From Ceylon to Amazonia

View(s):The Theosophical Quest of Colonel Percy Fawcett

By Richard Boyle

When the South American explorer, archaeologist and Theosophist Colonel Percy Henry Fawcett went missing in the Amazon in 1925, the world believed it happened on a much-publicised expedition in search of what he called the “Lost City of Z”, possibly inhabited by descendents of an ancient civilization. However, in 2004 it was revealed in a theatre production concerning Fawcett staged in London that he was in fact attempting to implement what he termed “The Great Scheme”.

This was to found a colony in Amazonia for people to escape materialism and develop mystic consciousness; and to deliver his eldest son Jack – who, before his birth in Ceylon, was foretold by Buddhist monks to be the reincarnation of an advanced being – to the “Earth Guardians” as an initiate.

Colonel Percival Harrison Fawcett: British explorer in the late 1800s, early 1900s who mapped great portions of South America

After a mental transformation, Jack would be installed as the founder and leader of a mystic colony in his birthplace. Thus the real story of Fawcett’s disappearance starts with the prophecy of Buddhist monks in Ceylon, Trincomalee to be precise.

Ceylon’s connection with what was essentially a theosophical adventure is just part of an extraordinary story that involves the unknown fate of Fawcett and his son, the number of often reckless rescue expeditions mounted, the shocking number of lives lost, and the contemporary media interest: major television productions, books, and a possible Hollywood movie.

Information regarding The Great Scheme and the manner in which Fawcett’s youngest son, Brian, cunningly deceived the world regarding his father’s intentions, was discovered when theatre writer/director Misha Williams gained access in the early years of this century to a previously closely-guarded family cache of what he termed the “Secret Papers”. Research resulted in Williams’ play, AmaZonia, which he described as “a dark comedy”, first performed on April 15, 2004, at the Bridewell Theatre. Surprisingly, the revelations regarding Ceylon seem not to have filtered through since then.

***************************

One of my favourite books as a young teenager was the bestseller Operation Fawcett, aka Lost Trails, Lost Cities in the US (1953), credited as having been written by Colonel Fawcett and edited by Brian Fawcett. This exhilarating Amazon adventure introduced Fawcett to the world long after his disappearance a quarter of a century earlier. The book was said to be based on Fawcett’s notebooks of his expeditions prior to his disappearance, starting with the first in 1906 after a frontier dispute arose between Brazil, Bolivia and Peru. The Royal Geographical Society of London, of which he was a member, was asked to mediate and sent Fawcett to make a survey of the area in question. Significantly, he had perfected the surveyor’s craft in Ceylon.

Operation Fawcett became the Book of the Month, was reviewed by Graham Greene among other luminaries, described as “full of mystery, fortitude and doom”, compared to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and translated into many languages. No one was aware then that it was not an authentic autobiography: Fawcett’s actual autobiography, “Travel and Mystery in South America”, was never published as the manuscript was lost while being shunted between potential publishers in 1924. Brian Fawcett used the adventurous parts of his missing father’s notes to make Operation Fawcett a compelling read, but much of the rest was fictitious, written by him to guarantee the world remained unaware of the true quest.

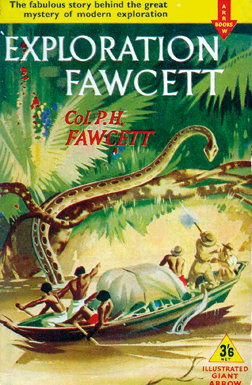

My principal fascination for Exploration Fawcett was the description of an encounter with a giant anaconda, a dramatic illustration of which adorned the cover of my 1960s paperback edition.

“We were drifting along below the confluence of the Rio Negro when almost under the bow of the boat there appeared a triangular head and several feet of undulating body. It was a giant anaconda. I sprang for my rifle as the creature began to make its way up the bank, and smashed a .44 soft-nosed bullet into its spine below the wicked head. At once there was a flurry of foam, and several heavy thumps against the boat’s keel.

“With great difficulty I persuaded the Indian crew to turn in shore-wards. They were so frightened that the whites showed all round their popping eyes, and in the moment of firing I had heard their terrified voices begging me not to shoot lest the monster destroy the boat and kill everyone on board.

“We stepped ashore and approached the reptile with caution. It was out of action, but shivers ran up and down the body. As far as it was possible to measure, a length of 45 feet [14m] lay out of the water, and 17 feet [5m] in it, making a total length of 62 feet [19m]. Its body was not thick for such a colossal length – not more than 12 inches [30cm] in diameter – but it had probably been long without food. Everything about this snake was repulsive.”

The book set me on the road to becoming a writer as it inspired a short story concerning an anaconda, a revered resident of a Mayan temple, which won second prize in the Brooke Bond National Travel Scholarships and Educational Awards in England in 1964.

Curiously, at the turn of the century, my interest in the anaconda was rekindled on reading the obscure “The Anaconda of Ceylon”, an absurd report of a giant anaconda found on Colombo’s outskirts. Published in Scotland in 1768, this fantasy provided the first instance of the name anaconda in English, later bestowed on several large South American snakes but probably derived (with unintended Dutch assistance) from the Sinhala henakandaya. (See “The Anaconda of the Ceylonese”, “The Vanquisher of Tygers” and “The Amazonian River Monster”, The Sunday Times, June 25, July 2 & 9, 2000; or Chapter 4, “The Anaconda of Ceylon”, in Sindbad in Serendib [2008].)

******************************

The Fawcett story, as I shall relate it, is based on both published information and Misha Williams’ research among the Secret Papers presented in a lengthy preface to his play Amazonia http://www.fawcettsamazonia.co.uk/together with my Sri Lanka-oriented observations.

Fawcett was born on August 31, 1867, in Torquay, England. His Indian-born father, an equerry to the Prince of Wales and a fellow of the Royal Geographic Society, was an alcoholic who died aged 45. His mother, of Scottish ancestry, was a Celtic mystic. He had an elder brother, Edward Douglas Fawcett, also a Theosophist, and of equal interest in many ways. For instance he was a pioneering science-fiction author. Hartmann the Anarchist or the Doom of a Great City (1893) foretold the Blitz of the Second World War and pre-dated HE Wells’ The Shape of Things to Come by 40 years, while The Secret of the Desert, or How We Crossed Arabia in the “Antelope” is the first fictional account of an armoured vehicle, 20 years before the invention of the tank.

Fawcett never engaged with his family, rejected his parents’ lifestyle and became an academic loner. He was, apparently, “snubbed and maltreated by his parents” and was forced into the Army because his mother “adored the lovely uniform”. His abhorrence of the military could have had an adverse effect on his life, but when he received a commission in the Royal Artillery in 1886, aged 19, and was sent to Fort Frederick, Trincomalee, it “set his whole future on a unique and devastating course”. Shunning the drinking, gambling and interracial sex indulged in by his fellow officers, Fawcett became keenly interested in archaeology and travelled inland to the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa region “to seek out strange and ancient ruins and record hieroglyphs”.

Cover of Exploration Fawcett as described by the writer

Once he was caught in a storm and forced to spend the night in the jungle. At dawn, mist shrouded the area. When it lifted, Fawcett saw before him a rock covered with large hieroglyphs. He made a copy and upon his return to Trincomalee consulted an erudite Buddhist monk, who believed they disclosed the existence of a vast treasure buried beneath the rock during a time of disaster. Later, Fawcett made the same inquiry at the Oriental Institute, Oxford, where he was informed that he would have to revisit the site in order to take a rubbing, since the meaning of the characters changed according to the angle of the sun’s rays. Only then could they be decoded. Unfortunately Fawcett never found the rock again.

While stationed in Ceylon, Fawcett married – subsequent to a classic piece of Victorian melodrama – Nina Paterson, whose father was the District Judge, Galle. Nina was born in 1870 at Kalutara in a house bordering the Indian Ocean: Brian Fawcett writes that “Through babyhood, the breaking waves sang their nocturne to her”. From 1875, Kalutara – considered the island’s best low-country sanitarium – was also home to Charles Hay Cameron, who comprised one half of the reformist Colebrooke-Cameron Commission, and his wife, the ground-breaking photographer Julia Margaret Cameron. No doubt these high-ranking families would have been acquainted.

When Nina completed her education in Scotland she returned to Ceylon to lead a privileged life. It appears she met Fawcett at a tennis party in Galle. After Fawcett proposed to Nina, his brother and three sisters told him without evidence that she had lost her virginity. He wrote to her: “You are not the pure girl I thought you to be.” The engagement was immediately called off, and Nina married the Sandhurst-trained Captain Herbert Christie Pritchard who had served with distinction in the Sudan campaign. They travelled to Alexandria where he died of an embolism due to anthrax. Apparently his dying words were, “Go and marry Fawcett! He’s the man for you.”

Fawcett, who had by then discovered his siblings’ mischief, begged Nina for her forgiveness when she returned to Ceylon, which was granted, and they were married on January 31, 1901. Almost as importantly, this was the year he joined the Royal Geographic Society, during a period when he was perfecting the surveyor’s craft in Ceylon.

Being a Theosophist, it is not surprising that Fawcett rebelled against the growth of capitalism, materialism and nationalist governments. That he had the idea of creating retreats in Amazonia and Ceylon, lands that he believed had equally ancient civilizations, was indeed a Great Scheme. Jack Fawcett was a vital part of it. His birth in Ceylon in 1903 was considered miraculous by Fawcett, who wrote in The Occult Review in February 1913:

“One morning at breakfast on the verandah [at Trincomalee] a deputation of soothsayers and Buddhists asked for an audience . . . I was told that I would become the father of a son whose appearance was minutely described, the reincarnation of an advanced spirit, and my wife and I had been especially selected . . . the child would have a mole [birthmark] on the instep of the right foot, and his toes instead of a sliding scale in size would run in pairs. He would be born on Buddha’s anniversary [Vesak], 19th May. This date was a month beyond the time anticipated. A remarkable feature about the boy, not shared by his brother or sister is a slight obliquity of the eyes.”

The date, birthmark and toes turned out as predicted. On returning to Trincomalee from the Dutch Hospital in Colombo (now the Old Dutch Hospital, where once gruesome operating theatres and pitiful wards have become up-market shops and restaurants), “crowds lined the route venerating the newborn evolved being”.

******************************

Fawcett was posted to Ireland, in 1905, where Brian was born a year later. It was in 1906 that Fawcett was asked to survey the disputed national boundaries in South America by the Royal Geographical Society. For most of the following eight years he was in Amazonia. In 1908 he traced the source of the Rio Verde in Brazil, and in 1910 made a trip to Heath River (which marks the natural border between Peru and Bolivia), also to find its source.

Following a 1913 expedition he claimed to have seen dogs with double noses. These may have been double-nosed Andean tiger hounds, a breed known in Spain as pachon navarro, which were imported as hunting dogs at the time of the Conquistadors. He also reported sighting a small cat-like dog the size of a foxhound, which was probably the Bolivian mitla, now also known as Fawcett’s cat-dog. Fawcett also had a close encounter with a mortally poisonous giant apazauca spider when getting into bed one night, but managed to shake it off before it bit him.

Fawcett framed his ideas about what he called the “Lost City of Z” based on a document – Manuscript 512 – at the National Library, Rio de Janeiro. In this manuscript a Portuguese explorer describes his visit to an ancient walled city in 1753, constructed in Grecian style, but doesn’t provide a specific location. Fawcett began to make preparations to go in quest of the city but the First World War started. He dutifully returned to England and served at Flanders in an artillery brigade despite the fact that he was nearly 50.

After the war, several years elapsed before, in 1924, Fawcett decided to retain the original objective of the expedition to find “Z”- to continue to appeal to funders – as a means of keeping hidden the real objective, the Great Scheme. Eventually, with funding from the North Atlantic Newspaper Alliance, Fawcett set off in early 1925 with just two companions, Jack, who was 22, and his friend, Raleigh Rimell, 18. (Apparently Fawcett had turned down the possibility of T. E. Lawrence accompanying him.)

Jack’s realisation of his ultimate role is evident from a letter written prior to the expedition: “I begin to look upon Ceylon as almost my own private property now, and feel quite annoyed that there are strangers laying down the law there.”

On April 20, 1925, Fawcett and his companions set off for the final phase of the expedition from Cuiaba, the capital of the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso, with two Mufuquas Indians, two horses, eight mules, and a pair of dogs. The last communication from the expedition was dated May 29, when Fawcett wrote to Nina from Dead Horse Camp “the spot where my horse died in 1920. Only his white bones remain.” And tempted fate by ending, “You need have no fear of any failure . . .”

******************************

Fawcett left instructions that if the expedition did not return, no rescue attempts should be made lest the rescuers suffer a similar fate. Nevertheless, Fawcett’s sponsors decided to undertake a search and, hopefully, rescue mission in 1928, led by Commander John Dyott, a naval officer with no knowledge of the jungle. He concluded that the expedition members had been clubbed to death by Kalapalos tribesman for offending tribal etiquette. This conclusion, deduced from sign language learned from American Western silent films, infuriated the family as Fawcett was fastidious in learning the protocol of a tribe before entering its territory.

Over the next two decades similar missions took place. Often ill-equipped and misguided, many disappeared: Williams claims that some 100 people died. In 1952, the Villa Boas brothers, who represented the interests of the Indians of the area, wished to halt the incursions. They dug up the skeleton of an Indian, claiming it was Fawcett’s, and spread the story that he and his companions, severely ill, were killed by the Kalapalos. A magazine magnate flew Brian to Brazil to inspect the skeleton. Although the teeth were intact where Fawcett wore dentures, and later analysis concluded that it was an Indian, five feet two in height (Fawcett was over six feet) the press didn’t want to lose a good story, so the Dyott myth and Villa Boas hoax endured.

There were several supposed sightings of his father that Brian claimed were unreliable in Operation Fawcett yet accepted as being probably true in the Secret Papers. The most convincing occurred in 1931, when a Swiss trapper, Stefan Rattin, reported that he had encountered an Englishman, a prisoner of a group of Indians. Although the man had not given his name, Rattin’s description of him, and the fact that he had shown his dentures and mentioned the name of a friend, Sir Ralph Paget, raised hopes that Fawcett had at last been found. But when Rattin returned to rescue the supposed Fawcett, he and two partners also disappeared.

Williams remarks: “Brian wanted to cover up all trace of his father and brother. He did not want them to be found, nor their objective discovered or posterity to know anything whatsoever.” He believed the media and the public were not ready for the facts. From his diaries it appears that Brian was guided by a female earth spirit called “M”, just as Jung had a similar relationship with “Philemon”, an elderly sage. Recognised by most cultures throughout history, it is postulated that these spirits represent a shut-off section of the brain that develops independently and then communicates with the main personality. Whatever the truth, “M” guided Brian in all key issues, especially as to how much he should reveal about his father, until his death in 1984.

******************************

There have been television programmes on the subject of Fawcett’s disappearance, such as the Russian The Curse of the Incas’ Gold/Expedition of Percy Fawcett to the Amazon, released in 2003 as part of the series Mysteries of the Century. And 2011 saw the international broadcast of PBS’s Lost in the Amazon-the Enigma of Col. Percy Fawcett, from the series Secrets of the Dead.

Inevitably there have been books dedicated to solving the mystery. Peter Fleming, brother of Ian “007” Fleming, went in search of Fawcett without success as he records in Brazilian Adventure (1933), a book often considered a classic of travel literature. With Colonel Fawcett in the Amazon Basin (1960), from the series Adventures in Geography, has a Ceylon connection as it was written by Harry Williams, a tea planter with a literary bent, who also wrote With Robert Knox in Ceylon (1964) from the same series, Twins of Ceylon (1965) from the Twins Series, and Ceylon: Pearl of the East (1950), one of my choice descriptions of the island.

More recent is David Grann’s The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon (2009). Grann, a staff writer of The New Yorker, visited the Kalapalo tribe in 2005 and claimed that it had an oral history regarding Fawcett, which related that the party had stayed at the village and then left eastwards. The Kalapalos warned that there were fierce Indians in that direction, but Fawcett did not heed the advice. On five consecutive evenings the Kalapalos observed smoke from the expedition’s campfire; then it disappeared.

Hollywood has realised the potential of such a story, for in 2008, Brad Pitt’s production company and Paramount bought the rights to Grann’s book. Pitt, needless to say, was to star as Fawcett in The Lost City of Z, and grew a straggly goatee beard like Fawcett, which puzzled the press for months until the reason was leaked. However, in late 2010 it was announced that Pitt had to withdraw from the movie to appear in World War Z (2013) -“substitute one Z for another” as one commentator wryly put it. The International Movie Database (IMDb) states (January 2013) that the project is still “under development”, which, in fickle Hollywood-speak, could mean anything.

Fawcett has had an impact on fiction as his friends included the popular writers Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Conan Doyle) and Sir Henry Rider-Haggard (H. Rider-Haggard), both of whom visited Ceylon (for an account of the former’s encounter, see my “Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: The Spiritualist in Ceylon”, The Sunday Times, April 1, 2012). Doyle based his Professor Challenger character on Fawcett, whose reports of his expedition to Huanchaca Plateau, Bolivia, became the basis of the novel The Lost World, where dinosaurs roam, originally published serially in the Strand Magazine from April to November 1912.

In Operation Fawcett the explorer (presumably) wrote: “Monsters from the dawn of man’s existence might still roam these heights unchallenged, imprisoned and protected by unscalable cliffs. So thought Conan Doyle when later in London I spoke of these hills and showed photographs of them. He mentioned an idea for a novel on Central South America and asked for information, which I told him I should be glad to supply.”

Incidentally, Fawcett has been proposed as a possible inspiration of Steven Spielberg’s archaeologist/adventurer character Indiana Jones, who has lent his name and presence to four cinematic spectaculars, one of which, coincidentally, was made in Sri Lanka. Certainly a character called “Percy Fawcett” assists Jones in the novel Indiana Jones and the Seven Veils (1991). Spielberg has often been accused of plagiarism: indeed I have written about the possibility of his having taken the idea for ET from a Satyajit Ray’s script The Alien (a project in which Mike “Ranmuthu Duwa” Wilson was involved) in my forthcoming The Wrecking. Perhaps this was an instance in which Spielberg had a real larger-than-life character to latch onto.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus