Early movies filmed in Ceylon

By Richard Boyle

The first use of Ceylon as the location for a fiction film rather than a documentary was in 1925 when Englishman Henry Edwards – a forgotten but highly creative director of the silent era – made the 50-minute One Colombo Night (aka Colombo Night). It was produced by Stroll Picture Productions of London, which made a number of documentaries and features between 1924 and 1933.

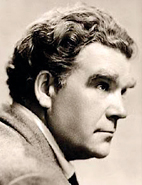

The romantic lead, Nils Asther, with Greta Garbo

I have not seen One Colombo Night, which was released in February 1926, but according to the British Film Institute (BFI) – it has no images, video or articles pertaining to the film – the genre is “Imperialism/Romance”.

The script is an adaptation by Alicia Ramsey of a story by Austin Philips, seemingly unpublished, “About a ruined coffee planter who makes good in Australia and returns to Ceylon to save his fiance from entering a nunnery”. The main actors were Godfrey Tearle, Marjorie Hume and Nora Swinburne. All were experienced and notable performers and later adapted to the sound era with some success – Tearle appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (1935); Swinburne played the lead role in Jean Renoir’s The River (1951).

The supporting cast included the accomplished James Carew, J. Fisher White, Annie Esmond and Julie Suedo, accompanied by Dawson Millward, William Pardue and Grace Lane.

So this first fiction film was appropriately set in Ceylon, as were the subsequent two. But that was not to be the long-term trend, as the island has been mostly used over the past 60 years as an ideal substitute for similar locations in the Asia–Pacific region, and servicing these productions has become a major industry.

That the storyline is linked to the crash of the coffee industry makes it the first example of the Ceylon plantation drama concept in film, but not literature, for that honour lies with William Knighton’s Forest life in Ceylon (1854). Later examples include the film Tea Leaves in the Wind (1938), Robert Standish’s novel Elephant Walk (1948) and its 1954 film adaptation, and the novels Bitter Berry (1957) by Christine Wilson, Dangerous Inheritance (1965) by Dennis Wheatley, The Flower Boy (1999) by Karen Roberts, and The Suicide Club (2010) by Herman Gunaratne.

Director Henry Edwards, who was also an actor and married to Chrissie White, the blue-eyed star of early British cinema, made 69 films including The Amazing Quest of Mr. Ernest Bliss (1920), which is missing from the British Film Institute’s National Archives and is listed as one of the Institute’s “75 most wanted lost films”. The experimental Lily of the Alley (1924) – fortunately not lost – was the first silent film to dispense with inter-titles (the printed text edited into the photographed action to convey dialogue or narrative) and is therefore regarded as significant in cinema history.

It’s satisfying that the first fiction film made in Ceylon was by such an accomplished and pioneering director, described by Bryony Dixon in BFI Screenonline as having “proved himself one of the industry’s most enlightened and important filmmakers, helping to advance British cinema beyond its early concentration on physical action towards the subtleties of characterisation, feeling, and visual design required for the mature feature film”.

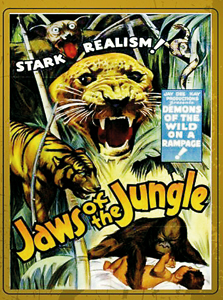

The next film, made in 1935 after the advent of sound cinema and released in April 1936, was the 60-minute Jaws of the Jungle, (aka Jungle Virgin in the US), made by the Hollywood-based but low-budget orientated Jay-Dee-Kay Productions (JDK being the initials of the company’s president and main producer, JD Kendis). The story centres on a village and the attempt by its inhabitants to cope with “swarms of vicious vampire bats” as they make a dangerous journey to obtain a blessing for a marriage between two villagers. Complications develop when the bride’s former suitor’s jealousy results in him attacking the groom.

Tellingly, it was the only film directed by the horror-inspired Hollywood scriptwriter (The Amazing Exploits of the Clutching Hand, etc.), Eddie Granemann. The cast comprised Teeto as “the boy”, Minta “the girl”, Gukar “the rejected suitor” – their sole screen appearance – and Walla “the chimpanzee” and Agena “the honey bear”, all but the chimpanzee and perhaps the bear being of local origin.

The typecast villain, Gibson Gowland, who acted in Tea Leaves in the Wind

While the film used raw talent, there were some experienced individuals associated with the production such as the producer, JD Kendis, who had a penchant for exploitation flicks such as Polygamy (1936), Slaves in Bondage (1937) – promoted as “A Labyrinth of Prostitution and Lust” – Secrets of a Model (1940), Escort Girl (1941), and Youth Aflame (1944). In Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!: A History of Exploitation Movies (1999), Eric Schaefer writes that Kendis “apparently received capital from a relative who worked for MGM”. Furthermore, the music score was written by Johnny Lange, a hit songwriter (“Mule Train”, “Clancy Lowered the Boom”) who contributed to eighty-five films, and the similarly-prolific Lew Porter, both of whom worked in collaboration.

With Granemann as writer and director and Kendis as producer it’s not surprising that this film is startlingly exploitative: “Primitive Life in an Enchanted Land where Savage Killers Roam” the distributor’s advert proclaimed. “Stark Realism” and “Demons of the Wild on a Rampage!” the poster screamed. The savage killers were flying foxes (Pteropus giganteus) as they are known to naturalists, the largest of bats having a wingspan up to 1.5m. Transformed by Granemann from innocent fruit-eaters into vicious vampire bats (there’s a scene in which one kills a peacock), they drive villagers into the depths of the jungle where they encounter every potentially dangerous animal imaginable.

Considering the history of the inter-title, it’s curious that Jaws of the Jungle begins with an extremely long, rolling example, termed by the director “Foreword”:

“Centuries ago the island of Ceylon was densely-populated by a highly civilized people, who erected splendid temples to pagan gods, built great cities and royal palaces, spanned mighty rivers with wide stone bridges and skillfully turned the courses of mighty rivers with aqueducts and canals. Today Ceylon’s ancient cities and palaces are but scattered ruins; its bridges, aqueducts and canals lie buried in swamp and jungle; the countless millions who once inhabited this emerald jewel of the Indian Ocean have vanished. What became of these ancient people of Ceylon? What black tragedy swept them away? Will the few million peaceful humans living in this equatorial Garden of Eden fall victims to the blight that drove the former dwellers of Ceylon out of their island Paradise? WILL HISTORY REPEAT ITSELF? Following is a pictorial account of how the simple people of one Ceylon village eluded a winged pestilence by an epic flight into an undiscovered valley deep in the island’s unknown interior, thereby foiling the initial onslaught of a merciless enemy which might have again depopulated this shimmering green gem of the faraway Oriental seas.”

Thus Granemann, having acknowledged the early architectural and hydraulic achievements, proceeds to distort history by suggesting that a “winged pestilence” drove the population from the north-central area of the island associated with the ancient civilization, when in fact it was human invasion, the appearance of malaria, and perhaps even climate change.

There follows a narrated introductory sequence showing ‘typical’ village life in which all the women are bare-breasted. While certain castes remained bare-breasted in a village setting in the 1930s, most notably the Rodi, it would be no surprise if Granemann sought out such women to titillate the audience. Certainly some of the footage is staged: a group of women winnowing then pounding rice wear identical clean white cloth that looks new and stiff. What is astonishing is that Granemann has edited in some shots of South-East Asian women, possibly from the Philippines, whose facial features, hair ornaments encircling the head, and handloom skirts with a sort of cummerbund, bear little relation to Ceylonese and their village culture. Why these shots were included is a matter for conjecture. Maybe the footage was from another of the company’s productions and used to extend the exotic nature of the sequence. Such meddling adds considerably to the phoniness of the production. As Yahoo! Movies describes the film, “topless natives, weird jungle rituals, and outrageous stock footage. From the golden era of exploitation films.”

The narration contains condescending and sensational lines such as “outwardly these simple creatures are happy and content, but in the dead of the tropical night fear clutches their hearts like a vice” and “what horrible creatures are these that suddenly blacken the skies? From what deep pit did they emerge? Their keen noses scent blood . . .”

In 1938 the 62-minute Tea Leaves in the Wind (aka Hate in Paradise) was filmed in Ceylon by the UK division of Chesterfield Motion Pictures Corporation, located in New York, which produced low-budget melodramas and mysteries during the 1920s and 1930s. The BFI provides a skeletal plot synopsis: “Plantation drama. Margot Hastings visits Ceylon with her uncle, a drink-sodden planter. She becomes involved in a love triangle, a plot to ruin her uncle and a strike by the natives, but all ends happily.” Hans Wollstein, in Strangers in Hollywood (1994), describes the film as “trite and unconvincing”.

Released in November 1938, Tea Leaves in the Wind was directed by Ward Wing, better-known as an actor. The film starred Nils Asther, a Danish-born but Swedish actor who worked in Hollywood from 1926 to the mid-1950s. He had a strikingly attractive face and played intense romantic leads opposite such stars as Joan Crawford in Our Dancing Daughters (1928) and Dreams of Love (1928), and Greta Garbo in The Single Standard (1929) and Wild Orchids (1929). In contrast he took the lead role as a Chinese warlord in Frank Capra’s memorable The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933).

Although the production company was American, the production itself was British, as the BFI states. Between 1935 and 1940 Asther was forced to work in England on low-budget films such as Tea Leaves in the Wind after an alleged breach of contract led to him being blacklisted by Hollywood studios. Asther appeared in over seventy films and for his contribution to the motion picture industry he is represented by a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

That it was a British production is further confirmed by the actors supporting Asther, who were all Britons. There was one other star, Gibson Gowland, often cast as a villain – raping Joan Crawford in Rose-Marie (1928) – who gave an astounding performance as the lead in Eric von Stroheim’s Greed (1924), considered one of the greatest films ever made. Then there was Cyril Chadwick, a versatile actor who had worked in the industry from 1913 (this was his last film), Eve Shelley, who acted in just three films, and Needham Clarke – his sole film appearance.

The Second World War and its austere aftermath curtailed further use of the island’s locations, so it wasn’t until the early 1950s that big Hollywood companies, reputed British and American directors, and a host of stars and well-known actors, arrived in force with improved equipment and experienced location personnel to make a handful of mostly acclaimed feature films.

Nevertheless the earlier period, comprising the production of just three low-budget films, is of significance in the history of foreign filmmaking in the country. All were set in Ceylon. Two were plantation dramas; a prelude to the next film set here, Elephant Walk (1954). The director of One Colombo Night, Henry Edwards, is considered one of the industry’s most enlightened and important filmmakers during the silent era.

The heart-throb star Nils Asther is named on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and his co-star William Gowland will always be remembered for his magnificent performance in Greed.

I have been handicapped in researching this article in Sri Lanka as only a preview of Jaws in the Jungle is available on YouTube. To view the rest it is necessary to sign up with Creepster.TV, and in order to take advantage of a free introductory period, credit card details must be given. However, having done so, I was informed that my credit card “was issued from an unsupported country”. In any case, at some point I received another message: “Due to third party restrictions this product is not available in your country”.

I then tried to purchase a copy at Amazon, but was told that video customers “must use a US credit card”.

What a paradox that Sri Lankans cannot see this film, whatever its flaws, which some observers say include scenes of unethically treated animals. At least the remarkable poster (far more striking than that for Bridge on the River Kwai for instance) can be easily purchased online. A specialist enthuses: “Must be seen to be believed. The stone litho colours are positively three-dimensional, and the bad kitty and crazy bat practically leap off the paper.”

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus