Ceylon’s first flights

This month the Civil Aviation Authority of Sri Lanka (CAASL) is commemorating 100 years of aviation in Ceylon/Sri Lanka. But the first flight of an aeroplane in Ceylon took place on December 25, 1911. That’s right – 101 years ago. So why are Sri Lankan ‘aerocrats’ celebrating the centenary in 2012? Are they living up to that unkind tag bestowed on SriLankan Airlines and its predecessor Air Lanka: ‘UL’ (Usually Late)? Or is there a good reason? Let’s look at the facts, then you be the judge.

He tried and tried: Franz Oster

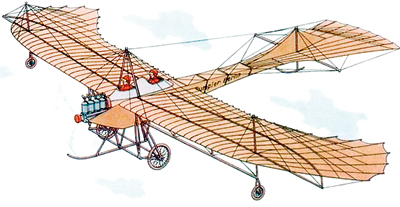

Piloting the first aeroplane to take off from Ceylonese soil on Christmas Day 1911 was an itinerant German named Franz Oster. But the story of Lankan aviation did not start with Herr Oster, because his airplane wasn’t the first to arrive on Ceylon’s shores. That distinction went to a Bl�riot monoplane similar to the one flown by French aviator Louis Bl�riot when he made the first aerial crossing of the English Channel on July 25, 1909. Ceylon’s first aeroplane arrived in Colombo on September 12, 1911, aboard the SS Rabenfels, imported by an Englishman named Colin Browne (not ‘Brown’).

Capitalising on the novelty value of this new-fangled flying machine, in November Browne put his Bl�riot on static display at the Colombo Racquet Club, charging visitors for the privilege of viewing it.

Advertisements for the exhibition hinted that the aircraft would soon be taking to its natural element for demonstration flights, and that members of the public could also pay to go on joyrides. But Browne and his Bl�riot had their thunder stolen by Franz Oster, who arrived in Ceylon aboard the Hamburg Amerika liner Silesia in late December 1911 with an airplane as part of his ‘baggage’. This was an Etrich-Rumpler Taube, a curious-looking craft, also a monoplane, whose wings and tail had a ‘feathery’ look, like those of a bird – explained by the fact that ‘Taube’ is the German word for ‘dove’.

Early on the morning of Christmas Day, in perfect weather conditions for flying and watched by five or six Europeans plus a small contingent of coolies, Oster’s Etrich Taube started its takeoff run along the Racecourse infield. According to a contemporary newspaper report, it “swept majestically past the interested spectators near the grand-stand�rising gracefully, and then descending as the aviator gradually increased its height.”

The Bleriot monoplane 1911

But suddenly things went awry for Oster and his ‘feathered’ mechanical dove with 80hp engine. Forced to bank sharply to avoid a wire strung across the course, Oster managed to miss the wire, but the violent manoeuvre caused the airplane to stall and plunge unceremoniously to earth. Although the Taube suffered considerable damage in the crash, Oster escaped injury. Thus ended, albeit ignominiously, the first flight of an aeroplane in Sri Lanka.

Undaunted, and with the Taube repaired, Franz Oster returned to the Racecourse for another attempt on December 30. But that too ended in a crash landing when a strong gust of wind flipped the airplane over and blew it onto the ground. Again, Oster wasn’t injured, but the Taube had both wings broken and its fuselage “hopelessly damaged”.

As 1912 dawned, and yet to make a successful, fully-controlled flight, Oster decided to try again. By early in the New Year, a rivalry had arisen between Colin Browne and Franz Oster, each trying to outdo the other for the honour of making Ceylon’s first successful, totally-controlled aeroplane flight. But for his third foray aloft, Oster did a deal with Browne, obtaining the use of the Englishman’s Bl�riot monoplane, which had still not flown in Lankan skies. So on January 18, 1912, Franz Oster took off from the Racecourse in the calm early morning air.

This time he appeared to be in better control, as the Bl�riot was seen climbing steadily and disappearing in the direction of the Fort. But returning to land, his airplane clipped a bamboo pole on a building at Royal College and crashed inside the grounds of the Racecourse. Franz Oster suffered a dislocated shoulder and sundry cuts and bruises, and was taken to hospital. That was the last time he flew in Ceylon.

Later that year Ceylon finally saw its first successful and completely controlled flights. This time there were two pilots and two aeroplanes: visiting Frenchmen Georges Verminck and Marc Pourpe (not ‘Pourpre’, the French word for ‘purple’, which other writers have mistakenly used), and their Bl�riot monoplanes named Rajah and La Curieuse, respectively. Commencing on December 7, 1912, and almost daily for the next week or so, the pair put on a series of ‘aviation exhibitions’ above the Racecourse, even venturing as far afield as Mount Lavinia. To the delight of awestruck spectators below, they showed off their flying skills with Gallic flair and not even a faint suggestion of the unplanned returns to terra firma that had blighted Franz Oster’s attempts.

Marc Pourpe,one of the two Frenchmen who made the first successful flight in Ceylon

As ‘flying fever’ swept Colombo like an epidemic, the Times of Ceylon newspaper scheduled an event for December 12, with Verminck and Pourpe to compete against each other for the ‘Times of Ceylon Cup’. But during one of his public demonstration flights on December 11, Marc Pourpe fell foul of the British authorities. Having taken off from the Racecourse, he overflew Cinnamon Gardens and Kollupitiya, then headed farther north. But in the aerial vicinity of Colombo Fort he strayed over the harbour and Police barracks, areas that had been ruled out-of-bounds to the French aviators when they were given permission for their flights. Upon landing back at the Racecourse, Pourpe was met by senior Police officials and taken away for questioning on suspicion of espionage. The Police also banned the next day’s ‘Cup’ event.

Ultimately, it was all deemed to be an innocent misunderstanding, but not before much huffing and puffing by the British colonial powers-that-were, with even the Governor of Ceylon, Sir Henry McCallum, becoming involved. With the Frenchman released from interrogation, the ‘Times of Ceylon Cup’ went ahead the next day as planned, and Georges Verminck was declared the victor.

Despite the unpleasantness of the ‘spying scandal’ for Verminck and Pourpe, Ceylon could finally lay claim to seeing the first successful aeroplane flights taking off from and landing on local ‘real estate’. Therefore, CAASL apparently has some justification in regarding the Verminck/Pourpe flights of December 1912 as the benchmark for centenary celebrations this year. But some aviation-minded pedants may continue to insist that the honour should have gone to the accident-prone Oster instead, and the centenary of aviation in Sri Lanka celebrated 12 months ago rather than in December 2012.

Those differing viewpoints aside, what do we know about Oster, Verminck, and Pourpe? Who were those intrepid fellows who introduced Ceylonese men, women, and children to the wonder of powered flight less than a decade after brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright did their pioneering thing at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on December 17, 1903?

Franz Oster was born on January 19, 1869 in Bad Honnef, Germany. After joining the German Navy, he sailed on a naval ship to Hong Kong.

There he left the Navy and ended up in Tsingtao (now Qingdao), China, where he ran a shipyard and established a machine factory, employing some 300 Chinese workers.

In 1909, after selling the factory and shipyard to the German government, which at the time maintained a colonial presence in Tsingtao, he returned to Germany. Learning to fly in his homeland, he bought the Etrich-Rumpler Taube monoplane. In 1911, taking his new ‘toy’ with him, he boarded the Tsingtao-bound Silesia, stopping in Colombo on the way.

After recovering from injuries sustained in his January 1912 crash in Ceylon, Oster resumed his voyage to China. When World War I broke out in August 1914, the German Governor of Tsingtao asked Oster to carry out reconnaissance flights in his repaired Etrich Taube to keep a lookout for approaching Japanese troops. But despite three attempts to get airborne, the aircraft failed to take wing and fell to the ground.

A sketch by Herge of the Etrich- Rumpler Taube with its feathery look

When the Japanese finally overran Tsingtao, Franz Oster was captured and taken to Japan as a prisoner-of-war. Even though the Great War ended in 1918, he remained in Japan until 1920, when he returned to Tsingtao and rejoined his wife and son. Franz Oster died in Tsingtao on July 19, 1933.

Marc Pourpe and Georges Verminck held pilot licence nos. 560 and 1084, respectively, issued by the Aero-Club de France.

Typical of European aeronautical adventurers of the day, they travelled to distant corners of the world and flew their aeroplanes for reward, giving people in those countries their first exposure to the new and exciting invention that was the flying machine. After their ‘aviation exhibition’ in Colombo, the French flyers and their Bl�riot monoplanes arrived in Calcutta (now Kolkata), India, on December 21, 1912. As they had done in Ceylon, Pourpe and Verminck gave demonstration flights at the Royal Calcutta Turf Club, their displays running until January 8, 1913.

From India they continued on their way, doing the same thing in other Southeast Asian countries, including Singapore. But on April 8, 1913, Georges Verminck was killed in an air crash at Saigon, Vietnam. Soon afterward, his aeronautical partner announced plans to fly to Hanoi. But not much is known of Marc Pourpe’s subsequent life story.

Although Ceylon lacked a dedicated airfield at the time, in the two decades after Pourpe and Verminck left the island there was significant aeronautical activity in the skies above the Resplendent Isle. Good harbours at Colombo, Galle, and Trincomalee were ideal ‘landing grounds’ for seaplanes operating off numerous visiting British naval ships during the 1920s. In 1928, a Fairey Flycatcher float-equipped biplane from HMS Enterprise, anchored in Colombo Harbour, very nearly caused Sri Lanka’s first fatal aviation accident. On June 8, after flying over Kandy, Lt. Edwin B. Cairnduff headed off toward the Norton Bridge area. But encountering low cloud, dense mist, and heavy rain, he crashed into a ravine while attempting to alight on a fast-flowing stream. Although the Flycatcher was destroyed, Cairnduff incurred only cuts and bruises, and walked away – literally – to a planter’s bungalow, from where he later left by car for Colombo.

One of the more noteworthy visits to Ceylon by British military seaplanes occurred on December 31, 1927 when four Supermarine Southampton twin-engine biplanes of the Royal Air Force (RAF) alighted at Colombo Harbour. They were on a record-breaking long-distance flight, for flying boats, from England to Australia, stopping at numerous ports along the way; after circumnavigating Australia the ‘flying flotilla’ reached its ultimate destination, Singapore, 14 months since leaving England.

One of the Southamptons’ commanders, Sqdn. Ldr. G.E. Livock, writing in the April 1968 issue of Air Pictorial magazine, described an incident from their sojourn in Ceylon: “Before leaving England we had not thought of one hazard – barnacles and weed on the hulls. After a few days moored in Colombo harbour we had great difficulty in getting off the water at all, owing to the drag, so we spent many hours at Trincomali (sic) taxiing each aircraft into shallow water and scrubbing the bottoms clean. On the way round from Colombo I was flying low over the shore and on rounding a headland found myself over a herd of elephants who were even more astonished than I was. One huge animal stayed on the beach thrashing his trunk at us as if swatting at a fly while his companions scattered in panic to the jungle.”

The Royal Navy and RAF aside, in the early 1930s Ceylon was a stop-over point for German civilian aviators on long-distance adventures of their own. One was Captain Hans Bertram, who touched down in Colombo Harbour in September 1931 and again in April 1932, flying Junkers F13 and W33 floatplanes, respectively, en route from Berlin to China. His first journey ended off the coast of Vishakapatnam (Vizag), India, when the F13 named Freundschaft (‘Friendship’) was destroyed in a storm. In 1932, after leaving Ceylon, Bertram and his mechanic, Adolf Klausmann, got as far as Australia in their Junkers W33 Atlantis. But there too misfortune struck, and their subsequent near-death misadventure in the remote Kimberley desert region of northwestern Western Australia became the subject of at least two books and an Australian ABC-TV series Flight into Hell.

On April 22, 1931, Lankan aviation reached an important milestone when an aeroplane flying in from another country landed on Ceylon soil for the first time. Arriving from Mandapam in South India, the de Havilland D.H.80 Puss Moth single-engine, high-wing monoplane was piloted by Nevill Vintcent. Of South African origin and an enthusiastic promoter of Indian civil aviation, Vintcent was a close friend and business associate of the legendary J.R.D. Tata, who founded the Tata Sons airline which later became Air India. Accompanying Vintcent in the Puss Moth, which landed on the Colombo Racecourse, was Zubair Caffoor, who had earlier laid claim to being the first Ceylonese to obtain a pilot’s licence.

That flight was the catalyst for many more from across Palk Strait over the next few years. On April 8, 1932 Vintcent flew India’s Director of Civil Aviation, F.W. Tymms, to Colombo, again in a Puss Moth, for talks with the government about a proposed air service between India and Ceylon.

Ceylon’s first airfield was opened at Ratmalana on November 27, 1935, when a de Havilland Puss Moth arrived from India flown by the Madras Flying Club’s chief instructor Harold Tyndale-Biscoe, accompanied by passengers W.B. Schleiter and C.B. Darius, a Ceylonese. Then on February 28, 1938, a WACO YQC-6 biplane of Tata Sons launched the first Air Mail service from Ceylon to Britain, via India. That flight also marked the start of scheduled passenger services to and from Ceylon, although by a foreign airline.

Since then, Sri Lankan aviation has progressed immeasurably if not always smoothly. Although Sri Lanka is a tiny island, its aeronautical history is rich with stories of men, women, and their flying machines. Many of those stories, recounted by this author, have been featured in the Sunday Times over the past 17 years or so, and can still be read online. Maybe some day, when the ‘centenary dust’ has settled from the sky, one or more dedicated historians with a genuine and abiding interest in the minutiae of the subject will write a comprehensive and accurate – in all respects – account of Sri Lankan aviation history.

Author’s footnote: Much of the material on which this article is based was gathered during an ongoing research project in partnership with Capt. Gihan A. Fernando, an authoritative and knowledgeable figure on the nation’s aeronautical history and lore.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus