Then there were jungles

View(s):Beginning our series of the memoirs of well-known naturalist, Rex de Silva

| These are the memoirs of a naturalist. The title “From Ocean Depths to the Stars” is a reflection of the things that fascinate me viz. the jungles, ocean and the heavens. My first encounter with the natural world was with the jungles of Sri Lanka. In Part 1 of these memoirs, I attempt to present to the reader a feeling for the jungles that once existed in Sri Lanka; through a recounting of my various encounters and experiences. Alas these jungles are now almost gone, save for a few artificially protected habitats viz. national parks, sanctuaries etc. which, as far as I am concerned, are a far cry from the relatively unspoiled forests of six decades ago that I knew so well. The changes are dramatic, especially when viewed from the perspective of time. |

The Jungle

“There are some who can live without wild things, and some who cannot. These essays are the delights and dilemmas of one who

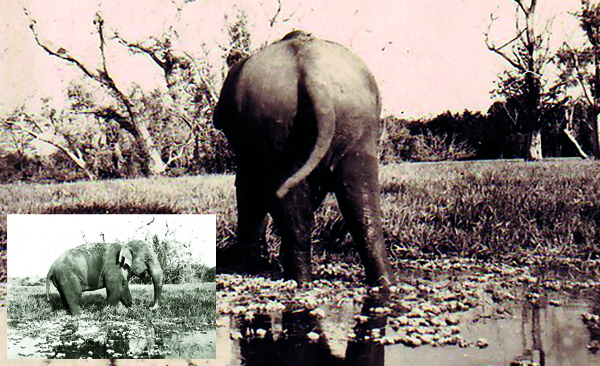

Amparai mid 1950s: It is easy to see how Walige Kota got its name (plate 2, above) and Walige Kota in Amparai Tank (plate 1, inset)

cannot”. (Aldo Leopold)

In the 1950s my family lived in the Gal Oya Valley. All my school holidays and spare time were spent in Amparai, where my activities consisted almost exclusively in shooting, fishing and exploring the jungles. Nearly six decades ago only a fortunate few could afford the luxury of four-wheel drive vehicles. The rest of us walked. This was probably a blessing in disguise, as to really know the jungle one must walk. In time I became an excellent trekker who could easily cover 10 to 12 miles of jungle trail in a day. I also became a reasonably competent tracker. Reading signs is one of the best ways to learn about the animals occurring in an area and their activities.

Equipment

In the 1950s selection of equipment was a matter for great consideration as everything had to be carried on one’s person. Primary on our lists was suitable footwear, and many were the discussions on the relative merits of the different kinds available. Next in importance were hats, with some preferring the “Terai” and others the Australian “Bush hats” while I, like most others, wore a common or garden variety cloth hat. Knives came next, not for fighting wild beasts, but for more prosaic uses around the camp. I used a Parker Hale knife with a five

Mid 1950s: Kaira of Mullagama, one of the finest Veddah hunters (plate 9)

and half inch blade which I kept razor-sharp. Some preferred the American K-bar knives but mainly it was a question of “use whatever you have”. Also important were matches for starting camp and cooking fires. Much discussion centred upon keeping them dry. I had no problem in dealing with damp matches; merely running them a few times through my hair dried them out. Of course a preferred method was to dip the match heads in nail lacquer which made them waterproof. The problem was that the striking surface of the matchbox could not be easily waterproofed. The long American red-headed matches were especially valued as these could be ignited by striking against any rough surface; denims for instance, thereby obviating the need for a matchbox. Of course the legendary Zippo lighters were highly prized, but few owned them. Other things that concerned us were remedies for tick bites and stomach problems, antiseptics, wound dressings and of course mosquito repellents. Luxury items included magnetic compasses and binoculars, but most of us did without them.

Hunting

There is a primal allure to hunting, and I was not immune to it. My heroes were the great professional hunters of yore; men like John Taylor, Selous, “Karamojo” Bell, Jim Corbett and others. I fancied myself following in their footsteps. My hunting proclivities were supported by my companions of the day. Forest Ranger Bevis Ekanayake, hunter and tracker par excellence was several years my senior and I look upon him as my mentor. Bevis was highly regarded for having tracked down and shot a proclaimed man-killer, the “Kantalai Rouge” elephant which killed over half-dozen villagers in the Kantalai-Welikanda-Punnani areas in the early 1950s. Another companion was “Jackson” Perera who had been badly mauled by a leopard and proudly bore the scars left by its claws and teeth on his head, chest and shoulders. (Jackson is said to have killed the leopard with a knife but, being a fairly reticent person, he would only smile when asked for details). My other occasional field-companion was Kaira of Bingoda (plate 9) , one of the finest of the Veddah hunters.

In the 1950s jungles could be dangerous to those on foot, so most of us carried firearms when possible. This was especially so when walking and camping at night. As a ranger, Bevis, had a small arsenal at his disposal including a Winchester 70 chambered for the powerful Holland and Holland .375 magnum cartridge and his personal 12 bore Webley and Scott double barrel shotgun. Jackson used his father’s Harrington and Richardson single barrel 12 bore shotgun. Most of the Veddahs and jungle villagers used decrepit muzzle loaders, usually with coils of copper wire binding the barrel muzzles to (hopefully) prevent them from bursting when the trigger was squeezed. My armament was an old single barrel 12 bore Lerage shotgun with fore-end fastened with a piece of rag to prevent it falling off when the weapon was fired.

Nevertheless with the exception of the single encounter related below, I never had to use a firearm to protect myself.

Next encounter : Kabaraya a good eight feet below the writer (plate 4) |

Amparai mid -1950s: Kabaraya a few minutes before charging the writer (plate 3) |

Encounter with a bear

In the mid-1950s Bevis and I were in the jungle about 2 miles south of Kondawattawan tank. We were walking through an abandoned chena in which termites had built a mound in the hollowed out trunk of a fire-burnt tree. We did not realise that a bear was feeding on the termites. Without warning it charged us growling loudly. I barely had time to thumb the hammer and fire a quick shot; almost simultaneously Bevis emptied both barrels of his Webley and Scott at the creature. The bear, badly wounded, fled into the jungle. It was a basic principle that an injured animal had to be followed up and put out of its misery as quickly as possible.

This was to prevent any further suffering to the injured animal, as well as to ensure that it did not pose a threat to other passers-by. We searched for the wounded bear until dusk with no success and decided to return at dawn the next day to finish the job. On approaching the place of our encounter the following morning we met a villager who informed us that the bear lay dead more than quarter mile away. The corpse was a pitiful sight; and I had a deep sense of remorse and pity for this once proud animal. But there was no alternative; had we not opened fire one or both of us could have been badly mauled or worse. Many jungle villagers bore the terrible scars and injuries from encounters with bears. A few were rendered blind and some killed. We were fortunate in being able to protect ourselves.

Elephants

Elephants were very common in the valley. Towards dusk, a small herd would frequently cross our front garden on their way to feed in the nearby sugarcane plantation. They would return, in ones and twos at dawn. Late one night I heard a sound outside my bedroom window and on looking out saw an elephant, which had broken the boundary fence, feeding on my mother’s prized cannas, which it ate with great gusto.

Most of the elephants were not offensive and provided one kept a safe distance, posed little or no threat to humans.

A particularly well-loved elephant was “Walige Kota” (plates 1 & 2), a frequent visitor to the Amparai tank margins. Walige Kota never harmed anyone. This did not save it from a cultivator’s bullet in the early 1960s.

Quite in contrast was “Kabaraya”, a feisty, aggressive and quite dangerous elephant that had demolished several bicycles, a bullock cart and also smashed up the “Triumph” motorcycle belonging to the Amparai Parish Priest. It was rumoured that Kabaraya had killed a man, but I was unable to verify this. Many, but not all its attacks took place at night. The elephant would charge in, whereon the terrified humans would abandon their vehicles and seek refuge in the jungle. Kabaraya would then proceed to demolish the vehicles. The frightened bullock escaped but the cart was reportedly reduced to matchwood. Kabaraya was a frequent visitor to the wilder margins of Amparai tank, and we often encountered each other in my almost daily peregrinations in the jungle. Kabaraya hated everybody and everything so I always gave it a wide berth.

One afternoon we met in the shallows of Amparai tank where Kabaraya was feeding on submerged grasses. Although I was behind a shrub and careful to keep downwind, a stray gust of wind must have warned of my presence and the animal strode away towards the jungle with obvious annoyance. Foolishly, casting caution to the winds, I followed in order to obtain a photograph (plate 3) with my father’s Rolleicord camera which I was carrying. Even the soft click of the shutter was too much for its hair-trigger temper and wheeling around Kabaraya charged me. I ran faster than I had ever done, and I can still imagine its footfalls behind me. As I fled in absolute panic, I chanced upon a survey line which intersected my line-of-flight; I plunged into this and ran on until exhaustion overcame me. After some time I regained my breath and my heart stopped its pounding. There was no sign of Kabaraya. I was young, fit and reasonably athletic: this, together with a great deal of good luck undoubtedly helped me survive. (The survey line was a straight path cut into the jungle for the purpose of giving surveyors, in this case the survey students of the Technical Training Institute (now Hardy Institute), a clear sight-line for them to practise with their theodolites and other survey instruments. They were not intended as foot-paths).

It was sometime before I regained my zest for elephant photography and the next time we met I made certain that I was safely on the elevated bank of a stream while Kabaraya was on the almost dry stream bed a good eight feet below me (Plate 4). Being charged by a dangerous elephant while one is on foot is probably among the most terrifying experiences anyone could have. Friends sometimes wonder at my lack of interest when they talk about the elephant that “charged” them in Yala; for I know full well that they were in the safety of a vehicle.

Each year in November, during the heavy rains, herds of elephants would join together in the forest around the Uhana airstrip forming a “super herd” (today this would be called a “gathering”). One rainy afternoon, while waiting at the airstrip to meet my father who was arriving in the old Air Ceylon, Dakota (DC3) aircraft from Colombo, my attention was drawn to the elephants. Having nothing to do until the aircraft arrived I began to count them, and had reached 141 when the plane landed and I had to leave. Mr. Wilmot Ekanayake (Bevis’s father), who was also present, told me that he had counted over 160 animals.

This reminds me of the inaugural Air Ceylon flight from Colombo to Amparai. The plane carrying a full load of dignitaries was unable to land because a few elephants had invaded the airstrip. After some effort the elephants were chased away and the plane was finally able to touch down. Buffalos also caused delays in the Air Ceylon flights as on occasion a whole herd would venture on to the airstrip while the Dakota had to fly in circles until the animals were dispersed.

(Part 2 next week)

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus