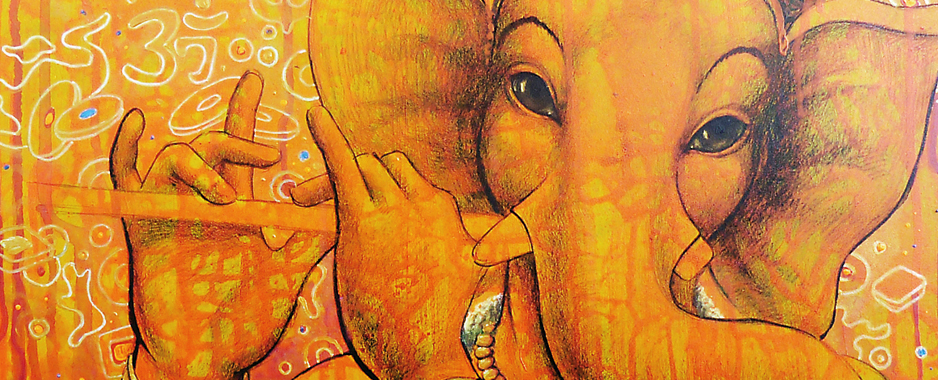

Under the gaze of Ganesh

at the Barefoot Gallery

Enter Mahen Chanmugam’s house and you will find it impossible to escape the scrutiny of Lord Ganesh. Lord of Beginnings and Remover of Obstacles, the elephant-headed son of Parvathi is everywhere: a dozen tiny Lords cast in metal observe you from their spot on the dining table and another one sits wreathed in incense by the pillar; out in the garden, hidden among the leaves, is the largest of them all but it will take you a while to notice the statues because your eyes are glued to the canvases crowding the hallway.

Here Lord Ganesh dances, dreams and plays the flute. He is light footed and light hearted, but in the depths of his warm, liquid eyes, in the rounded contours of his strange head, he seems to hold the mysteries of the universe.

When Mahen, tall and thin, sits down, his body falls into a naturally meditative pose. He knows that in a few days, the canvases will be gone, headed to the exhibition venue. “The house suddenly becomes sad,” he says ruefully, explaining that he’s only kept two paintings out of the estimated 90 he’s painted of Lord Ganesh in the last 18 years. The first of the statues, the stony behemoth in the garden, is as old as his obsession. He remembers buying it in Singapore.

He had found his way there after a stint in Hong Kong, where he worked as an illustrator/art director for Time Warner’s Asiaweek Magazine. That job had led to an offer to be an Editorial/Creative Director at HBM Publishing’s office in Singapore. Then Mahen lived life at a frenetic pace, and was out every night thanks to invitations that poured in for M3, a successful music magazine he worked on, one of several other publications. Remembering the time, Mahen says: “I was getting mixed up. It was a hell of a rat race we ran.”

Even then, Lord Ganesh seemed to have the answers Mahen was looking for. “Lord Ganesh is the one god that transcends all cultural boundaries, it’s something in his form,” says Mahen. “The further you look into it the more you understand about yourself.” Mahen has only ever looked away from his favourite subject twice: one set of three offering a searing response to political tumult which explored themes of religious violence and self-censorship and another playful series inspired by his mixed heritage. (His mother was half-Irish, his father was Tamil, his daughter is half Belgian, his son half French.) One painting from the latter hangs in his living room: a mosquito coil curled up on a bed of Celtic symbols. However, Mahen has never strayed very far, returning always to Ganesh.

Lord Ganesh speaks in these new paintings, the things he holds in his hands serving as a “philosophical template.” The noose symbolizes restraint and the bondage of desire and the axe breaks the ties of materialism.

The sweets represent the pleasures of knowledge and spiritual wisdom, while his fourth hand is raised in the symbol of enlightenment which comes from liberation of all desire. At his feet is his vehicle: the tiny mouse symbolizes the ego, which always in his service is seen as under his control. “In a time when there wasn’t a book to read, someone could look at an image and learn how to be a better person,” says Mahen.

“Painting was always a very meditative process for me,” says the artist who after years of study focused on the symbolism, iconography and the perfect postures (of which there are 32), has internalised them, allowing for a greater spontaneity in his new work. In several of the paintings, Ganesh is seen playing the flute, his music generated by his breath, his life force. “My work used to be a lot more clinical. Now I feel a much stronger personal connection with Lord Ganesh,” says Mahen, who confesses he can’t quite understand the connection, particularly since he isn’t in the least religious. “I see his image when I meditate, when I close my eyes, I see his eyes.”

One of Mahen’s personal favourites in this collection is the piece titled Thousand Petalled Lotus of Light. Practitioners of Kundalini yoga will have heard of the pinnacle state where energy surges out of the crown chakra, expanding the individual consciousness until it merges with the universal consciousness, dissolving all illusions of separateness. In Mahen’s depiction, Ganesh, he who governs the muladhara chakra, meditates with his head in the clouds, his crown dissolving into a flock of spiralling birds rising ever higher.

The bright colours of Mahen’s new pieces are echoed in the rare mirror paintings of Jaffna. Mahen encountered them years ago and says they’ve had a lasting influence on him. In this exhibition he’s attempted two pieces on mirrors and says mastering the technique has been a challenge. The pieces glimmer when they catch the light.

The paintings vary greatly in size, with the largest representing many hours of work. “I paint in this sort of stabby motion,” says Mahen, who sometimes likes to work with a dry brush dipped in acrylic paint. “It’s a repeated motion that goes on for hours, I often get lost in it.” Mahen’s approach has been hard on his hands, and he touches them gingerly when he says he’s had to deal with osteoarthritis.

Great stiffness and pain meant he had to work with a brace on, but his health has improved, allowing him to complete the paintings for Ganeshism 3 in one rush, just in time for the exhibition. Though this will be his third exhibition here, Mahen admits to being a little nervous. “Having an exhibition is almost like going there and standing naked.

Favourite possession: The statue in the garden

It must be some consolation that he still has his work as the Creative Director of MCN Creative Associates in Colombo to fall back on. His two professions have their similarities: Iconography with its clear rules and symbolic vocabulary is like a brand identity system that pervades every expression of the religion. Tongue in cheek, Mahen says “Religion is one of the oldest brands.”

Ganeshism 3, a celebration of Lord Ganesh in art is on at the Barefoot Gallery until Dec. 16.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus