Sri Lanka’s economy after 65 years

View(s):By Chandrasena Maliyadde

Sri Lanka celebrated its 65th Independence Day in Trincomalee earlier this month with a lot of glamour and colour. The theme of this year’s celebration was ‘A Glorious Motherland – A Flourishing Tomorrow’ (Asirimath Mawubimak – Isurumath Heta Dinak).

Where is the Sri Lankan economy 65 years after independence? Sixty five years may be too short a period of time to reflect upon an economy which inherits a 2500 year history. Yet, considering the pace, degree and the nature of development taking place around us in rest of the world a period of six and half decades is not a short period.

In Central Bank Governor, Nivard Cabraal’s words, “Sri Lanka took 56 years after independence to reach $1,000 per capita income in 2004. However, from 2005 – 2011 it made remarkable progress and reached a $2,836 per capita”. Sri Lanka can boast of reaching an all time high impressive growth of over 8 per cent in 2010 and 2011. The country is already in the club of lower middle income countries. The economy demonstrates many signs such as availability (does not guarantee the affordability) of a wide range of commodities, structural changes, modernization, urbanization, super infrastructure, etc. of a high income country. The official figures show a very low and decreasing poverty ratio and an unemployment rate. There are many state run programmes to improve the infrastructure to modern standards. Seaports, airports, highways, flyovers, road rehabilitations, and multi- source electricity generation projects are all around us. Projections indicate increased numbers of tourists, FDI, export earnings, and foreign remittances. Sri Lanka combines good human and natural resources with comparatively impressive social indicators. Life expectancy is high for a developing country, and over 95 per cent of the population is literate. All the signs are pointing to a country of modernization, growth and prosperity.

Sri Lanka since independence adopted several different economic models. They range from major irrigation development (Colonization Schemes, River Valley Development) aimed at opening the dormant dry zone, industrialization, nationalization, privatization (in the guise of peoplization), mixed (capitalistic framework with a flavor of socialistic features), state managed, closed, protectionist, import substitution, structural reforms and finally tilting towards a fully open, liberalized system. The present Government is adopting a two-pronged economic development policy. At macro level infrastructure development and modernization is moving ahead at an accelerated pace. At micro level an island wide “Divineguma” programme is on course.

With all such models, efforts, wishful thinking and colossal amount of investment and foreign aid where has the Sri Lankan economy reached?

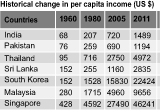

One writer in an article to a newspaper, says, “Sixty five years ago on this day, when Sri Lanka, then Ceylon, received independence, our per capita income was Rs 397 (US$ 120 then), which was on par with Japan. At that time, the per capita income of South Korea was US$ 86. Hong Kong was then, a fishing harbour. Taiwan was guarding itself from marauding Maoists.

The departing British left a flourishing economy, which then had a surplus in the trade account………… What followed the departure of the British is now history.”

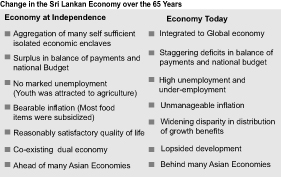

At the time of gaining independence, the country was at par or ahead of its Asian neighbors. Table 1 explains how the picture was changed over half a century.

These two tables provide a comparative picture of the economy then (at independence) and 65 years later (today). These two tables should serve an eye opener.

At the time of independence the agriculture sector accounted for more than 50 per cent of GDP. Domestic agriculture led by paddy was attractive. Over the last 65 years, expansion of access to education increased the literacy to an impressive boastful high level. The agriculture sector remains at subsistence level resorting to conventional production systems. New technology, improved seed varieties, facilities for processing, storage and marketing (post-harvest facilities) has failed to come into the agriculture sector. This has made agriculture non economical and low yielding. It is neither commercialized nor modernized. Domestic agriculture has become no longer attractive to educated youth. Plantation agriculture at the time of independence was in the hands of well organized, well managed large companies. These companies are today being replaced by the smallholder. A sizable volume of tea production today comes from this sector. Sri Lankan origin tea is world famous for its rich aroma and taste but it tends to lose its competitive edge in the world market due to the high cost of production and lack of quality check.

The challenges faced by most of the agriculture produce today are identical to that of 65 years ago. Products are not diversified; markets are not diversified; it is not commercialized; it is not modernized; it resorts to conventional production methods; arrangements for post -harvest operations and marketing are absent. It faces problems with quality, regularity, standards, high cost, low yields and inefficiency. It is still weather dependent.

Tea was the major export item at independence. It is today replaced by an industrial export-apparel product. Import content of apparel is much higher than tea. This reduces net foreign exchange earnings and value addition. At independence the economy was export led. Export earnings were higher than import expenditure. Today it has become import led. Imports are growing faster than exports resulting in a widening trade gap. Tea, rubber and coconut including coconut oil substitutes are sighted in the import list. The turn of the economy from export led to import led is symbolized from Lipton Circus down Union Place. “Lipton” is replaced by a leading automobile importing company. Famous tea export agencies such as Brook Bond, Stassen, Commercial Co. located along Union Place have been replaced by many automobile and motor accessory importing agencies. Eye catching green paddy patches along the roads have been encroached by used vehicle, motor accessory and spare parts importing firms.

Cottage industry, handlooms, ironsmiths, goldsmiths are becoming a rare sight in the presence of many imported items appearing on the waysides. Disappearance of such activities marks deprivation of a host of supplementary sources of income to the village folk, a loss of an opportunity for social gathering especially for women and a loss of an opportunity for village youths to sharpen their skills. We as children, back in the village, used to fly kites made by ourselves with whatever the materials available. On some we had our own names while on the rest our girl friends’ names were printed. Today even the kite is imported and something is scribbled on it in Chinese.

Cottage industry, handlooms, ironsmiths, goldsmiths are becoming a rare sight in the presence of many imported items appearing on the waysides. Disappearance of such activities marks deprivation of a host of supplementary sources of income to the village folk, a loss of an opportunity for social gathering especially for women and a loss of an opportunity for village youths to sharpen their skills. We as children, back in the village, used to fly kites made by ourselves with whatever the materials available. On some we had our own names while on the rest our girl friends’ names were printed. Today even the kite is imported and something is scribbled on it in Chinese.

The nation has invested heavily and pinned high hopes on education, especially at the university level. The dream of many children and parents irrespective of their social class, economic profile and location is the ‘University’. Unfortunately, universities seem to have failed to fulfill the expectations of our society. The Ministry of Higher Education is not happy; the University Grants Commission is not happy; University staff, both academic and non-academic, are not happy; industry is not happy; Parents are not happy; undergraduates are not happy; and graduates are not happy. There is hardly anyone who is happy about the present status and the outcome of the university education system.

The GDP per capita alone doesn’t tell the whole story, because it doesn’t show how wealth is distributed within a country. According to government figures, 15 per cent of Sri Lankans live below the official poverty line of Rs. 3,087 a month. The World Bank puts the figure higher, at 23 per cent. The UN estimates that 45 percent of Sri Lankans live on less than 2 dollars a day. The richest 10 per cent of the people holds nearly 40 per cent of the wealth while the poorest 10 per cent hold barely over one per cent. The Western Province still contributes nearly 50 per cent to the national income. Sri Lanka has failed to keep pace with global trends and challenges, and be responsive to our local needs. We can engage in ‘blame games’, and shield ourselves. Public servants and policymakers would blame the politician. Private sector would blame the public sector. Politicians would blame the international community. This goes in circles.

I believe that looking for a culprit (scapegoat) is not going to be helpful. We- all the people, corporate sector, banking and financial sector, public sector, policymakers and the politician should equally share the responsibility. Each successive government has contributed in different proportions to this situation. The country needs a service oriented, development inclined public service. The country needs a risk taking (rather than a risk averting) independent (rather than state dependent) corporate sector. The country needs a development banking and financial sector which is ready to share the cost (not only the benefit in adversity) with investors.

There is no point in lamenting over missing the bus. All is not lost. There cannot be a better occasion than the 65th Independence Day celebrations to reflect and take a critical look at the economy collectively as a nation and be futuristic. The recipe is not found in the past. It is in the future. We must look at the past only on a rear view mirror and move forward. We can learn lessons from past mistakes and others’ successes. We need not burn our finger; we need not reinvent the wheel.

The recipe is found in Mr. Cabraal’s statement. He remarks that Sri Lanka has to fashion the right policies to avoid this “middle-income-trap” situation in its effort to becoming a ‘Break-out Nation’. Mr. Cabraal said that there are many lessons to be learnt from empirical examples of the 103 countries……………………

(The writer is a retired civil servant)

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus