Zooming back

The rock towering over the sunlight- dappled waters of the tank has no name but people at Ulpotha near Galgamuwa have begun calling it ‘Uncle Willie’s rock’. Why – because an intrepid man with adventure in his soul, though well in his eighties found a way up the mountainside to the very top and insisted that the path be cleared so that others too could ascend and enjoy the spectacular view.

William Blake’s days of rock climbing may be past but he will not miss his daily ramble round the forest at the foot of the mountain. His nephew’s rustic eco-retreat is where Willie Blake on November 16 celebrated his 90th birthday the way he wanted it- far from the city, with a few old friends, family members and his extended family- the staff at Ulpotha to whom he is simply ‘Uncle Willie’.

A great association: Lester and Willie in the old days. Pic courtesy Ajith Galappaththi

Movie-goers of a different vintage who remember the early years of Sinhala cinema will recall Willie Blake as one of the famous triumvirate – Lester James Peries, the Director, Titus Thotawatte, the Editor and Willie, the Cinematographer.

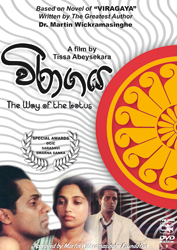

In 2001, for his contribution to cinema in Ceylon, Willie was honoured with the Golden Lion award, receiving the award from Tissa Abeysekera, then Chairman of the National Film Corporation. The citation read – “For capturing the ambience and flavour of Sri Lankan life and landscape with affection and a rare sensibility and for pioneering the shift away from the kitsch and artificiality of the studio towards a freer and more authentic and creative camera style and thereby as the main collaborator of Dr. Lester James Peries, creating a body of work which forms the dominant strand in the fabric of Sinhala film heritage, the Government Film Unit, on behalf of the Sri Lankan film community pays tribute with a once in a lifetime award of the Golden Lion to Willie Blake.”

More recently there was another award that gladdened Willie’s heart, his old school Trinity presenting him the Trinity Prize for cinematography.

Memories of those days may sometimes be a little cloudy, but Willie can remember how it all began. Straight from his schooldays at Trinity, he had joined the Navy and after the war ended served for a while in the Railway security service before joining Radio Ceylon. It was from there that he transferred to the Government Film Unit where too came Lester James Peries who had returned from England. Friends and colleagues, when Lester had the golden opportunity to make a feature film in Sinhala and was asked to go to India to find a cameraman, Willie’s chance came.

Willie recalls, “Lester went to India and came back after a week. And then I got a call from the airport. He said ‘Well I’m back.” I asked ‘How did you fare?’ He said ‘I didn’t fare very well’ and then he asked ‘Would you be ready to join’ and I said ‘sure’.”

It meant jettisoning the security of a government job but it was a decision that Willie says “I took at the right time and well, it worked” from there on, beginning his “great association with Lester”, the father of Modern Sinhala Cinema. Shot entirely on location and hailed as a path-breaker in Sinhala cinema, that film Rekava won much critical acclaim, being shown at the Cannes Film Festival.

That was 1956. Then in 1957, Willie was hired as second cameraman to British director David Lean who was shooting his epic World War 11 film ‘Bridge on the River Kwai’ in Ceylon. ‘The Bridge’ would go on to win seven Oscars and Willie recalls working with Lean as “a great privilege” and the film itself as “a landmark”.“There is not one frame in the film that is shot from anywhere else but Sri Lanka. No pick up anywhere. They got some eagles flying…I think it was the only shot that was not done here,” he says with pride.

Of Leon himself he remembers most of all the utter and total absorption in his art. “He could think of nothing but films and film-making. I had so many conversations with him, never about anything outside what we were doing. He was so absorbed in it.”

In the years that followed, Willie was Director of Photography for many of Lester’s classics, Sandeshaya (1960), Gamperaliya (1964), Delovak Athara ( 1966), The God King (1975), Baddegama (1980) and Yuganthaya (1983). He also worked on Loku Duwa with Sumitra Peries. Yet it is Rekava that is closest to his heart, “the best film I worked on. I look back on it with a great deal of affection and nostalgia. Good memories, good associates- working with Sri Lankans I had known before,” he says.

Gamperaliya too he recalls well, chuckling as he talks of the initial reaction when they said they were going to Balapitiya. “Everybody said ‘you’re going to have it. But it was our finest location. All you had to tell them was we want a chair and we would get six of them.” Author Martin Wickremasinghe too would come in occasionally and observe as the scenes from his book transferred to the silver screen.

Willie at Ulpotha: Pic by Indika Handuwala

Writing in a newspaper column Henry Jayasena who starred in the film recalled the scene: “Lester was always calm and directed his cast with utmost kindness. Willie Blake, the man in charge of the camera was a different kettle of fish. He was a hard taskmaster at work but a jolly good fellow off the sets. Often, a few of us including Lester and Sumithra would sit around the huge oval table in the hall after dinner and chat away well into the night. Willie Blake recounted some of his hilarious experiences in this ‘bioscope business’ and he kept the rest of us in stitches!”

His love for films Willie says, came from his childhood. “I was crazy about movies,” he confesses and family members recall how he would pile pillows in his bed and jump out of the window to go to the cinema at night.

Born in Colombo on November 16, 1922 to Ethel Van Heer and William Blake Snr who was a railway man, posted to Nawalapitiya, Kandy, Anuradhapura and other stations, their family of seven –Willie, Maureen, James, Jean, Estelle, Malcolm Shelley and June (James a champion athlete ran the last lap in the Independence relay representing the Burgher community) saw much of the country.

Willie remembers the travelling cinema coming to Nawalapitiya with large tents and portable projectors. While at Trinity, despite movies being frowned upon, he would miss no chance to sneak off to the Wembley cinema.

Yet, films apart there is another grand passion that figured large in his life. His enduring love for the wild and his great desire to explore and experience the country at its most elemental defined the young Willie. Intrigued by rivers, he at just 28, led an expedition down the Mahaweli. “We lived in Kandy and everything was the Mahaweli.

Nobody had done the entire route of the river, others had done sections.” Along with a small group, his wife Yvonne, brother Shelley and a few friends, they decided they should pole up the river from Mahiyangana to Trincomalee. The journey in boats made of rubber and canvas took them two hair-raising weeks through rocks and rapids, camping in tents on the river banks by night.

S.D. De Lanerolle who was part of the expedition and tells the story in the book ‘River in the Jungle’ describes Willie, the leader of the group as a man who did not know what fear was: “He had an iron will with the urge to do things which others dared not attempt”. Another river journey, this time Kalu Ganga from Ratnapura saw Willie boating down canals ending up not far from his brother Shelley’s home in Kirulapone.

Those were also the days when the young Willie would hop on a train, get off after some distance and then walk back along the tracks just because he felt that perspective was so important. He would travel with bullock carts, hopping on and off to explore- to understand what a journey at that pace felt like.

He talks with sincere respect of those he feels were the stepping stones in his passion for exploration – Dr. R.L. Spittel and Aloy Perera, an executive at Shell, an amateur film-maker whose films inspired Willie. The experiences in the wilds are never far from his mind and after dinner these days at Ulpotha, the staff gathers round to hear Uncle Willie’s tales – of the jungles of Bintenne, where nobody went in those days but where for him “it was such a thrill to be where the elephants are”, exploring the Veddah country not by jeep as one would do now, but on foot.

“I’ve had experiences in the jungle that no one else has had,” he says and of the many charged encounters, particularly with elephants, seared in his mind is the tragic death of his friend and fellow wildlife photographer Eric Swan while on a photo shoot at Tamankaduwa in September 1957. “I would say we were foolhardy,” he muses. “Nobody would stand 50 yards from an elephant hoping that things would work out. Unfortunately for us, the elephant decided to come forward. Eric had a rifle and he thought he could get the elephant but it charged. Eric was directly in its path.”

Keeping vigil over his friend’s body that night in the jungle while the others went to get help was a harrowing experience. “We just constructed a sort of makeshift shed, and made a kind of platform to put the body on. It was a terrifying night, I can tell you.”

He scoffs at the belief that when an elephant charges it puts its trunk up. “That’s all tosh. He puts it in his mouth! That’s the safe place. They (elephants) never expose the tip of their trunks which is the most sensitive part.”

In the early ’70s, Willie moved (somewhat reluctantly) to Canada with his family, wife Yvonne and three daughters, Valleri, Melanie and Sandra, going on to have a successful career doing short films with a producer in New York.

Yet his island home would keep drawing him back. There was a place in Rugam in the East that he had had since the 50s, that was to be the perfect retirement home. He loved it because there was so much history and plentiful wildlife, big herds of elephants at the Rugam tank. “I used to go on my scooter between the herd, I have passed through a herd of about 50 – maybe at that time you feel invincible,” he recalls with glee, adding that they never threatened him.

But the war put an end to that particular dream. His wife died last year and Willie is content now to spend extended time at Ulpotha surrounded by nature, close as he can be to the wild country he loves. “It’s been a good life,” he says, “If I had the choice I would like to do it all over again.”

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus