LK: The extraordinary role he played

Lakhshman’s connection with the Inner Temple began in 1958, when he applied to be admitted as a student, which I think in the euphemisms of this place means he’s just about there as a barrister, or student of the Inner Temple.

The High Court of Ceylon, or the Supreme Court of Ceylon, I should say, provided a certificate so that he could apply to the Inner Temple. Now you won’t be able to read it all from that distance but the important thing about it is it says in wonderfully polite language that “This man is not a mere solicitor.”

There incidentally is the original application that he made to become a student of this place and he was intensely proud of his association with the Inner Temple. However he did have one slight difference with the Inner Temple.

He was consistently critical of one aspect of the Christian tradition, which is commemorated in the Temple here, namely the tendency towards crusading. I’m not sure what his response was when he first came here to the Temple Church which, as you know, dates from 1885. It was built by the Knights Templar, the soldier monks who protected pilgrims on the way to the Holy Land. But it’s a very consistent theme in his writing. His nervousness was natural as a distinguished figure in a post-colonial society, his nervousness about western crusading.

In his journey of belief, which began within the Christian framework, from a Christian family, he moved somewhat towards Buddhism mixed with a generally syncretist approach which recognised truth in all religions. But the one thing he held against Christianity, deeply, was its tendency towards crusading. But I don’t want to blame any sins with which the Temple Church may have been associated in the past with the present generation of barristers.

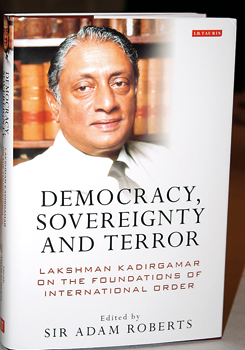

The book’s theme, and my short remarks here will reflect it, is the theme of a lawyer with a distinctively western approach in a number of ways, particularly his strong belief in democracy. A lawyer in politics and in this case in the notably violent and difficult politics of Sri Lanka.

Now, of course, he had an earlier career as a lawyer and I’ll say something about that in a moment. But the book is primarily about the speeches he made and an evaluation of his time as foreign minister of Sri Lanka. Those years from 1994 until his assassination in 2005.

I first came across him in 1964. So at that time he was back in Colombo as a practising lawyer. He had also continued to do some work in London. In 1963 he had gone to South Vietnam, as it then was, to do the first ever report for Amnesty International on a problem in a foreign country. It was because of the Buddhist revolt in South Vietnam in 1963 that he had been sent there. Both he and I had an interest in non-violent forms of struggle. It was a very interesting case of that and I think that was part of his interest in taking up the invitation from Amnesty to go there.

I don’t know and Amnesty doesn’t know the exact chain of circumstances that led to him going there. But I would place a small bet that the Inner Temple and the connections he’d made there or the connections he’d made earlier at Balliol in Oxford had something to do with it.

Having corresponded with him to try and get hold of his Amnesty report which he generously allowed me to see, I then had no contact whatever with him, until suddenly I read in the newspapers in the mid-1990s that a man with the same name was foreign minister of Sri Lanka. I then discovered, to my shock in a way, that he had actually been a student at the college where I was teaching in Oxford, at Balliol College. He’d been there from 56 to 59. So that made me redouble my determination to get in touch with him and he visited Balliol where he was as welcome as he clearly was at Inner Temple. The fellows found him a very interesting person to talk with, very courageous, very articulate, and very witty. It wasn’t too long before we belatedly caught up with the Inner Temple and made him an honorary fellow of Balliol.

On his invitation in 2005 my wife and I, went to Sri Lanka where I gave a few lectures and it was very interesting to see Lakshman in situ.

Now none of these is a good enough reason on its own to have done a book about him. I want to suggest three reasons why he was worth doing a book about. The first was, as Roslyn Higgins mentioned, he was a distinguished athlete. I’m not entirely sure whether he actually made it to Helsinki. I think he didn’t. But he certainly was the South Asian champion on the 110 metres hurdles two years in a row. Here he is, I think it was on his second victory in Bangalore in 1952. It was because of his distinction as an athlete that he was asked to be a torch bearer for a highly symbolic relay race or rather he was carrying a scroll, a scroll bearer in Sri Lanka in 1952. You can just about make him out here. He’s in the left hand row, third from the camera. He has a scroll in his hand, which he’s about to hand over to a Tamil lady.

Now it was a very symbolic relay race. It came from the four corners of Sri Lanka. These were all distinguished athletes. The last four representing each of the communities and the whole event was a celebration of the unity of the people of Sri Lanka. In a way his life symbolises the early hopes and the later disappointments of decolonisation. One could say even the early hopes and later disappointments of the decolonisation process not just in Sri Lanka, but in many countries where communal divisiveness proved to undermine some of the hopes that had been held at the time of independence. His death in Colombo over half a century later was also symbolic, but of the continuing tragic divisions in that country.

He was cremated in a square close to where that picture had been taken in 1952. A second reason for wanting to do a book about him is simply he was quite exceptionally brave. He showed that bravery in many different ways, but none I think greater then when he decided to go into politics in the first place in 1994. He was 62. He had had a successful career in the World Intellectual Property Organisation based in Geneva as an international lawyer. He’d had considerable influence on the development of intellectual property law in China and other countries. He went back to Colombo on retirement from the World Intellectual Property Organization. He set up a legal practice. He did a report, a couple of years before he went into politics, about issues that touched on the state and violence in Sri Lanka and it didn’t pull its punches. In fact it’s been widely quoted by Amnesty and other bodies. So he knew the difficulties and the dangers of politics in Sri Lanka. As if that wasn’t enough, he entered politics shortly after the death of somebody who he knew pretty well, who had also studied at Oxford and also been a minister in Sri Lanka, Lalith Athulathmudali.

But thirdly, and this was really my main interest in the book. He represented an unusual combination of beliefs. On the one hand he had an impeccable record of strong commitment to democracy and human rights.

I think part of the depth of his commitment to a), being very tough on terrorism and yet b) believing in the rule of law has to do with the fact that terrorism actually, although we like to think of it as posing a unique threat to western developed societies, actually it’s a much more serious threat to newly post-colonial states, which are still having to find their internal balance, their constitutional arrangements, even to define or redefine their frontiers and so on. They are much more susceptible to campaigns of terrorism getting out of hand or the terrorism which is started by the left and taken up by the right. Started by nationalists taken up by communists. Started by one group of separatists, then another, and that had happened in Sri Lanka. The Tamil Tigers did not invent the use of political violence in Sri Lanka, they had their precursors especially in the JVP socialist movement.

Sir Henry Brooke speaking at the book launch. Seated from left are Sir Adam Roberts, Master Rosalyn Higgins and Master Jonathan Hirst QC

Above all, his deep, deepest belief, I think, that manifested itself in his work, in his improvement of the performance of the foreign minister in Sri Lanka. While he was in office he was totally committed of establishing a serious professional and academically informed approach to the management of diplomacy and to our understanding of the world.

Actually, Lakshman’s belief in prohibition of the Tamil Tiger movement did not mean that he thought there should be no negotiation with it. He did believe that any terrorist movement has a real cause somewhere behind it. There are real political issues that do need to be addressed and that you would put yourself in a very foolish position if you said in no way we will discuss x or y, because the Tamil Tigers are pushing for it. It means that the Tamil Tigers can dictate your political agenda, if you accept that logic. He actually got into the Alice in Wonderland position. But in my view quite defensible of seeking to get the Tamil Tigers prescribed abroad. Even while at certain times he supported the de-proscription in Sri Lanka so that the government engage in ceasefire or political negotiations with the leadership of the Tamil Tigers. Actually he was cautious and astute enough to get approval in advance of the countries that had gone to the trouble of proscribing the Tamil Tigers, that he understood why he should take this special action within Sri Lanka to enable some talks to go on.

Now he achieved the feat of getting the proscriptions, because for a very material reason, large sums of money were being raised in the United Kingdom, in Canada, the United States and elsewhere from a Tamil diaspora, that was understandably concerned about events in Sri Lanka. A Tamil diaspora whose members had left Sri Lanka in many cases because of lack of jobs or a sense of discrimination. It’s not surprising, it often happens with diasporas that they then support a movement that claims to be righting the wrongs which they know about.

He succeeded in getting support of foreign governments, partly because of his knowledge of legal processes. Never better demonstrated than in his speech at Chatham House in 1998. Again the text is in the book, where he pointed to a generic problem, not just to do with the Tamil Tigers. But remember this is three years before 9/11. He said there is a generic problem that countries and especially Britain, define terrorism as a threat to themselves, but they don’t define terrorism as a threat to other countries. They’re not concerned with that and so it was perfectly possible for terrorist movements to operate within western societies with relatively little harassment. Unless and until something very very specific could be proven against them.

So he was ahead of his time and he recommended some specific changes to UK law, which in each case subsequently happened. Mainly in the Terrorism Act 2000. He never claimed that the subsequent changes happened because he had called for them. What I think was going on was something more subtle. I think through his legal friends here, including he was very close, for example, to Tom Bingham, he understood which way things were going. Being a very careful person, who did a great deal by way of checking his sources, when he quoted chapter and verse of the existing Terrorism law, he got it right. Then he recommended very specific changes. Both in the definition of terrorist acts, but also in the definition of terrorist targets as it were, what countries might be vulnerable.

So he was operating with the stream of events and I think that probably owed a good deal to his membership of Inner Temple.

Now there’s lots more that one can discuss about his extraordinary role. The rights and wrongs of the Sri Lankan struggle itself. The question of the extent to which his approach was always not successful. The question of what he would have thought of the very controversial conclusion of the Sri Lankan civil war in 2009. There’s the question of what he would have thought because he had a vision of a struggle against terrorism that was, as I said, within legal limits and respected the sovereignty of states. But he was no absolutist. He had a very practical streak in his mind and there were cases where he thought that the law would be an ass if it didn’t recognise the need for exceptions. For example, he did not join in the chorus of criticism of the NATO action over Kosovo in 1999. Even though that was without UN Security Council or without the US and Security Council’s explicit approval. There was a sort of backhanded semi approval but that’s not the same thing.

I personally think that he would probably have understood the US action against Osama Bin Laden, even though that was without the approval of the Pakistani government. But these are matters of speculation and controversy and we can perhaps come back to some of them in the discussion. But meanwhile I’m looking forward to hearing a word from Sir Henry Brooke who knew him well as a colleague of Inner Temple. Thank you very much.

Sir Henry Brooke:

This evening is taking place in the Inn which Lakshman loved in the presence of his widow. Now that Dennis Henry and Tom Bingham are both dead, I thought it might be nice if I as a bencher of the Inn, who knew Lakshman for longest, said a word or two about him before we open this up for discussion.

I first met him on the cricket field in 1958. Although we heard the rumour that he hurdled for Helsinki in the Olympics which Adam says is not true, we could hardly believe it, because he certainly wouldn’t have hurdled for anybody in 1958. But he was a wonderful colleague on the cricket field.

He had wonderful wrists for somebody who comes from that part of the world and I think he was a left-handed batsman, number five. He fully earned his place on the side. I’m not sure if I did but Lakshman certainly did.

When one met him there, everybody liked him, he liked everybody and he was one of those friends who never let go.

It’s not all that much I can say which Sir Adam hasn’t already said about Lakshman as foreign minister. He talked to us about his worries when he came to London. I remember he was exploring what was going on in Scotland and Wales with devolution on one of his visits.

He stopped being foreign minister in 2001. It was miles beyond the call of duty to go back to that job in 2004, at the age of 72. He’d been under close protection for seven years, when he was there before, under close protection again. We know what happened a year later.

I can’t remember when I last saw Lakshman. I wish I’d been able to go down again asked at short notice to an event at the Oxford Union, which celebrated him. He, I think, unveiled the photograph of himself as a very distinguished former president of the Oxford Union. I often heard him speak and I think I may have been one of the class of thousands who voted for him to be president.

I didn’t think there was anything in it. Sir Adam thinks that he loved the Inn a bit more than he loved Balliol. I think it was a dead heat. He loved England, despite the crusaders. He loved Balliol. He loved this Inn and he was a very very great friend. I was sorry when after he died that the Balliol or whatever it is, yearbook, published a obituary in the national paper, which they knew nothing about his connection with the Inn at all. I wanted to put that right tonight, by saying that we are honouring a man who did great honour himself to the Inn and was really really proud to be both a member of it and subsequently an honorary bencher.

(The book is available in Sri Lanka at Lake House Bookshop branches and Plate Ltd, 580, Galle Road, Colombo 3)

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus