News

Hundreds displaced, livelihoods destroyed in Govt. land grab for development

View(s):Never again will they return to the way of life they lived for generations only to be made extinct. Namini Wijedasa reports

The Government is taking over hundreds of acres of land in all parts of Sri Lanka, as it surges ahead with a massive development drive. Statistics from the Land Ministry’s Acquisition Division show that there were 397 requests for acquisitions in 2012. This year, there have already been 97 within two months, indicating that there will be reams more before December. Typically, each of these requests represents many hundreds of acres of land and the families that own or live on them.

People facing displacement in Uma Oya

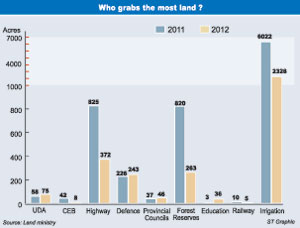

The vast majority of acquisitions are carried out for road widening, and water supply and irrigation projects. Smaller parcels are taken over for schools, playgrounds or sports grounds. The Urban Development Authority (UDA), under the Ministry of Defence, is separately snagging large extents of land within cities.

The Land Ministry says that, in 2012, the Government acquired around 3,382 acres of land. The Irrigation Ministry grabbed nearly 2,330 acres of this. The Ministry of Highways was second with 372 acres. The Forest Department acquired 263 acres, while the Ministry of Defence took 243 acres. Environmental groups say these figures are much higher.

The Ministry of Finance’s 2011 Annual Report shows that significant sums of money have been spent on acquiring land—Rs 3.8 billion in 2011. (It was Rs 3.6 billion in 2010).

Midway through each acquisition process, a gazette is published, stating that the Land Ministry has decided a particular property is to be acquired. A cursory glance at the extraordinary gazettes page of the Government Printer’s website reveals notice after notice of land being procured.

At the last count yesterday morning, there were 20 such gazettes—in just nine days. They pertained to properties in the districts of Hambantota, Colombo, Anuradhapura, Ratnapura, Ambalantota, Matara, Kandy, Nuwara Eliya, Badulla, Kurunegala, Kegalle, Badulla, Matale, Kalpitiya, Puttalam, and Galle.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that the extents grabbed are always large. It does signify, however, that there are numerous plots involving numerous parties. For instance, strips of land on either side are being acquired for the widening of the Colombo-Kandy Road. This might not lead to displacement but many families are affected.

On the contrary, ongoing giant development ventures—such as the Uma Oya Multipurpose Development Project and the Moragahakanda Project—are not only uprooting families but entire villages. The first includes the construction of a tunnel, two dams across the two main tributaries of Uma Oya, and an underground power station at Randeniya. The second envisages the building of Sri Lanka’s second largest reservoir.

While compensation, alternate agricultural land for affected farming families and homesteads have been promised, peoples’ organisations fear they will never get back their lives—or livelihoods—in the manner they had known and practised for generations. This has happened in districts such as Hambantota where the government took possession of (and continues to procure) immense stretches of land for a multitude of projects.

Encouragingly, the Government has resolved to implement the “National Involuntary Resettlement Policy” (NIRP) in the construction of Moragahakanda, said Land Ministry Secretary T. Asoka Peiris. This Asian Development Bank funded policy dates back to 2001, but hasn’t always been followed. It was implemented in full during the construction of the Southern Expressway, and minimised many of the problems faced at the initial stages. (It didn’t, however, prevent entire villages being split in two).

“For instance, the NIRP states how compensation should be paid and what entitlements people without land title have,” said Senior Research Professional at the Centre for Poverty Analysis, Nilakshi de Silva. “If you are a non-title holder, compensation is usually very basic, whereas the NIRP says that, even people without titles have a right to replacing whatever they lost in a different location.”

Agricultural lands that will be submerged under the Uma Oya project

One of the most worrying aspects of ongoing land grabs is the loss of agricultural land to development projects. The Sri Lanka Nature Group and the People’s Alliance for Right to Land, conducted a study of 25 projects, the results of which were released in June 2012. It found that, throughout Sri Lanka, a total of 36,611 hectares have been acquired through “illegal means”. “About 26,561 hectares have been seized by government institutions, while 10,050 hectares have been rewarded to the private sector,” it states. Moneragala district was the most affected. These statistics don’t always tally with official figures.

The researchers assert that the Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources Management, Sri Lanka Army, Sri Lanka Navy, Civil Defence Force (CDF) and the Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA) “are among the State institutions that engaged in land grabbing the most”. They lament that this led to the displacement of thousands of people, loss of livelihoods of fishermen and farmers, rapid depletion of forest cover and resultant hydrological and environmental impacts, and also creation and aggravation of the human-elephant conflict.

The takeover of these lands will affect food production, by depriving farmers and fishermen of their livelihoods. Many end up as labourers or in other jobs. The acquisition of agricultural land has also reduced household income among farmers. Whatever its effects, land acquisition is a reality and will continue into the future. The only way the affected could gain respite is in the Government following the best practices laid down in the NIRP.

But that policy is still fully adopted only in the case of mega projects such as the Southern Expressway and Moragahakanda. That, say campaigners, is not enough.

Where to, from here, and for what?

Every few weeks, an old man from Meemure, calls up the Land Ministry to check on compensation for a property he had lost 16 years ago. Lensuva is around 70 years of age. For generations, his family had lived and farmed on a plot in Meemure, an isolated little village tucked peacefully away in the Knuckles Range. But the mountains are a protected area. However, in 1997, the government gave notice of acquisition to Lensuva.

The tract was duly vacated on promise of compensation. It was found, however, that Lensuva did not have title to the land—a common occurrence in villages where properties are passed down through generations without corresponding transfer of documents. Worse, there was no plan for his plot. Lensuva could still have received compensation without his deed. But since the authorities were unable, among other things, to determine the boundaries to his property, money allocated to compensate him was deposited with the court. He has neither the means nor the energy to initiate legal proceedings. So he keeps calling instead.

This man’s case is just one example of how land acquisition can cause enduring anguish. Although forest reserves are protected, there are human settlements within. Villagers grow paddy and cardamom, while also engaging in chena cultivation. The Government’s intention is to acquire such lands so that the forests can be deemed as truly protected.

But how does one reconcile this with the Government’s policy of taking over lands in nature and wildlife reserves (including buffer zones) for private sector or State projects?

Sometimes, even when procedure is followed, with families being compensated and relocated, there is despondency. Take the case of 60-year-old Mapalagamage Gunawardene. Four years ago, his family was relocated from Nelumpathvila in front of the Hambantota Harbour.

For the two-and-a-half acres of land Mr. Gunawardene had farmed vegetables on, he was given 20 perches to build a house on and one acre to cultivate. But his home and his cultivation plot are located about four kilometres apart. And his village unit of 25 families that had lived and farmed together, are now split up. “I can’t farm my land because of elephants and cattle,” he told the Sunday Times by telephone. “Earlier, we all took turns to watch our lands, but we are no longer in the same location. The other families in my settlement are fisher families from Mirijjavila, and they go to sea.”

Now, says Mr. Gunawardene, more land is being taken over by the Government in Hambantota. Chena farmers, who don’t have title to land, are suffering as a result. But hotels are coming up. “What can we say or do?” he asked, observing that he works nights as a security guard. “How is the peoples’ right to development protected, through their involuntary relocation to traditional habitats of wild elephants, and with no livelihood opportunities?” asks Miyuru Gunasinghe, a researcher for Law and Society Trust, who produced a 2012 report called, ‘Mega Development Projects in Hambantota: In Whose Interest?’.

Development needs to go hand-in-hand with the protection of the rights of people, she says. “Although Hambantota may begin reaping rewards in another decade, it would have impoverished a generation of locals, whilst burdening the country with an unnecessary level of debt, unnecessary because, many of these projects are ‘white elephants’, for purposes of prestige or personal aggrandisement,” she holds.

The UDA’s actions in certain parts of the country are particularly controversial—from ejecting slum dwellers to grabbing prime commercial land from settlers in Colombo, to be doled out to foreign investors. In one recent case that attracted widespread attention, the UDA acquired a seven-acre parcel of land in Slave Island. Four acres were for the Indian TATA Housing to establish a “commercial hub” and the remainder to build a condominium to relocate the affected families.

A total of 366 families were given two months to vacate the land but the Supreme Court issued a stay order after some of them filed a Fundamental Rights application. The Court has since cleared the UDA to proceed with the project. In the next few years, as more sections of the Greater Colombo Development Plan are implemented, other lands will be taken over “for public purpose”. Lives will be disrupted, despite efforts to minimise the damage. The greater public will laud the Government’s efforts because, after all, the country needs development.

It doesn’t lessen the anguish for the uprooted people. “Really, all you need to do is stop and think, ‘If this happened to me, how would I react?’” reflected Nilakshi de Silva. “Old house, new house, it doesn’t really make that much of a difference.” “Money is better than nothing, that’s true,” she nodded. “But you can’t really get back to where you were before.”

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus