The case for conserving elephant landscapes

View(s):Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne on the need for large scale thinking for elephant conservation

Nilantha Kodituwakku and I instinctively exchanged looks. Had we imagined it or was that elephant by the Habarana Trincomalee Road wearing a radio collar? It was 4 a.m. and we had not really been looking out for elephants as we made an early morning dash to look for Blue Whales in Trincomalee with the team at Chaaya Blu. I was intrigued about the radio-collared elephant and I knew someone who would know more about it. That person was Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando (Pruthu) who has pioneered radio tracking studies of elephants in Sri Lanka and is the author of several papers on elephants.

Coincidentally the day earlier I had phoned Pruthu on my way to the Cinnamon Lodge where the John Keells Hotels Nature Trails team were taking us on safari for the Elephant Gathering, the largest annually recurring concentration of elephants anywhere in the world, listed by Lonely Planet as among the top ten wildlife spectacles in the world.

I had spoken to Pruthu as I wanted to learn more about what his studies had revealed about the usage of the different parks and reserves by elephants in that area.

Fighting a jumbo battle: Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando

A few hours later, I was in Kaudulla National Park on an evening game drive. It was magical. We estimated that over 200 elephants came out onto the lake bed. At least three groups of elephants numbering over forty each visited the water.

The leaders of the in-coming and outgoing groups seemed to greet each other. Later, as the evening wore on, most of the safari vehicles had left and we watched two young bulls tussling with each other in a mock fight.

This will prepare them for the real thing to come later as they mature and leave the family group to fend on their own. Nature Trails naturalist Nilantha Kodituwakku rolled the video camera capturing footage which I would use later at Whale Fest in Brighton in October 2012 to show how closely the social behaviour of elephants and sperm whales mirror each other.

I have been coming to The Gathering for many years and in the last ten years my focus had been on raising awareness of it and publicising that it could be worth a billion rupees in annual revenue. Its economic value will be crucial to creating the political will not just to preserve the existing national parks and reserves but also the forested areas which link them.

Elephants roam over large areas and to conserve them it is not sufficient to protect just the designated parks and reserves. An entire landscape, an elephant conservation landscape needs to be conserved. The designated parks and reserves and remaining forest are crucial elements. But the elephant conservation landscape will be much bigger and encompass roads, hotels, petrol sheds, farms and all the other products of human civilisation.

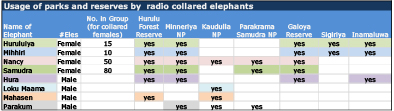

To understand this better, I met with Pruthu and his wife Dr. Jennifer Pastorini to understand how elephants utilise the landscape. I had listened years earlier to Pruthu at a lecture where he had explained that a bull elephant could range over 140 square kilometres. He has also for several years together with other scientists and conservationists been lobbying for viewing the conservation of elephants in terms of large-scale conservation landscapes. I was interested in how much the elephants in the Kaudulla- Minneriya-Hurulu complex ranged over their area. Did all of them range over all three designated protected areas, were there any that only used one protected area or was it a mix?

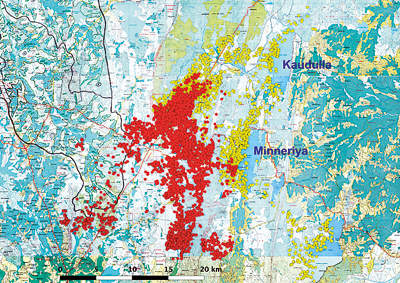

Radio collar data: Red (Mihiri) and yellow (Nancy)

Answers to such questions can be found using photographic identification of elephants. But this is arduous work and it may take many years of effort before meaningful results can be obtained. Radio collaring is a brilliant shortcut which provides accurate results of an animal’s movements.

Around 67 elephants have been radio collared by the Department of Wildlife Conservation in collaboration with Pruthu’s organization the Centre for Conservation and Research, over the past 15 years. The radio collared elephants relay their coordinates captured by an on board GPS at four hour intervals which are sent as a packet of information. These elephants have provided a wealth of data that can be used for better management and conservation.

The table above illustrates how the 5 radio collared elephants use one or more of the designated protected areas in the Kaudulla-Minneriya-Hurulu complex. From this table alone it is clear that elephant conservation cannot work with just one protected area. An entire complex has to be protected with interlinking areas.

The satellite tracking maps tell another important story. The amount of area used by the elephants outside the protected areas. It also paints a compelling portrait of how entire conservation landscapes have to be conserved to protect these wide ranging animals.

According to Pruthu, a radical mind shift is needed to conserve wide-ranging mammals like elephants. Stand alone pockets of forest will not suffice. It holds true with almost every species that a network of interlinked forested areas work better for conservation as it maintains gene flow and provides a natural backstop if the animals at one site are extirpated by a natural or man-made disaster.

With elephants there is an additional complication as they do better outside the parks in disturbed areas than in undisturbed forest in the parks. However, when they are outside protected areas conflicts arise with people, especially when they raid cultivation. There are no easy solutions and one way forward is to adopt the concept of elephant conservation landscapes and to integrate elephants even more firmly into the national economic agenda through tourism.

Elephants can also be made to pay their way by being a positive media tool to brand Sri Lanka internationally in a favourable light.

This will be through hours of documentary coverage as well as what this unusual elephant island is doing to conserve them. However to reap the publicity dividend, the country will need to make it as easy as possible for film crews (especially foreign film crews) to film them. This would mean abolishing the need for film permits.

This requires breaking away from the current mindset of one or more state agencies striving to make a few thousand dollars in filming permits and thereby sacrificing millions of dollars of favourable brand publicity which will generate money elsewhere in the economy.

The future of Sri Lanka’s elephants may lie in whether the country’s decision makers are savvy and experienced enough to make the country open for business like their political and civil service counterparts do in developed nations.

Wildlife writer Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne can be found on Facebook, Flickr and LinkedIn.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus