Lanka’s own Dani Girl tugs at heartstrings with ‘Danny Boy’

View(s):For a second time, Danielle de Niese delighted Sri Lankan audiences – moving many to

tears – with her arias, art songs and encores.

Stephen Prins attended her concert in Galle

D riving, or rather superhighway racing, to Galle was our first thought after attending the Sri Lanka-Asia debut concert of opera star Danielle de Niese on November 14, at the Cinnamon Grand. Galle was where she would give her second concert, one week later. We had to enjoy a repeat of the riches we had just heard in a performance that was “great”, “grand”, “glorious” – to quote music-lovers present that November 14 evening.

Danielle de Niese sings in Sri Lanka

The internationally acclaimed lyric soprano, with family roots in Sri Lanka, had overwhelmed us with the beauty of her voice, her cinematic good looks, her vibrant stage presence, and the fullness and warmth of a very generous personality. This was one special lady, and she had given us one special concert. That performance was the most sheerly enjoyable and dazzling classical music experience we have had in a long, long time.

The Galle concert was a reprise of the Colombo programme, with the minor difference that in Galle diva de Niese had two pianos and a classical guitar to accompany her, whereas in Colombo she had in addition a chamber music orchestra on stage. If de Niese were to be accompanied by a solo harmonica, she would still ravish her audience.

By the time de Niese arrived at the Jetwing Lighthouse, she had already seen and enjoyed a sizeable slice of local life and culture in her first experience of the country of her parents’ birth; the de Niese entourage travelled from Colombo to Dambulla and Nuwara Eliya before proceeding to the port town of Galle. You could sense the opera singer now felt thoroughly at home in her ancestral homeland, and seemed even closer to her audience, which responded with like warmth to de Niese’s bubbling presence.

With a true artist, the pleasure in the art deepens with repeat exposure. On the afternoons of November 12 and 13, we sat in a dark corner of the Cinnamon Grand, eavesdropping on diva de Niese rehearsing with her musicians, going through the same song, same phrase, same note, over and over. Both the Colombo and Galle concerts ended on an exultant note, with singer and audience falling madly in love with each other, and exchanging encores and standing ovations.

Danielle de Niese, who is “Dani” to family and friends, told the audience that she and her mother, whom she described as the greatest influence in her life, had worked hard on compiling a programme they hoped would touch a chord with a Sri Lankan audience. This applied equally to the main works and the encores.

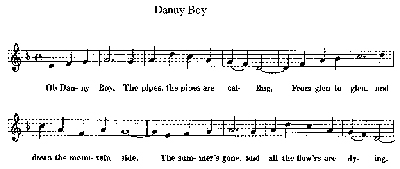

One encore was the song “Danny Boy,” a favourite with an older generation of Sri Lankans, or Ceylonese. De Niese warned the audience that the song was a tearjerker and that she hoped her voice would not crack with emotion. Her rendering of “Danny Boy” could not have been more poignant. The song must have touched a deeply responsive chord with many present in the audience.

In our case, we were reminded of “Londonderry Air,” the traditional Irish melody on which the words of the song “Danny Boy” are strung. We would hear plaintive “Londonderry Air” played on the violin by all the violin students who came home for music lessons. It was one of the first pieces a beginner was taught.

When it was our turn to play “Londonderry Air”, we performed it on the keyboard. It was one of the early pieces in the beginner’s album, “Everybody’s Favourite Classical Piano Pieces.” Like Schumann’s “Traumerei” and Delibes’ “Waltz from Coppelia”, this was one of the pieces in the book that carried a genuine sweet-sadness that even an eight-year-old could appreciate.

Whenever the song “Danny Boy” came over the radio, Father would recall going to the old Empire Theatre as a schoolboy to see a British film of the ’30s with the same title. “Danny Boy” was the film’s theme song. Father was 16 years old and with him was his aunt, Agnes Spittel, Principal of St. Paul’s Milagiriya Girls’ School. When aunt and nephew came out of the theatre and climbed into a rickshaw to head home, Agnes Spittel remarked to Father, “With all the sadness there is in this world, must they make films as sad as this?” The movie was wrenching, and Father had a strange faraway look whenever he recalled that depressing film-going afternoon in 1935.

Recently, we opened the glass-faced cabinet where Mother kept the family violin and piano music. We pulled out our ancient copy of “Everybody’s Favourite Classical Piano Pieces.” We took the book to the piano and turned to “Londonderry Air.” The plain, plaintive melody cried out on the out-of-tune piano and plaintive family memories came back.

Looking at the music score, at the simple uncluttered contour of the melody, an unadorned line of rising and falling notes free of sharps and flats, as pure as a melody can be, we recalled an observation made many years ago by a family friend and musician. That observation, a technical-emotional music insight, was, in fact, the subject of a fiery letter to the newspapers fired by the dreaded music critic, Elmer de Haan.

Sometime in 1969-1970, Elmer de Haan heard a radio programme by a visiting music scholar who was giving a series of talks on Schubert songs. The scholar mentioned in passing the general rule familiar to all music students that a melody in a major key was “happy”, while a melody in a minor key was “sad.”

Ever the controversialist, Elmer de Haan thundered back with a letter to the Ceylon Daily News, saying the visiting musician’s thesis of “major for joy and minor for sorrow” was downright wrong and misleading. He cited examples from the classical music repertoire of the major key being used to produce an effect of “sadness” and the minor key being used to evoke “joyousness.”

The letter was typical of Mr. de Haan, who delighted in seizing any opportunity to display his formidable music erudition and skewer anyone with pretensions or a lesser knowledge of music.

The evening of the day the article appeared, Mr. Elmer de Haan turned up at our home as usual. At the time he was paying us daily visits. He enjoyed Father’s company, and the opening topic that evening was his coruscating letter to the editor on major and minor keys. Father, who was not a musician and not in the least interested in the nuances of Western Classical music, patiently listened. De Haan asserted that the major key was by nature “more refined” than the minor, and therefore in its purity of sound a better vehicle for conveying emotions of melancholy and sadness than the minor key, with its coarse flattened third, sixth and seventh notes.

For weeks, Mr. de Haan’s letter was the talk of the music circle, as well as the diplomatic and expatriate community, to which the victim of the letter belonged. Some wags described de Haan’s letter as a “major noise on a minor music matter,” but nobody could dispute the examples de Haan had given to prove his point.

That major-minor point was one of dozens of insights into the mysteries and marvels of music that the brilliant and eccentric Mr. de Haan inflicted on the public, and our family, over the years.

The “major for sadness” thesis fitted perfectly the melody of “Londonderry Air”, or “Danny Boy.” The tune, set in F major in the “Everybody’s Favourite” version, remains firmly in F major all the way, without even one note lapsing into a relative minor key. And it is one of the most poignant melodies ever.

Danielle de Niese and her mother were right. “Danny Boy” did have a special meaning for members of the Sri Lanka audience. It certainly did in our case. As she sang, with piercing expressiveness, the Irish song’s beautiful sad strains brought back memories and faces of people long gone, important individuals who had key roles in our childhood, growing-up years, and music education.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus