News

Wet veggies rot as deluges hike prices

View(s):Unseasonal intense downpours inundate cultivated land destroying produce and its production in the foreseeable future. Namini Wijedasa reports from Dambulla, Kurunegala and Anuradhapura

Mounds of pumpkin lay on the floor of the Dedicated Economic Centre (DEC) in Dambulla. Gunny sacks full of imported onions and potatoes were piled up high.

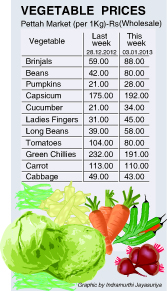

But with downpours continuing in most of the country’s crop-growing areas last week, other vegetables were in shorter supply than usual. This drop has now pushed up wholesale and retail prices. Traders predict that price levels will remain steep till at least April, when a fresh influx of produce is expected to drive them down.

Vegetables affected by the heavy rains displayed for sale at the Dambulla Economic Centre. Pix by Indika Handuwala

One of the main problems crippling vegetable production was that the intensity of rainfall experienced in December had caused plants to shed flowers. The ground was waterlogged in badly affected areas, while wet conditions hindered transport.

“Look at these onion leaves,” said a trader at the DEC, pulling apart a large bunch of ripening, yellow sprigs. “We got these batches only yesterday evening. Already they are yellow.”

This trader, who asked not to be named, showed how the sheaves of onion leaves were wet at their cores, when they usually arrived in a dry state. He also displayed how beans had developed spots induced by an excess of rain. Radishes and beets were being sold with their leaves sliced off, because the foliage rotted faster. And many brinjals—of which there was a noticeable shortfall—were also patchy and spongy.

“Usually, we get about 500 bags of brinjals a day,” said Samantha Sisira Gunaratne, a sales assistant, on Thursday. “Today, we didn’t even get 50.” Each bag contains 50kg. He also said there was no ‘ela batu’ in the market, while other vegetables like sponge gourd (‘vetakolu’) and tomatoes were fewer in number.

Gamini Ekanayake

Mr. Gunaratne explained that cabbages were particularly “allergic” to wet conditions. “They will be covered in slime within a day of delivery,” he said. With a higher percentage of low quality vegetables entering the market, prices were erratic.

“When there is a stock of good vegetables, buyers try to grab it at higher prices,” explained Umesh Gayan, who works in his uncle’s wholesale shop. “When low quality stocks come in, the prices go down. At present, the quantity of substandard vegetables is higher, because most of what we receive is ‘vehi elavalu’.”

The best produce, habitually, went to Colombo, with buyers from the capital paying around Rs 10 more for the goods. Onions and potatoes from India and Pakistan were available in plenty at the Centre. So, too, were pumpkins, as they were a more durable crop that could be stored for up to two weeks—or more—after harvest. But traders now had trouble disposing of pumpkins.

“We have a pile of pumpkins to sell, but no buyers,” said Umesh Gayan, “We were offering them for between Rs 10 and 15 a kilo. As they didn’t move, we will dispose of them at any price.”

The Centre, which is usually swarming with buyers in the afternoon, was still comparatively uncongested. “On dry days, it is so crowded at this time, that you can’t move about,” said H.R. Nissanka. “It’s empty now, because it is difficult for minor vegetable sellers to transport their goods, village markets are bare of people due to rains, and the small-time vendors don’t want to risk buying too much, in case they can’t sell them off.”

“When it pours so hard, consumers prefer to stock up on potatoes and dhal, so that they don’t have to go out,” he said.

The supply of vegetables from the hill country, such as Nuwara Eliya, was also slow, because of rains and landslides. Traders predicted that growers everywhere will start cultivating vegetables soon, with the New Year in mind.

Large tracts of paddy have also gone under. In some areas, however, paddy plants have recovered after the water drained off. The most damage was observed on sides of canals and other pathways through which water had gushed with some force.

“Rice plants can survive under water to up to five days,” explained Agriculture Department’s Natural Resources Management Centre Director Dr. W.M.A.D.B Wickramasinghe.

“Look at these onion leaves”

Dr. Wickramasinghe cautioned, however, that the damage is yet to be assessed. The high estimates taken just after the floods could change as rainwater drains off. The impact of flooding in areas such as Ampara, Batticaloa, Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa and Vavuniya, among others, was likely to be worse, because of their flat to undulating terrain.

“When you get more water, there is no slope to release it,” he said. “So you will find stagnant pools everywhere.”

Paddy lands in the Kurunegala district were reported to have been badly affected. The Sunday Times visited the village of Peddava in Mahamukalanyaya, Kurunegala. Rice fields were flooded due to the Deduru Oya overflowing.

The area’s Farmer’s Association President Gamini Ekanayake said houses close to the river were submerged in up to nine feet of water. He said around 100 acres of paddy went under water.

“The worst is when silt stays on the paddy and they start to rot,” he explained. “We have seen some of that.” The government has promised to distribute new seed paddy, but Mr. Ekanayake said this was not practical.

Kivulekada tank surged six feet overnight

“The paddy plants in adjoining fields are around two months old,” he pointed out. “If we sow the fields again, pests and diseases from all around will get attracted to the new plants, because they prefer tender shoots and leaves. Our farmers have tried this in the past and failed.”

There is no vegetable cultivation in Peddava. Elders said, only 10 to 15 perches of arable land in the village was suitable for vegetables. The rest were all paddy lands, with the majority being tended to by tenant farmers.

Gunaratne Banda is one such tenant farmer. He had sown paddy on a large tract of land near the Deduru Oya, but parts of it were washed out when the river burst its banks.

“I was badly affected by the drought some months ago,” Mr. Banda, a father of two said. “I couldn’t work the fields at all. Now these fields have been hit by rains. I will earn some money by working my sister’s fields and doing manual labour.”

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus