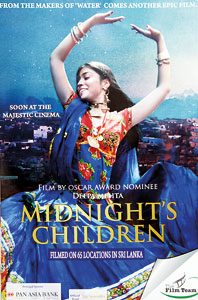

Midnight’s Children: Spotting the familiar places and faces

View(s):Midnight’s Children opens at Colombo’s Majestic Cinema on March 29.

By Smriti Daniel

A prediction: Sri Lankan fans will find it difficult to lose themselves completely in ‘Midnight’s Children,’ but perhaps not for the reasons you’d expect. For the movie, 65 locations in and around Colombo were subtly altered to masquerade as India, Bangladesh and Pakistan between the pivotal years of 1917 to 1977 and for local eyes this offers up a simple sort of pleasure – the sedentary sport of spotting the familiar places and faces.

Tough challenge: Ravindra Randeniya

There’s Ashok Ferrey the waiter carrying a tray at a party, Shanaka Amarasinghe playing a doctor with bad news and Tracy Jayasinghe manning the receptionist’s desk at a pickle factory; there’s Pasan Ranaweera and Natalya Gunaratne clustered around Saleem and Shiva and the rest of Midnight’s Children – just some of the actors in a film that cast thousands of Sri Lankan extras. There are buildings we know – the chapel at S. Thomas’ College, Mount Lavinia, the verandah of the 80 Club, the hallways of the Lady Ridgeway Hospital.

When Deepa Mehta chose to tackle the Booker of Bookers prize-winning novel she did so with the complete blessing of its iconic author – Salman Rushdie not only wrote the script for the film but helped produce it as well. To begin filming Mehta returned to Sri Lanka, the island that was her haven when she was making ‘Water,’ and to The Film Team, the production company that saw her through.

The story they were telling was that of the children born on the stroke of midnight, on the day India embraced her independence. Inextricably bound together and to the fate of their nation, we shadow Saleem, Shiva and Parvati through the decades of tumult that follow.

Reading the script of ‘Midnight’s Children’ for the first time, The Film Team’s chairman Ravindra Randeniya knew they would have their hands full. “The challenge that was before us was immense. This was a beloved novel that had won many awards,” he says of Rushdie’s book. In particular, the scenes where they would have to cope with large numbers of extras, would prove challenging. To recreate one where a marshy field in newly birthed Bangladesh was littered with corpses, they brought hundreds of locals in at three a.m. and kept them there for hours – all cold, wet and fodder for the mosquitos. To film a victory parade, they recruited an estimated 3000 extras.

In a quote released to the press, Mehta herself described what the large, multi-national cast undertook: ‘It was a long and strenuous seventy-day shoot complete with mosquitoes, elephants, escaped cobras and screaming babies, but each actor managed to inhabit their role with a sense of determination and love, drawing from the generosity of Salman’s characters.’

To create the slum where Parvati lives, the Film Team’s art director Errol Kelly built a labyrinth of flimsy buildings on a playground, complete with movable shacks that could be used to hide any evidence of modernity such as parked cars and obviously modern buildings protruding into the skyline. He then set about methodically destroying it for the cameras.

A still from the movie

Building a slum: Art director Errol Kelly inspects the set

“There were big scenes like that in the film,” says Randeniya. “Logistics wise it was very tough.” However, having pulled it off, Randeniya says the team has been fielding enquiries from foreign filmmakers wanting to make movies in Sri Lanka since. At the London premiere of ‘Midnight’s Children’, he says he was told – ‘if this movie could be made in Sri Lanka, any movie can be made in Sri Lanka.’ He hopes films like this will also bring tourists flocking to the country. “On the wide screen when the country is opened up you see vistas that never can be provided by any other medium,” he says.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus