News

Changing locations fail to mitigate man-beast conflict, says landmark study

Translocation of elephants, undertaken to mitigate the human-elephant conflict and conserve elephants, does not reduce the conflict or save elephants but causes an increase in the conflict and deaths of elephants, is the surprising finding of a study conducted in Sri Lanka.

The results of this landmark study conducted by Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando and colleagues, published in the leading international scientific journal, ‘PLOS ONE’ (accessible online at http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050917 throw light on the crucial issue of translocation, underscoring the futility of this measure and also the harm caused to elephants and people by it.

Dr. Fernando and colleagues conducted the first-ever comprehensive assessment of problem-elephant translocation by tracking 12 elephants translocated in Sri Lanka with GPS-satellite collars. They compared the ranging patterns, behaviour and involvement in the human-elephant conflict of the translocated elephants, with 12 elephants that were resident and tracked similarly with GPS.

On the road: ‘Tzu-Chi’ being translocated

The project had been undertaken as a collaborative study between the Centre for Conservation and Research (CCR – www.ccrsl.org) and the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) to find ways to better mitigate the human-elephant conflict and conserve elephants. The Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI), USA, supported the study and also provided technical expertise.

The lead author of the study, Dr. Fernando who is CCR Chairman and a Research Associate of SCBI, says that “even though hundreds of elephants have been translocated annually both in Africa and Asia, only a few have been monitored previously. Of these, only a single elephant in Kenya was tracked with a GPS collar and that too only for 13 days.

A few others have been tracked with VHF collars where the elephants have to be tracked on the ground with an antenna to find its location. VHF collars are especially unsuitable for tracking translocated elephants as they move over long distances in a short period of time and the range of the antenna is only a few km at best. Consequently VHF collars provide little data.

Because of this deficiency in monitoring most people thought that translocating problem-elephants would solve the human-elephant conflict and also safeguard the elephants concerned. Consequently, problem-elephant translocations have been continued as one of the main management actions across the range”.

Asian elephants are greatly endangered with a global population less than 10% that of African elephants. Unlike their African cousins, Asian elephants mostly live in populated areas where interaction and conflict with people is common.

Therefore, the human-elephant conflict is a major obstacle to their conservation. Most incidents of conflict with humans are due to elephant bulls, which tend to take greater risks in going after cultivated crops and stored grain. Some of these animals raid habitually, become very aggressive towards humans and are known as ‘problem-elephants’, the team stated.

One of the main methods used to mitigate the conflict arising due to such individuals is their capture by drug immobilization, transport by truck and release in a protected area. The rationale being that the elephant will continue to live in the protected area away from human contact thus solving both the conflict and conservation issues.

Dr. Peter Leimgruber of SCBI, one of the authors of the paper, says that “although translocation is a widely used tool for mitigating the human-elephant conflict, this is the first systematic and scientifically-based study on the consequences of translocation for wild Asian elephants. The results are stunning and should give cause for reconsideration of translocation as a conservation management tool. However, the collaborative project of CCR and the DWC represents a model for wildlife agencies in other Asian countries on how to assess the effectiveness, and potential detrimental effects, of elephant conservation and management measures. In the long-run such monitoring will not only improve conservation success, it will also reduce costs”.

All translocated elephants were ‘problem animals’ captured in developed areas and all were released inside National Parks under the DWC. Contrary to expectations, the study found that almost all translocated males left the park where they were released. The only exceptions were ‘Ravana’, a tusker and ‘Tzu-Chi’, which were shot dead inside the national parks before they could leave.

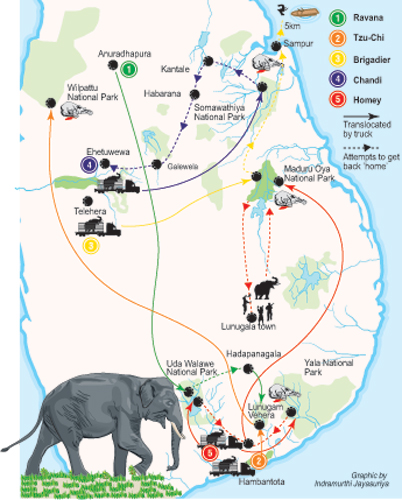

The translocated elephants showed three different patterns of ranging, says Dr. Jennifer Pastorini of CCR and the University of Zurich, a co-author of the paper. ‘Homers’ returned to the capture site, ‘wanderers’ ranged over extensive areas and ‘settlers’ settled close to the park in which they were released, she said.

The study found that all translocated elephants went back to causing human-elephant conflict. Some wandered into major towns causing chaos and widespread damage, some started raiding in new areas close to where they were released, others returned and went back to their previous patterns of raiding. Translocating problem elephants caused wider propagation of the human-elephant conflict and its intensification and decreased the survival probability of the translocated elephants.

What happened with some of the translocated elephants was quite unexpected, says Dr. Fernando. ‘Brigadier’, an elephant captured in Telehera in the north-west and released in the Maduru Oya National Park, had to go west if he wanted to go back ‘home’. However, there was something wrong with his direction finding and he went north and ended up on the Sampur shore.

‘Brigadier’ was born and grew up in the interior of the country. So for the first time in his life, he saw the sea. Amazingly, he jumped in and swam off. The Sri Lankan Navy spotted him 5 km offshore in a region that was over 300 feet deep. In a remarkable operation, two Navy divers noosed his leg under water and a boat dragged him back to shore. Then he settled down in an area close to Sampur but went back to doing what he was used to, raiding crops and breaking down houses for stored grain. After a few months, he fell into a well one night, got stuck halfway and died, he said.

‘Chandi’ with a single tusk, was captured in Ehetuwewa and translocated 93 km to the Somawathiya National Park. He left the park immediately and taking a big detour of 243 km over 29 days, came back to Ehetuwewa, journeying through Kantale, Habarana and Galewela, causing a number of incidents. He has been resident in the Ehetuwewa area since his return, Dr. Fernando says.

‘Homey’ who used to frequent an open garbage dump in Hambantota was first translocated to Yala but came back to the capture site in five days, points out Dr. Fernando, explaining that re-translocated to Uda Walawe National Park, he came back to Hambantota after 41 days. Captured for a third time and translocated to the Maduru Oya National Park, he tried to get back and walked into Lunugala town where the resulting incidents caused the deaths of two people. He was chased back to the Maduru Oya National Park by DWC officers. He then settled there but started raiding the surrounding villages. He got shot almost daily and after 15 months and much suffering died of gunshot wounds. At his death more than 300 gunshot injuries were counted on him.

Translocating problem elephants defeats both human-elephant conflict mitigation and elephant conservation goals and advocates phasing out translocation as a management tool, the study concludes. In the interim, the authors suggest limiting translocation to where it may be essential for defusing a situation of public unrest consequent to a conflict incident, while creating public awareness of its futility, which would obviate the need for such use.

They strongly recommended that any future translocations should only be done with GPS tracking and contingency plans for remedying unintended outcomes, as continuing translocations without either, amounts to reckless disregard for the lives and welfare of both elephants and people. In the long-term, human-elephant conflict mitigation needs to focus on preventing the genesis of ‘problem elephants’, the authors added.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus