Their forefathers were foes

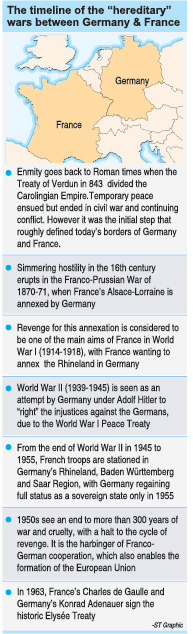

View(s):The 50th anniversary of the Elysee Treaty, that brought to an end the centuries-old bloody hostilities between France and Germany falls on Tuesday. Here the two ambassadors share the reconciliation process that united two bitter enemies. Kumudini Hettiarachchi and Shaveen Jeewandara report

The bitterest of foes, now the closest of friends!

How did these two neighbours who have waged war on each other from time immemorial, having shed precious blood, sweat and tears, stretch the hands of strong friendship across their borders not only to say “never again” but also to stand together and become two powerful members of Europe?

French Ambassador Christine Robichon and German Ambassador Dr. Jürgen Morhard on the reconciliation process. Pic by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Millions had laid down their lives, many are still unaccounted for, livelihoods had been destroyed and families left in shambles on both sides of the border, down the years, but France and Germany have risen from the ashes of numerous wars, the most recent being World War I (WWI) and World War II (WWII).

The simple instrument that has yielded such powerful benefits of reconciliation has been the Elysee Treaty, the 50th anniversary of which is drawing nigh and will be celebrated on Tuesday (January 22, 2013) a historic lesson coming down from 1963 not only to countries at peace but also for nations warring within and without.

In a palatial house down Alfred House Avenue, Colombo 3, overlooking a beautifully manicured garden, we meet two “descendants” whose parents, grand-parents, great-grandparents and relatives had been on opposing sides of the divide, before the Elysee Treaty.

Now very much a part of officials as well as the public, holding the treaty as their guide, are none other than German Ambassador Dr. Jürgen Morhard and French Ambassador Christine Robichon, both serving in Sri Lanka.

Many similarities emerge as their families’ sagas unfold, though on opposing sides, also reflecting the stories of millions of their countrymen and women.

Great-grandfathers, grandfathers, fathers and uncles had fought the battles of their countries, be it Germany or France, while the great-grandmothers, grandmothers, mothers and aunts had attempted to keep the families from crumbling and the home fires burning while their menfolk were away.

With his hometown, Pirmasens being only 25 km from Alsace-Lorraine, the French border was only a stone’s throw-away for Ambassador Morhard, having both advantages and disadvantages. Flipping back the pages of time, he points out that between 1798 and 1814, his hometown came under the French Department of Mont-Tonerre after Napoleon’s revolutionary wars. Closer in time, after WWI, in 1923-24, a separatist movement in his hometown attempted to establish a pro-French administration, but failed.

The hostilities between the two countries were always simmering and it was during WWI that his maternal great-grandfather was taken a prisoner-of-war (POW) and his grandfather “kept writing letters to the administration” not letting the flame of hope die.

“The best they could do was write letters,” says Dr. Morhard wryly, adding that although he was released after the war, his paternal branch of the family was not so lucky. His paternal great-grandfather and grand uncle went to war, with his great-grandfather encouraging his son with the words, “My brave son, you exchanged your school books for a soldier’s uniform in order to go where German heroes fight and the German flag is held high. Although I may worry about you, my heart rejoices as I would have made the same choice. Go my son, be brave! And should you die, my Fatherland take him”. Both were killed on the western front in France, leaving his grandmother’s family not only sorrowful but also in the doldrums, with its livelihood destroyed.

Between WWI and WWII, however, the family was able to stabilize again by selling construction material for the huge wall that was being put up on the defence line (Siegfried or Westwall) with France, he says matter-of-factly.

For Ambassador Robichon’s grandparents, WWI was equally traumatic. While both grandfathers were drafted to the French army, her grandmother was left to run the family farm on her own. “She was a gifted girl, had come first in the district at an exam like the OLs but had to stop her education and run the farm,” she says. When the grandfathers came home after the war they were mere shadows of their former selves as they had been seriously wounded.

Still closer in time, WWII was devastating. In 1939, on evacuation from their hometown, Ambassador Morhard’s grandfather remained to command a bunker at the border, while the family got scattered.

The frontlines were shifting and the family did return to Pirmasens in 1941, but in an air-raid in 1944, became homeless once again, with the business razed to the ground. It was also the same year that his father, just 17, his uncle, 18, and his grandfather went to war. His father had been taken prisoner in Normandy, the day he turned 18 – September 18, 1944, experiencing the horrors of war.

A photo taken on September 22, 1984 shows German Chancellor Helmut Kohl (L) and French President Francois Mitterrand walking together in the military cemetery of Douaumont, near Verdun, during a reconciliation ceremony on the site of the Verdun battlefield. (AFP)

Without any skill, he was oiling the gears of cranes, says Dr. Morhard about his father’s days as a POW. Even when the war ended, the family was in disarray, their home destroyed and no business left. “They had lost everything and when my father was freed, the family told him not to come back because they just couldn’t feed him,” he says. So it was that his father, even though a free man, remained in France for two years now as a “guest worker” on construction sites, also “perfecting his French”.

The family, however, is not without its war-scars, 68 long years after the war. There can be no closure, for his teenage uncle who joined the troops, never came home and is “missing in action”, believed to have been a POW in Russia. His aunt is still looking for her brother’s grave, says Ambassador Morhard with emotion, adding that as a child he never heard his father talking about the war and the suffering. He never complained about the past, for he didn’t want us harbour any bad feelings about France, only wanted to promote friendship. It was gradually when asked about the scars on his stomach, that little bits of information came forth, about a botched up appendix operation under questionable conditions, while a prisoner.

In the case of Ambassador Robichon’s father and his family, they were living in Burgundy but had close ties with a German family in Ludwigsburg, which have continued to the third and fourth generations. “My father like my grandfather studied German in secondary school,” she says, adding that in August 1939, her father who was 16 was in Germany when an official from the consulate advised that he leave for home immediately. He boarded a train, “they say it was the last train to cross the border” before WWII broke out, she adds.

Trains seem to have played a role in her family, for as the German tanks rumbled and the army marched towards Paris, they were among the millions of people who fled their homes, carrying only what they could. “My family had got on a train that was supposed to transport cattle,” she says, adding that there was “huge displacement” of people.

Her family did come back in two weeks, to find that their home had come under heavy bombing as it was close to a strategic railroad. By that time France had been divided and her parents were in the northern part under the Germans, where unimaginable deprivation and severe rationing were the order of their lives.

To avoid being commandeered to work in Germany (as German youth were fighting the war) under harsh conditions that many would not survive, her father after graduating from school had left the family and crossed the demarcation line to the unoccupied part of France. Under cover of night, he had been smuggled across the river in a small boat, along with a Jewish family fleeing the persecution of the Nazis, to the Alps. This was while an uncle of hers who was an officer in the French army was a POW in Germany under trying circumstances, the health consequences of which he suffered long after his release.

But, after WWII, contact with the German family resumed, she says, pointing out that German was the first foreign language that she learnt and she spent a lot of time with that family. “Recently, there was a function to welcome my nephew’s fiancée and the German family was invited,” she says.

When WWII ended and the two countries attempted to limp back to normalcy, dawned the realization not only among the two governments but also the people that there were no winners and losers, no victors and vanquished. War takes a toll on each and every one and all human beings need to live with dignity.

This was the nurturing ground for the Elysee Treaty, the essence of which is reconciliation, with a lesson learnt by two “hereditary” enemy countries and may be a lesson to be learnt by many other countries.

The Elysee Treaty

History stood still on that cold wintry day, half a century ago when “arch enemies” sat together at the Elysee Palace and signed a document that would change the collision course that had been the norm for France and Germany.

It was January 22, 1963 and the signatories were French President Charles de Gaulle and German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer.

“The Elysee Treaty has been a landmark in the history of both our nations. It is a political and legal framework for a lasting reconciliation between our governments,” says Ambassador Robichon.

The element of reconciliation in the treaty and the measures that have followed could be a model for Sri Lanka which has been torn apart by 30 years of conflict, she adds, a view echoed by Ambassador Morhard.

A precursor to the treaty had been the important speech in fluent German that President de Gaulle delivered in Ludwigsburg in 1962 to German youth, giving them dignity and cementing German-French cooperation.

There was no attempt to apportion blame or guilt, says Ambassador Morhard, it was an exercise to make sure that the same mistakes would never-ever be made again, with equal respect being paid to soldiers and civilians on both sides.

Different governments, different ideologies, different colours may have come and gone in both countries but the promise made that day, 50 years ago, holds good, intensifying with time and within the framework of the European Union, says Ambassador Robichon, with Ambassador Morhard agreeing.

And it was in 1984, in Verdun, one of the largest battlefields, where German and French soldiers had fought for 300 days and 300 nights under horrific conditions during WWI that French President Francois Mitterand and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl also had a historic meeting of reconciliation.

At this place where 900,000 soldiers laid down their lives or went missing in action, the two Heads of State did not shake hands, but held hands, strengthening the bonds of friendship and sending a strong message for reconciliation, without questioning or doubting each other’s responsibilities.

The Elysee Treaty has been followed by: Joint government meetings every six months; more than 2,200 partnerships (twinning) between cities and regions; exchange programmes between German and French Youth Associations under which 200,000 have gone across to the other country; more than 4,300 school partnerships; a Franco-German university network covering 160 universities with 4,700 students in 150 joint-degree programmes; France being Germany’s most important trading partner; the common TV Channel Arte; and close professional relationship between the French and German diplomatic services.

A major step in the right direction under the treaty has been the “harmonization of history” of the two countries.

“One of the many initiatives taken under the umbrella of the treaty, a Youth Parliament proposed the development of joint textbooks for history,” said Ambassador Robichon, explaining that historians and history teachers of both countries met and the textbooks were published in both French and German in 2006, 2008 and 2011.

It synchronizes both the histories in a neutral, objective way, to prevent distortions and the subsequent use of such material as a propaganda tool, adds Ambassador Morhard.

Franco-German celebrations here

While a joint session of Parliament of both countries will mark the 50th anniversary celebrations of the Elysee Treaty, far away in Sri Lanka a poetic and musical evening, ‘Le voyage interieur’– a spiritual journey, Herman Hesse, will be held, with the poems being recited in both German and French, on January 24 at 6.30 p.m. at the Goethe Institut.

This will be followed on January 31 by a Conference on ‘The Elysee Treaty: Meeting of two prominent political personalities — Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and President Charles de Gaulle’ at the Goethe Institut by the President of the Association of Friendship Germany-Sri Lanka, Helga Olga Schafheutle.

A week’s culinary experience, ‘Taste of Europe’ at the Cinnamon Lakeside where Chef Alfred Melchoir from the border province of Alsace will present his skills will also be part of the celebrations.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus