News

One leap more before our Kalu Wandura disappears forever

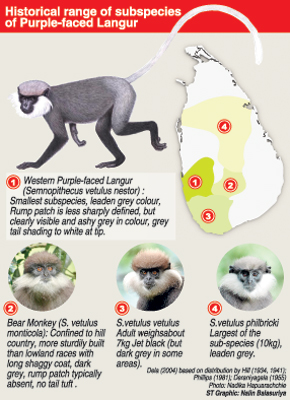

View(s):Our Kalu Wandura, or Purple-faced Leaf Monkey, is among the world’s 25 most threatened primates, writes Malaka Rodrigo

The “Kalu Wandura”, or Purple-faced Leaf Monkey, is close to extinction. This monkey, which once flourished in the Wet Zone and was a regular visitor to gardens in Colombo, is a disappearing species. The 2012 National Red List on Conservation Status of Species warns that it is “critically endangered.”

Dr. Jinie Dela, a primatologist who has been studying the Purple-faced Langur for the past 28 years, says this monkey is among the world’s most threatened 25 primates.

The late Banana, beloved of primatologist Dr. Jinie Dela. The picture was taken by a villager.

“Habitat degradation and habitat loss is the main threat to this primate,” Dr. Dela says. The past few decades have seen changes in land use in the Western Province, particularly in the Colombo and Kalutara districts, where the Western Purple-faced Langur once abounded. With urbanisation and high land prices, home gardens are shrinking and the number of food trees available for monkeys and humans is dwindling, the expert says.

“Many rubber plantations have been cleared for housing, industry, roads and other infrastructure. Large trees are being cut down, and the monkey-human conflict is escalating as man and monkey compete for the few fruit trees that are left in pocket-sized home gardens. Monkeys damage tiled roofs when they cross them to close gaps in arboreal paths, resulting in more conflict.”

Up to the mid-’80s, Dr Dela recalls, the kalu wandura was not an unwelcome visitor, but in recent years the human community has become less tolerant.

The loss of tall fruit trees means these monkeys must come down to unusually low elevations, even ground level, in search of food. This makes them highly vulnerable to dogs, poachers, and others intent on killing them. Monkeys in urban areas also get electrocuted by power lines and run over by vehicles when they cross roads. Monkey-friendly habitats are fragmenting and disappearing even in the countryside, and extinction is a strong likelihood.

Dr. Dela recalls the tragic end of her favourite monkey, Banana. Banana was a young adult in his prime and the leader of a monkey troop that Dr. Dela was studying. Barely two years after he asserted his role as leader of his troop, Banana was shot dead while feeding on mangos in a home garden. Without a male leader to protect them, Banana’s adult female companions were taken over by a “Thug Troop.” The group eventually scattered. Banana’s infant son, Dodi, died of tetanus from a bite by an invading adult male monkey.

“I can barely recognise the neighbourhood where Banana once lived. I used to follow his little family from dawn to dusk,” Dr. Dela told the Sunday Times. “The generation that comes after Banana will face even greater hardship and worse threats. The range of typical Western Sub-species is even smaller than we thought and none of the forests in it are viable refuges in isolation in the long-term.”

In a three-year conservation project on the Western Purple-Faced Langur, researchers Dr. Dela, Dr. U. K. G. K. Padmalal of the Open University, and Anura Sathurusinghe, Conservator, Research and Education, Forest Department, travelled more than 7,000 km to obtain data from 450 sites in the Colombo, Kurunegala, Gampaha, Ratnapura, Kalutara and Kegalle Districts. They trekked through at least 50 forests to assess monkey populations and forest conditions. “Most forests are small and isolated amid villages and plantations,” the expert says. “The langur was common in less than a third of the sites we surveyed, and was absent or rare in most.”

These monkeys can live up to 20 years or more, but their life span is decreasing as threats mount.

“The population crash, when it comes, will be sudden and it will be too late to take action,” Dr. Dela says, emphasising the need for conservation action before it is too late.

Citing a separate case of imperilled monkeys, the Northern Sportive Lemur of Madagascar, of which only 19 individuals are known to be living in the wild, Dr. Dela says: “Let’s hope our own Western Purple-Faced Langur will be luckier.”

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus