Doctor turns patient

It was a busy morning in the operating theatre. I was the consultant anaesthesiologist responsible for the patients on the operating list, but in a moment my role was reversed. A fall resulted in a fracture of my femur, and suddenly I was a patient. A five-month stay in hospital ensued, which taught me several lessons.

Lesson 1 – The doctor is a God in the patient’s eyes

My friend and colleague, the orthopaedic surgeon was summoned and he rushed over to attend to me. His gentle touch and kind words comforted me and I felt an overwhelming gratitude towards him as I would towards a benevolent God. The God-like impression was probably heightened by the operating theatre light forming a halo around his head!

Lesson 2 – Laughter is the best medicine

Jokes abounded in the anaesthetic fraternity concerning the incident. I had fallen while teaching medical students about a spinal anaesthetic for which my registrar was scrubbed up. As he related later, “I could have caught her as she fell, but I didn’t; as she has always stressed the importance of sterility in spinal anaesthesia, and would have scolded me for contaminating my gloves!”

Another joke doing the rounds amongst the doctors in the Intensive Care Unit was “Just imagine what it would have been like if she had been admitted to our ICU! We would have been under her eagle eye all day and night.

She would have issued orders – “Hey! Check out the patient in bed number 4!”

These and many more kept me entertained and made me forget my pain.

Lesson 3 – Physiotherapy is a form of torture, but a necessary evil

Anticipating that my muscles already weakened by childhood polio, would hamper recovery, physiotherapy was started early. Not having had time for regular physiotherapy in the past due to busy work schedules, I wasn’t sure which of my muscles were functioning and which weren’t.

Muscles long out of work were re-employed, muscles which I never even knew existed. After all, my knowledge of Anatomy was acquired as a first year medical student in 1973, and quickly forgotten by 1974, once I got through the first exam!

Physiotherapy was painful work, even more painful than the fracture itself, and I began to hate physiotherapists. “Hey mister! I’d just like to see YOU do these exercises with a fracture and a heavy plaster to boot!” I thought. But in my heart of hearts I thanked them for devoting valuable time and effort on me.

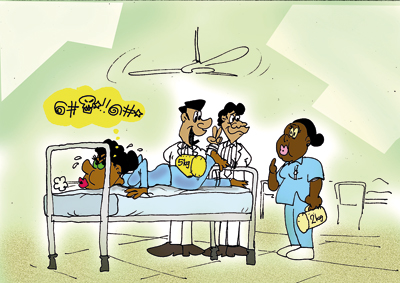

Once, two of my trainee anaesthetists came to visit me when I was in the Physiotherapy department. I was lying on my face lifting up a five kilogram weight with my fractured leg, and let me tell you, that isn’t an easy task.

My abdomen was compressed by the hard surface of the bed, which pushed all my abdominal contents up against my diaphragm, which, as we were taught in Physiology, reduces lung volume. So there I was, gasping for breath and just about managing to lift the five kilograms when my trainees said “Oh you can do that easily!” and called out to the physiotherapist, “Can you put on 2 more kilos here?” If my lung function had allowed me, I would have roared at them, but as things were, I could only manage a feeble protest.

Lesson 4 – Establishing rapport with patients is very much easier when you yourself are a patient

As students we had been taught that the first step to a good clinical history was establishing rapport with the patient. I had prided myself on my ability to do this, but found that I could communicate much more effectively, now that I was a patient. Clinical histories came tumbling out from other patients without my even asking them, and although I was an anaesthesiologist, my advice was sought for all types of problems – in cardiology, paediatrics and even dermatology. A sort of camaraderie existed between the long term patients there. We were all fellow sufferers joined together in our pain and disability. Although they knew that I was a doctor, I was one of them. We encouraged and comforted each other.

Lesson 5 – Being a strict disciplinarian does not make one unpopular

I had been strict with the trainee anaesthetists, my key words being Punctuality, Reliability and Responsibility. Most of them, at some time or the other, had felt the sharp edge of my tongue. But they undoubtedly had very forgiving natures, because as soon as word spread of my fall they came to see me, and the numbers were considerable – there are 43 anaesthetists in our department. I was touched by their love and concern.

They were with me throughout my stay in hospital, and my room became an ‘on call’ room for them. I enjoyed the unending stream of visitors and the bits of hospital gossip that they conveyed. Every single meal during those five months was brought by them and I sampled not only Sinhalese and Tamil cuisine, but Indian, Chinese and Italian as well! It was better than restaurant food – this was homemade and delicious. Word spread that there was enough and more food in my room, and once, after midnight, when the doctors in the casualty theatre were hungry, one had the bright idea of waking me up and asking for food – any food! Although I did grumble at having been put up at that time, I was glad to oblige.

One of my colleagues commented “If I fall ill I doubt whether my two children will give me even half the care that you’ve had. You’re very lucky!”

I answered “I know I’m lucky. You’ve got only 2 children, but I’ve got 43 children looking after me!”

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus