Sunday Times 2

‘The godfather of world music’

Ravi Shankar, the Indian sitar player whose sound had a major influence on The Beatles, has died at the age of 92. Besides working closely with George Harrison, he also collaborated with musicians as diverse as violinist Yehudi Menuhin and jazz saxophonist John Coltrane.

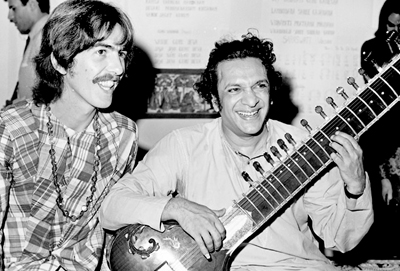

Eye Opening: George Harrison, of the Beatles, sits cross-legged with his musical mentor, Ravi Shankar of India, in Los Angeles in 1967

A statement on his website said he died on Tuesday in San Diego, near his southern California home, with his wife and one of his two daughters by his side. The musician’s foundation issued a statement saying that he had suffered chest and heart problems and had undergone heart-valve replacement surgery last week.

Indian prime minister Manmohan Singh called Shankar a ‘national treasure’.

Labelled ‘the godfather of world music’ by Harrison, Shankar helped millions of classical, jazz and rock lovers discover the centuries-old traditions of Indian music through the sitar, the long-necked stringed instrument that resembles a giant lute.

However, the sound was so unusual to Western ears at the time that some fans mistook his tuning up for actual music. Shankar’s close relationship with Harrison, the Beatles’ lead guitarist, shot the Indian musician to global stardom in the 1960s.

Harrison had grown fascinated with the sitar and played the instrument, with a Western tuning, on the song Norwegian Wood. But he soon sought out Shankar, already a musical icon in India, to ask to be taught to play it properly.

The pair spent weeks together, starting the lessons at Harrison’s house in England and then moving to a houseboat in Kashmir and later to California. Gaining confidence with the complex instrument, Harrison recorded the Indian-inspired song Love You To on the Beatles’ Revolver album, helping spark the ‘raga-rock’ phase of 1960s music and drawing increasing attention to Shankar and his work.

Shankar played the 1967 Monterey Pop festival and at Woodstock in 1969 and also pioneered the concept of the rock benefit gig with the 1971 Concert For Bangladesh, where he appeared alongside Harrison and other stars.

Moved by the plight of millions of refugees fleeing into India to escape the war in Bangladesh, Shankar reached out to Harrison to see what they could do to help.

In what Shankar later described as ‘one of the most moving and intense musical experiences of the century,’ the pair organised two benefit concerts at Madison Square Garden that included Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan and Ringo Starr.

The concert, which spawned an album and a film, raised millions of dollars for UNICEF and inspired other rock benefits, including the 1985 Live Aid concert to raise funds for famine relief in Ethiopia and the 2010 Hope For Haiti Now telethon.

To later generations, he was known as the father of popular American singer Norah Jones, although the pair were estranged.

Shankar also composed a number of film scores – notably for Satyajit Ray’s celebrated Apu trilogy (1951-55) and Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi in 1982 – and collaborated with avant-garde US composer Philip Glass in Passages in 1990.

His last musical performance was with his other daughter, sitarist Anoushka Shankar Wright, on November 4 in Long Beach, California. His foundation said it was to celebrate his tenth decade of creating music.

The multiple Grammy award winner had learned the night before his surgery that he was to receive the lifetime achievement honour at next year’s ceremony.

Neil Portnow, president of the Recording Academy of America, said: ‘He was deeply touched and so pleased.’

He added: ‘We have lost an innovative and exceptional talent and a true ambassador of inter- national music.’

As early as the 1950s, Shankar began collaborating with and teaching some of the greats of Western music, including violinist Yehudi Menuhin and jazz saxophonist John Coltrane.

He played well-received shows in concert halls in Europe and the United States, but faced a constant struggle to bridge the musical gap between the West and the East.

Though the audience for his music hugely expanded after his mainstream success, Shankar, a serious, disciplined traditionalist who had played Carnegie Hall, chafed against the drug use and rebelliousness of the hippie culture.

‘I was shocked to see people dressing so flamboyantly. They were all stoned. To me, it was a new world,’ Shankar told Rolling Stone of the Monterey festival. While he enjoyed Otis Redding and the Mamas and the Papas at the festival, he was horrified when Jimi Hendrix lit his guitar on fire. ’That was too much for me. In our culture, we have such respect for musical instruments, they are like part of God,’ he said.

Ravindra Shankar Chowdhury was born April 7, 1920, in the Indian city of Varanasi. At the age of 10, he moved to Paris to join the world famous dance troupe of his brother Uday. Over the next eight years, Shankar travelled with the troupe across Europe, America and Asia, and later credited his early immersion in foreign cultures with making him such an effective ambassador for Indian music.

During one tour, renowned musician Baba Allaudin Khan joined the troupe, took Shankar under his wing and eventually became his teacher through 7 1/2 years of isolated, rigorous study of the sitar.

‘Khan told me you have to leave everything else and do one thing properly,’ Shankar told The Associated Press.

In the 1950s, Shankar began gaining fame throughout India. He held the influential position of music director for All India Radio in New Delhi and wrote the scores for several popular films.

He began writing compositions for orchestras, blending clarinets and other foreign instruments into traditional Indian music.

And he became a de facto tutor for Westerners fascinated by India’s musical traditions.

He gave lessons to Coltrane, who named his son Ravi in Shankar’s honour, and became close friends with Menuhin, recording the acclaimed ‘West Meets East’ album with him. He also collaborated with flutist Jean Pierre Rampal, composer Philip Glass and conductors Andre Previn and Zubin Mehta.

‘Any player on any instrument with any ears would be deeply moved by Ravi Shankar. If you love music, it would be impossible not to be,’ singer David Crosby, whose band The Byrds was inspired by Shankar’s music, said in the book ‘The Dawn of Indian Music in the West: Bhairavi.’

Shankar’s personal life, however, was more complex. His 1941 marriage to Baba Allaudin Khan’s daughter, Annapurna Devi, ended in divorce. Though he had a decades-long relationship with dancer Kamala Shastri that ended in 1981, he had relationships with several other women in the 1970s.

In 1979, he fathered Norah Jones with New York concert promoter Sue Jones, and in 1981, Sukanya Rajan, who played the tanpura at his concerts, gave birth to his daughter Anoushka.

He grew estranged from Sue Jones in the 80s and didn’t see Norah for a decade, though they later re-established contact.

He married Rajan in 1989 and trained young Anoushka as his heir on the sitar. In recent years, father and daughter toured the world together.

When Jones shot to stardom and won five Grammy awards in 2003, Anoushka Shankar was nominated for a Grammy of her own.

Shankar, himself, has won three Grammy awards and was nominated for an Oscar for his musical score for the movie ‘Gandhi.’

Despite his fame, numerous albums and decades of world tours, Shankar’s music remained a riddle to many Western ears.

Shankar was amused after he and colleague Ustad Ali Akbar Khan were greeted with admiring applause when they opened the Concert for Bangladesh by twanging their sitar and sarod for a minute and a half.

‘If you like our tuning so much, I hope you will enjoy the playing more,’ he told the confused crowd, and then launched into his set.

© Daily Mail, London

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus