Sunday Times 2

When should photographers drop their cameras?

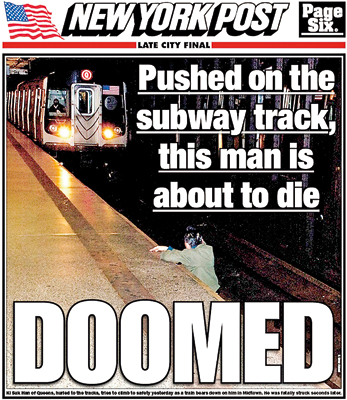

A newspaper cover showing a man seconds before his death has been widely criticised. When tragedy strikes, do photographers – professional or otherwise – have a duty to intervene?

The New York Post front page caption reads: “Ki Suk Han of Queens, hurled onto the tracks, tries to climb to safety...as the train bears down on him in Midtown. He was fatally struck seconds later”

He looks up, helpless, as the train careers towards him. “Pushed on the subway track, this man is about to die,” runs the front-page text on the New York Post. Below, in block capitals, is a single-word headline: “DOOMED.”

It’s a shocking image, and the paper’s splash has provoked an angry backlash.The photographer who took the picture has faced particular opprobrium. Why, countless social media users have asked, didn’t he help the victim instead of photographing his final moments?

Once, this ethical conundrum would have been one for journalists and media studies classes alone.

But in the age of social media, when a cameraphone invariably rests in a nearby pocket as tragedy strikes, it becomes a potential dilemma for everyone.

The photojournalist, freelancer R Umar Abbasi, insisted that he could not have reached the man – who was shoved by a stranger on to the track at 49th Street station near Times Square – and that he tried to use his camera flash to alert the train driver.

“I just started running. I had my camera up – it wasn’t even set to the right settings – and I just kept shooting and flashing, hoping the train driver would see something and be able to stop,” he said, in an article headlined My Snap Decision.

It’s not the first controversy over a powerful image of a tragic event. Photographer Kevin Carter was awarded the Pulitzer prize for his picture of a vulture stalking a starving Sudanese toddler in 1993, but he was fiercely criticised for failing to help the child. Carter killed himself a year later.

But advocates for the craft argue that even the most shocking shots are sometimes necessary to bring home the reality of the world’s horrors.

Associated Press photographer Nick Ut’s image of nine-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phuc running naked after a napalm attack was one of the defining images of the Vietnam war. Ut took the girl and other injured children to hospital and stayed in touch with her.

However, few would deny that bystanders, including photographers, have a moral duty to help those around them who are suffering.

Example from the past:Kevin Carter's Pulitzer Prize photograph of a starving toddler trying to reach a feeding center when a vulture looks on.

“You always have to err on the side of helping a human being,” says photojournalist Steve McCurry, best known for his haunting, award-winning shot of “the Afghan girl” on a 1985 cover of National Geographic magazine.

“If there’s a way to help someone, you need to put down your camera or your pen and do that.”

Nonetheless, McCurry has little time for those who attacked Abbasi for a split-second decision made in fast-moving circumstances. None of the most vocal critics, McCurry adds, witnessed the incident for themselves.

“These things happen suddenly,” he says. “There’s all this emotion and the crowds and the noise.

“You are talking about reflexes. You’re on automatic pilot.”

Stuart Franklin, who took one of the iconic images of a protester standing in front of a tank in Tiananmen Square, argues that the ethical responsibility for running the picture lies not with the photographer, but with the New York Post’s editors.

“I feel it was unnecessary – it was a sensationalist attempt to sell newspapers,” he says. “It’s the ugly end of journalism.”

The Leveson inquiry in the UK has exposed the mainstream media to greater scrutiny than ever, and tighter regulation of the traditional press seems to be inevitable. But it may be far more difficult to moderate the behaviour of the “citizen journalist”, who in this smartphone era could easily have taken the New York subway pictures.

A man blocks a line of tanks in Beijng after Chinese forces crushed a pro democracy demonstration in Tiananmen Square in 1989

“We’re going to be seeing much more of this because things like this are going to be increasingly covered, not just in photos but also on video,” says Dan Gillmor, author of We the Media: Grassroots Journalism by the People, for the People.

Pictures and footage taken by the public at disaster scenes such as those of the 7/7 attacks on London’s transport network were seen by millions.

It raises the question of whether ordinary members of the public have an obligation to start thinking about media ethics in the same way as the most experienced war correspondent.

But advocates of citizen newsgathering – who value the capacity of amateurs to get to places professional reporters often can’t – say it would be a mistake to hold everyone to the same standards as veterans of the craft.

For Jay Rosen, professor of journalism at New York University, the onus is on publishers to ensure that what they put out is ethically sound.

“Since the tools for making media have been distributed to the people formerly known as the audience, the scene where professional ethics ‘happen’ must shift to the filters that news organisations apply when they decide what to publish,” he says.

No doubt the debate around the Post’s cover will continue. If nothing else, it illustrates yet again the timeless power of a photograph.

(Courtesy BBC)

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus