News

Halal: Food for thought

View(s):By Charundi Panagoda

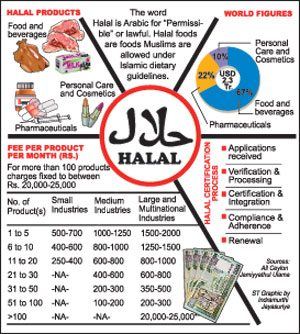

Halal, a word that has stirred much controversy and tension in the country, is simply Arabic for “permitted,” as opposed to Haram, Arabic for “prohibited.” Under Sharia Islamic law, Halal and Haram designate objects and actions permissible or sinful for Muslims.

More commonly, Halal is a term referred to food items Muslims are allowed to consume under Islamic dietary guidelines. The Quran explicitly forbids Muslims from consuming pork, blood, carrion, alcohol, meat over which God’s name has not been pronounced, animals slaughtered in the name of any other than God and animals that have been strangled or beaten to death, killed by a fall, gored to death or killed by another animal and not finished off by a human.

In order to ensure that food they consume does not contain any Haram products, Muslim communities worldwide rely on the Halal certification, including predominantly non-Muslim countries such as the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and Thailand.

In Sri Lanka, Halal certifications are provided by the All Ceylon Jamiyyathul Ulama (ACJU). Established in 1924 as a “non-political, non-governmental national religious institute,” the organisation was incorporated by Act of Parliament No. 51 in 2000. ACJU consists of over 4,000 Muslim theologians (ulamas) and “acts as the accepted authority concerning religious affairs of the [Sri Lankan Muslim] community.” ACJU services include Sharia rulings (fatwa), moonsighting (hilal), advocacy, Islamic banking and Halal certification.

According to the ACJU, Halal certification is a process of “screening” ingredients in food production with the goal of clarifying to the Muslim consumer whether the product is contaminated with any Haram material.

ACJU’s Halal Certification Committee consists of 10 theologians and eight experts from fields of science and technology. The certification is processed through five sectors — abattoir sector which applies to slaughter houses, food premises sector applicable to buildings and areas food is prepared and served such as restaurants, product sector which applies to foods processed and manufactured in Sri Lanka, endorsement sector for foods imported or re-exported and storage sector applicable to warehouses and cold rooms.

Currently, ACJU has given certificates for more than 4,500 products and about 200 organisations. In December 2006, the Consumer Affairs Authority (CAA) recognised ACJU Halal certifications in a gazette directive but rescinded that directive seven months later. On September 10, 2007, the CAA issued another gazette directive recognising Halal certificates issued by a “recognized body,” but rescinded that directive in February 2008. Chairman of the CAA Rumy Marzook refused to comment due to the sensitive nature of the issue.

Despite allegations, Halal certification from ACJU is voluntary. The organisation issues certificates only if the businesses seek it, President of ACJU M.I.M Rizwe (Mufti) said. The applicants first must submit a letter of request for certification followed by submitting the actual application. After a site investigation, if the Halal Certification Committee approves the application, a certificate will be issued with a service fee. The ACJU conducts announced or unannounced site visits periodically to maintain standards, and certificates must be periodically renewed.

Recently, ACJU has been under fire over allegations of profiteering from Halal certifications. Accusers ask ‘does the ACJU need to issue Halal certificates for everything from soaps to brushes?”

UNP MP Kabir Hashim said if there’s an issue of ACJU’s authority to issue certificates or profiteering allegations, then it’s the “government’s job” to set up a process for transparency and supervision via the Sri Lanka Standards Institute or Muslim Affairs Department.

“I think there is a big misunderstanding regarding Halal certification, it’s not forced on anybody and it’s preposterous to claim Halal certificates are ‘Islamifying’ the country,” he said. “If there are issues the state should supervise, like the predominantly Buddhist Thai government does. I believe mostly because of free market economy and globalisation, many companies need Halal certificates to access certain local and foreign markets.” While some food items can be clearly deemed Halal or Haram, some items are Makrooh, or doubtful or questionable, especially when ingredients are not listed.

For example, many bread products may contain a dough conditioner called L-Cysteine, considered Haram because L-Cysteine is mainly sourced from human hair, duck feathers or according to a manager from its Chinese production company, hog hair. As the final bakery products will not list L-Cysteine as an ingredient, ACJU says Halal certification is necessary to “assure” Muslim consumers.

How necessary Halal certification is for Muslim consumers, however, depends on individual preferences. Some Muslim consumers said their eating habits depended on ACJU Halal certification, others said they were only concerned whether meat and poultry was Halal, and the rest didn’t care either way and ate what they wanted.

Halal “only a pretext for ulterior motives”–Hakeem

Justice Minister and Leader of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress Rauf Hakeem said a recently-appointed Cabinet sub-Committee is currently holding discussions between the Muslim community and Bodu Bala Sena organisation over the Halal certification issue. Convening for the first time last Friday, Minister Hakeem said “encouragingly” both parties are willing to compromise and come to a viable solution. The Minister added that one of the possible solutions being discussed is for the government to create a mechanism to supervise certification in an acceptable manner. Also under consideration is for an accredited government institution to get involved, similar to the process in other countries.

“These are all just ideas, but at the same time we can decide if we should let the same system continue in a manner acceptable to both parties,.” Minister Hakeem said.

The Minister added that it is the “right of Muslim consumers” to consume Halal food. He said Halal certifications are being used as a “pretext,” “unfortunately and worryingly” to create “unnecessary misunderstandings that could result in violence.”

“ACJU has been subjected to all sorts of absurd probing [allegations of ‘Islamifying’ and funding foreign terrorists], this is why it appears that some kind of supremacist tendencies are developing in the country affecting harmonious relationships between communities, instigated by certain vested interests,” the Minister said.

Halal controversies are not isolated to Sri Lanka. In the past few years, right-wing politicians, media groups and even Presidential candidates in the UK, Canada, France and the US have made similar accusations of Halal “Islamifying” countries and being “secretly imposed on non-Muslims.” Some countries, like the Netherlands, have banned ritual slaughter provoking outcries from both Muslims and Jews, who have kosher guidelines similar to Halal.

Commenting on the rising Halal-phobia in France, a Muslim activist and author wrote, “I suspect it’s fear. Fear and politics. Both fear and politics operate the same way in France, conveniently blaming all French social ills on Islam. Hence, the reaction toward halal.”

What about cruelty to animals, ask activists

According to Islamic law, meat permissible for consumption is produced by a method of ritual slaughter called Dhabihah, where a butcher who is of the People of the Book (Jews, Muslims and Christians) slaughters the animal with a swift, deep incision to the throat with a sharp knife that severs the jugular veins and the carotid arteries (but leaving the spinal cord intact) so the animal dies by exsanguination, or blood loss. The butcher has to recite an Islamic prayer offering the animal to God before slaughter.

The Dhabihah method, though not without criticism, is believed by Muslims to reduce the pain felt by the animal. Animal Rights Activist Sagarika Rajakarunanayaka said, while Islamic law prescribes that an animal must be treated humanely before slaughter with food and water, these Islamic principles are often ignored by local Halal-certified butchers.

“The butchers only care about killing as many animals as speedily as possible and they do it in cruel and inhumane fashions,” she said. “They are only worried about the Halal label on the meat, not whether the prescribed laws are followed. No one, not even the Buddhist monks protesting this, is bothered about the animal cruelty aspect.”

She added that without supervision there’s no difference between religious and non-religious butchers.

Additional Director General for Livestock Development D. R. T. Rathnayaka said non-religious butchers in Sri Lanka often hammer the animal with an iron rod or use bolt guns to render animals unconscious before slaughter. “In most places, they cruelly tie down the animals and beat them to control them before slaughter,” he said.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus