is one of my favourite places and just coming across this painting, in terms of all its details, I thought ‘wow’. Really, this painting just inspired me to find out more about the artist.”

Ms. Goonesekera started with a blank sheet of paper with no information. Then, gradually, she met people in England who had more paintings by Sofronoff and various anecdotes about the artist.

“Most British people I came across initially, many of their fathers had been working in Ceylon at the time and they were growing up as children,” she said. “Either they could recall Sofronoff as a child, experiences of meeting him, being painted by him, or recall what their parents spoke of him. It was very valuable information, sort of oral history. A lot of those stories are quite vivid and it just brings the artist to life.”

A rare find at an auction in Newcastle, England: Sofronoff’s painting of the Ella Gap

Sofronoff was born in 1901, east of the Ural Mountains that separates Europe from Asia. He had a sophisticated education in art and he was skilled in creating grand theatrical set designs. In 1917, when the Russian Revolution broke out, Sofronoff, being a “White” anti-Bolshevik Russian, had to flee the country. In 1922, at the age of 21, he set off on a 17-day journey on the Trans Siberian railway to Harbin, Manchuria. In 1931, the Imperial Japanese Army invaded Harbin and Sofronoff fled to Shanghai. As the Second Sino-Japanese war heated up, Sofronoff had to flee again, arriving by sea in Ceylon in 1936. Goonesekera says Sofronoff walked the “dark road” of a refugee, making reference to poetess Anna Akhmatova’s words; “A refugee has to walk a dark road. And foreign bread has a bitter flavour.”

After his arduous journey, Sofronoff seemed to have found his place on the island, deciding to stay here with permanent employment at the Galle Face Hotel as décor artiste. He was quite well off with a monthly salary of Rs. 350, quite a generous amount at the time. He was popular among the British community here, who purchased his art and had him do portraits. Ms. Goonesekera located one of the children Sofronoff drew, Mary Rose, now an older woman in England, who recalled being “awfully bored” by the whole ordeal and wondering how the artist could see through his thick glasses anyway.

Sofronoff made his living by his brush, painting scenes from all over the island and selling them at exhibitions (one painting he even sold for Rs. 400, a price above his monthly salary, Ms. Goonesekera says.) Landscapes were his forte, and the paintings Ms. Goonesekera has recovered show Hill Country scenes, southern scenes, the temples Lankathilaka, Abbhayagiriya and even the Pettah market. She’s still trying to discover more paintings he did, especially the jungle scenes, as a “visual record”.

The Russian émigré’s work in Ceylon of dirt roads and bullock carts is worlds apart from his theatrical designs of ballet dancers and orthodox churches. He had an affinity for colours and light, notably painting shadows in colour, breaking away from the traditional greyish shadow. He was one of the few who drew at night.

“You don’t find many painters painting at night, but it was one of Sofronoff’s strong fascinations,” Ms. Goonesekera said. “He captured the night-time scenes perfectly, all simple lights and kerosene lamps. The only artist who did that was Pissarro the French impressionist who painted that famous night-time scene in Paris.”

Sofronoff had a distinct way of looking at the Ceylon landscape different from the traditional realism portrayed by Lankan painters at the time. Artists capture landscapes in different ways, and for Sofronoff, Ms. Goonesekera says it was about his life experiences, his journey embedded in the long-winding roads of his paintings.

“There must have been something about the landscape and the people that somehow he felt this is the place to stay,” she said.

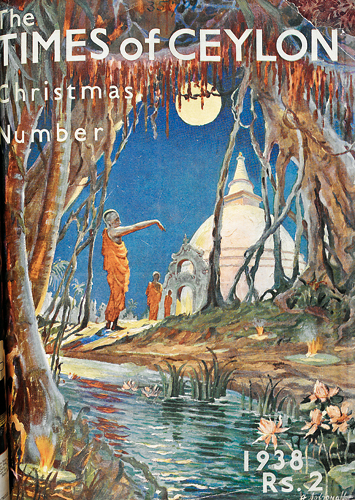

Ms. Goonesekera thinks Sofronoff’s connection to the island might have transcended to a spiritual one from the way he drew temples. Once for a “Times of Ceylon” Christmas edition cover, Sofronoff drew a romantic scene of a temple on a full moon night, lotuses blooming in a lake, a stupa in the background and a young monk trying to catch the moonlight in his arms, titled ‘A fantasy of Ceylon’.

“When I look at other artists of the time, you might see landscapes, people but never really temples,” Ms. Goonesekera said. “How many non-Sri Lankan artists would have felt at peace painting something like a dagoba? That’s why I thought he had an extraordinary connection to the island.”

Sofronoff stayed here until his death in 1947 from a heart attack, most likely triggered by his beloved vodka. But his presence on the island remains through the local artists he influenced, namely Donald Ramanayake, the celebrated landscape painter. Mr. Ramanayake was a student of Sofronoff’s when he was 20 years old, and there’s an impressionist style in Ramanayake influenced by Sofronoff, Ms. Goonesekera said. Mr. Ramanayaka then influenced Ivor Baptiste and Terry de Niese keeping that style alive.

“It’s incredible how one person can influence another and how that influence continues,” Ms. Goonesekera said. “I think what Sofronoff has left is a legacy and a visual record of scenes we can no longer capture. And my journey now is to try and find many of those paintings as possible.”

‘A fantasy of Ceylon’: Sofronoff’s extraordinary connection with the island

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus