Painting the pangs of Partition

Among the Zoroastrians, a small community united in their faith in the God Ahura Mazda, it is traditional to adopt one’s profession as a family name. This was why when Jimmy, the eldest son of a prominent Pakistani Parsi family, decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and study engineering, his surname was decided for him. But somewhere down the line, Jimmy Engineer changed his mind and he has instead spent the last four decades living in defiance of his name.

Jimmy Engineer

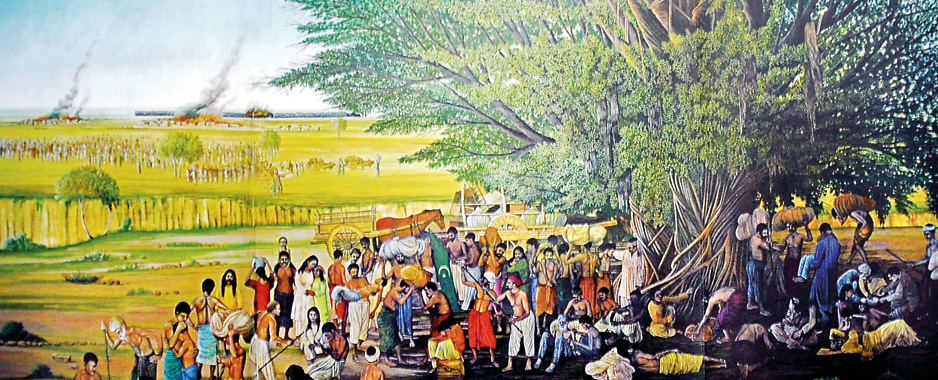

An artist of renown, Jimmy is famous for his enormous, sprawling canvases, in particular his series on the Partition of India, where literally hundreds of figures are discernable, all caught up in a violent, heart breaking migration across a nation riven with religious conflict.

The prints for Jimmy’s first exhibition here in Sri Lanka are waiting to be hung but for now are propped against the walls of the Harold Peiris Gallery at the Lionel Wendt. Looking at them, he tells me that they represent a selection of his work across 40 years. The prints, while lovely, are only a taste of the real thing. Dressed in his standard black kurta Jimmy is a tall man, but when Jimmy paints he must use a ladder and stools to work on canvases that can be seven feet high (or more) and as wide. They are pieces dense with life, each figure deserving its own moment of close study.

In ‘Refugees Resting Under a Tree in 1947,’ a 7ft by 5ft canvas painted in 1977, the eye must first take in the throng of humanity in motion, each section offering its own small tableau. First look at the old man being pulled to his feet by a father with a child on his shoulders, the woman clutching her son, eyes dilated in fright, the wounded man borne in the arms of another, the man driving his cart determinedly through the crowd, another on foot carrying the flag of Pakistan.

Now, look deeper into the painting, past this swatch of land thick with suffering people, to the shadows of thousands more walking behind, look deeper to where an overburdened train rumbles along the rails. Can you see the men dangling from its roof, determined to join the thousands already clinging to every surface? The eye cannot hope to take it all in, in a single glance or even several. Jimmy’s paintings contain entire worlds.

Jimmy says the Partition paintings came to him in dreams, their accuracy unnerving to people who had actually lived through the times. His nightmares deprived him of sleep and lingered in his waking hours and he felt compelled to put them to canvas.

“There was a fire in me to paint massive things,” says Jimmy, “I wanted to paint for people to remember that pain and agony, for them to understand that these things should not happen again.” Intertwined with this was another desire: “I wanted to honour those men, women and children who died, who never even saw the flag of our country,” he says. When the nightmares stopped, Jimmy stopped painting, but would return to the theme after an interval of 20 years. The last painting in the series, begun in 2009, remains unfinished – half drawn figures locked in conflict, dissolving into a sea of red.

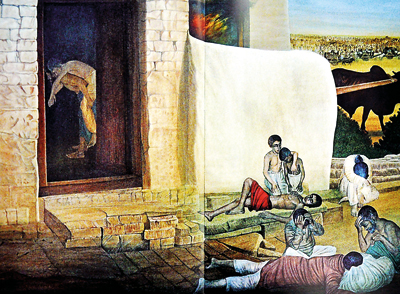

Painful past: Painting on the Partition

In between then and now, Jimmy turned his eye to several new subjects, bringing the same incredible detail to painting inanimate things, specifically his stunning Architecture series. Here he picked up iconic buildings from all over the world and put them into one canvas, creating perfectly beautiful mythical cities. The buildings are accurately reconstructed on paper, right down the rows of bricks and the placement of the windows.

Some of these focus exclusively on classic Pakistani architecture, others suggest more radical minglings, say bringing together the mausoleum of the Sultan Balban from India, the funeral complex of the Kalhora and Talpur from Pakistan and pairing them with the temple of Angkor from Cambodia. In some paintings over a dozen dislocated structures share the same space. Creating the pieces was a matter of getting the balance perfectly right, says Jimmy, explaining he took care that no single building dominated a piece, instead they existed in harmony, an allegory of multiculturalism set in stone.

Jimmy’s fierce love for his native land is immortalised in his work. Though he had more than one opportunity to immigrate, Jimmy says he never seriously considered leaving Pakistan. He has allowed his work though to find its way into museums and private collections all over the world. Ever prolific, he estimates he has over 2,000 original works to his credit, 1,000 pieces of calligraphy and over 20,000 prints in private collections in more than 50 countries. In Pakistan, where he is something of a national treasure, he has seen several of his paintings issued as postage stamps.

The diversity of his themes and mediums rival his output. Included in his oeuvre are landscapes, still-lives, paintings inspired by culture, religion and ancient civilisations, seascapes, calligraphy, miniatures, murals, abstract pieces, historical paintings, paintings on war and philosophical paintings as well as the odd self-portrait, including one of the artist as a blind man, his dark, unseeing eyes refusing to return your regard.

Despite his engagement with his art, Jimmy sees himself as a man with much more to offer. He seems to value his charitable work over his accomplishments as an artist. “I tell people I am more than one person, instead I have done so many things…My main focus is to give to a good cause,” he says explaining that he has found many in his travels.

Jimmy, who has been to Sri Lanka eight times, says he was last here in 2004 when he organised ‘Fun Camp and Food’ events for an estimated 700 children at five star hotels across the island. He is a man who has walked a great deal – raising awareness for causes as diverse as anti-child labour laws, cancer prevention and promoting peace between India and Pakistan. (1994 was a personal record – he estimates he walked 4,500 km in that year alone.) He is generous with his signed prints, donating entire sets to deserving institutions. In fact, the set at this exhibition is a gift to the Lionel Wendt, where he trusts it will be put to good use.

The exhibition of Jimmy Engineer’s works is on at the Harold Peiris Gallery until November 20.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus