News

If it isn’t home it’s a camp by another name

= Find themselves in limbo in ‘no man’s land’

Widow Chandran Selvarani, 48, one of the last inmates of the Menik Farm in Chettikulam, Vavuniya, was told she would be leaving to her own village in Mullaitivu. After living for almost four-and-a-half years in camps for the displaced, she was more than happy to return to her village, Koppapilavu, over 10 km from Mullaitivu town.

The remaining inmates at Menik farm left their ‘home’ of four years with great hope but what awaited them as they disembarked the buses was a far cry from ‘home’. Pix by Priyantha Hewage

Selvarani had lost her husband and two children in the conflict, and was returning home with her son. Her two daughters had left the camp earlier and settled down after marriage. The two children lost during the war, were killed in a shell attack, when they were fleeing the fighting, while her husband who was injured in the same incident, succumbed to his injuries eight months later.

“We were assured by officials we could return to our own village. Even the name of the village which we are returning was displayed on the bus. Therefore, we were happy to leave the camp,” she told the Sunday Times.

“On arrival, we were taken to a school at Vattarapallai in Mullaitivu, which is about three km away from the original location where we were living. We have been told that due to security reasons, we cannot return to the village, as an army camp has been established in the area where we lived,” she said.

She claimed they had six acres of land which they were cultivating before they were displaced. “However, now we have been given about 40 perches of barren land on which we cannot cultivate,” she lamented.She was among 110 families comprising 346 persons, who were moved out from Menik Farm which was shut down this week after almost four years in existence.

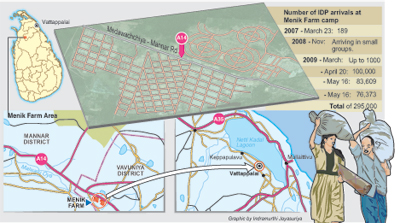

The 6,200-acre land consisting of a former privately owned farm, as well as State-owned, was hurriedly turned into a mass camp for displaced persons, as the conflict reached its peak and thousands were being displaced.

Some 295,000 persons were accommodated in the camp from areas where military operations were conducted in the north.

The majority of the persons have been resettled in their villages or nearby areas. Others have travelled to other parts of the country or migrated.

Though the closure of Menik Farm has been welcomed by many of its former inmates, the haste with which it was carried out, without preparations for the inmates to start life anew, has disturbed many. “After moving from camp-to-camp over the past few years, again we have ended up in a location similar to a camp, without basic facilities”, said a returnee who wished to remain anonymous.

Sivabalan Nirmaladevi, 28, a mother of two from Koppapilavu, another returnee told the Sunday Times, “We have been located in an area where there is no drinking water or basic facilities.”“We were given 15 kg rice, one tin of fish, five kg flour, 1 kg each of sugar and dhal and a packet of milkfood. We are not sure whether we will be given any other relief”.

“We were promised Rs. 25,000 to put up a temporary house, but nothing has been given to us so far,” she said.

Returnees were seen putting up their own temporary homes with roofing sheets, timber and other material they had brought along with them from Menik Farm.

Koppapilavu: From one makeshift home in Menik Farm to another. Pix by Jude Nimalan

One of their main concerns is the lack of opportunities to make a living.“At Menik farm, we were able to do menial labour and earn at least Rs 500 per day, but here, we have no such option, because this is a barren land. Even to go lagoon fishing, we have to travel five km”, returnee S. Chanmugam, a former inland fishermen said.

“As the land does not belong to us, there is insecurity. If we are told to move away, we will have to obey the orders,” he said.

A cross section of the returnees were of the opinion that no major initiative has been undertaken to arrange for a meaningful resettlement. None of the non-governmental organisations had come forward to help them, they claimed.

But, Mullaitivu Government Agent N. Vedanayagam countering the returnees’ claims, said that they were able to provide the basics for them, and would be building permanent houses for them soon.

“They cannot compromise national security and hence, we could not settle them in their original villages,” he said.

“Those involved in inland fishing will be given the opportunity to do so,” he said. The United Nations (UN) on Tuesday welcomed Menik Farm’s closure and called government measures to resettle the last batch of IDPs, a milestone.

“This is a milestone event towards ending a chapter of displacement in Sri Lanka, some three years after the civil war ended in May 2009. But there are still some people who are unable to return to their homes, and a solution urgently needs to be found,” the UN Humanitarian Coordinator in Sri Lanka, Subinay Nandy said in a statement.

The UN, however, said, it is concerned about the 110 families returning from Menik Farm to Koppapilavu in the Mullaitivu District, who are unable to return to their homes which are occupied by the military.”Instead, they are being relocated on State land where they await formal confirmation of the outcome of their land, and compensation if they cannot return,” the statement said.

“The closure of the camp is a significant sign of the transition from conflict to sustainable peace, and the commitment of the Government to resettle tens of thousands of people in their homes,” the UNHC said.”But, there are many people still living with friends and relatives or in welfare centers, particularly in Jaffna and Vavuniya. Some of these people have been displaced for years, and they too need a lasting solution,” he said.

“Allowing returnees to settle anywhere in the country and resolving legal ownership of the land on which they have resettled, away from their original homes, is a key part of the reconciliation process, ” he said.

|

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus