Rejoinder to:“Do we need all these imports?”

View(s):By Dr. S.S. Colombage

I read with much interest last Sunday’s Business Times article on the above important issue, written by my long-time friend Chandrasena Maliyadde. He has articulated the adverse socioeconomic effects of the free inflow of imports, in his typical pleasing manner. In addition to the substantial foreign exchange drain, these imports cause health, safety and environmental hazards, he argues. In conclusion, the author states “I am not proposing going back to a closed economy but rationalisation of imports rather than unrestricted, unchecked imports”. While endorsing his views, what I would like to highlight here is the point that it has been the disarray of the macroeconomic fundamentals, rather than the import liberalisation per se, that has tended to accelerate imports worsening the trade balance year after year. Hence, any form of import curtailment would not be a lasting solution to deal with the foreign exchange imbalances.

(Macroeconomic fundamentals)

I am rather hesitant to find fault with the bold trade liberalization polices that were launched in 1977, though the sequencing of the process may be debatable. The trade liberalisation was a key component of the wide structural reform policy package introduced by the then government in the anticipation to resuscitate the country from a severe economic stagnation manifested by stringent administrative controls imposed by the pre-1977 political regime, in line with the similar type of inward-looking policies adopted by many other developing countries during that time. Following the reforms, administrative barriers on imports were removed, and price controls on many consumer goods were abandoned. These deregulations were vital to permit resource allocation among different sectors to be determined by market forces rather than by administrative controls of the government, and thereby to pursue an outward-looking economic policy strategy.

Theoretically and empirically, it has been well established worldwide that administrative controls will only create market distortions plunging countries into long economic depressions. In addition to the prices of goods and services, interest rates and exchanges rates, which are the prices in the money market and foreign exchange market, respectively, are allowed to be determined by market forces in a liberalized economy. All these prices are instrumental in allocating resources. Movements in these prices in response to market demand and supply conditions drive an economy to the equilibrium levels.

Consumers allocate their expenditure between non-tradable goods (produced at home and cannot be traded abroad) and tradable goods (those can be traded in international markets). The relative price of non-tradable goods in terms of tradable goods, the inverse of what is commonly known as the real exchange rate, is by far, the most important market instrument in maintaining the external balance. For example, a depreciation of the domestic currency shifts the relative prices in favour of tradable goods thus encouraging exports and discouraging imports, and in turn, resulting in a lower trade deficit. Prudent fiscal and monetary policies are also essential to support the balance of payments adjustment process driven by flexible exchange rates. For instance, monetary expansions led by persistent budget deficits cause domestic demand to move upwards raising the prices of non-tradables relative to tradables. Such a policy stance induces imports due to lower prices of imported goods relative to non-tradables. Meanwhile, exporters would be disillusioned by an appreciation of the real exchange rate caused by high domestic inflation.

(Twin deficits)

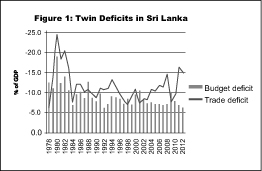

The link between the budget deficit and trade deficit is well-known, and they are known as ‘twin deficits’ in the literature due to their intimate relationship. The proponents of the twin deficits hypothesis assert that an increase in the budget deficit leads to an increase in the trade deficit, and therefore, fiscal consolidation is essential to reduce the trade deficit. Following the emergence of the budget and current account deficits in the US and in many other countries in the 1980s, the relationship between the two deficits attracted the attention of policy makers and researchers worldwide. A budget deficit could worsen the trade deficit through different channels. One such way is an appreciation of the exchange rate due to accumulation of external assets through foreign borrowings by the government. High government spending may also lead to an increase in aggregate demand causing a surge of imports. Monetary expansion led by deficit financing is another way that could propel the demand for imports.

Sri Lanka had experienced budget and current account deficits continuously since the late 1950s in the pre-liberalisation period. The deficits continued in the post-liberalisation as well reflecting a close association between them (Figure 1). The concerted efforts made by the successive governments during the last two decades for fiscal consolidation helped to contain the budget deficit ratio to a single digit level. However, fiscal imbalances remain a major challenge in macroeconomic management. The budget deficit rose to almost 10 per cent of GDP in 2009, and it declined gradually to around 7 per cent by 2011. The trade account deficit rose to 16.2 per cent of GDP in 2011 reversing the favourable trend experienced in the previous two years. As announced by the Central Bank recently in its policy document, Road Map for 2013 and Beyond, it is envisaged to reduce the budget deficit from 6.2 percent of GDP in 2012 to 4.7 percent by 2015. The trade deficit is expected to decline from 15.1 percent of GDP in 2012 to 12.7 percent by 2015.

(Dutch disease)

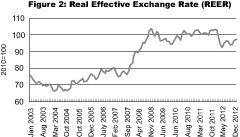

As pointed out earlier, the real exchange rate is instrumental in influencing the resource allocation between tradable and non-tradable goods. A major macroeconomic effect associated with the foreign borrowings coupled with the substantial inflows of inward remittances is the rise in the country’s international reserve stock and a consequent appreciation of the domestic currency. Such an appreciation of the real exchange rate due to exogenous factors leads to weaken the country’s export competitiveness, reflecting the symptoms of the ‘Dutch disease’. The term ‘Dutch disease’ has its origins in the Netherlands when that country’s export competitiveness eroded due to an appreciation of the exchange rate following the discovery of natural gas during the 1960s. As a result of the appreciation of the domestic currency, the relative prices of non-tradable goods rose against the tradable goods. This led to a shift of resources from the tradable sector to the non-tradable sector leading to an erosion of the country’s export  competitiveness.

competitiveness.

Sri Lanka has been experiencing a similar kind of Dutch disease in recent years, as the build-up of foreign reserves through exogenous factors, mainly workers’ remittances and foreign borrowings, led to an appreciation of the real exchange rate, and resulted in a decline in the relative prices of tradable goods against non-tradable goods. The nominal exchange rate, which was around Rs. 114 a dollar in the beginning of 2010, began to appreciate since the second quarter of that year. By mid-2011 it reached around Rs. 110 a dollar. Reversing this trend, the rupee showed signs of depreciation since the end of 2011, and reached record levels of around Rs. 120 subsequently following a decision of the Central Bank to reduce its intervention in the foreign exchange market. The Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) index rose from 77 in the beginning of 2005 to 103 by the end of 2011 reflecting a real appreciation of rupee (Figure 2). The exchange rate appreciation occurred in contrast to the worsening of the trade balance: the trade deficit almost doubled from US$ 4.9 billion in 2010 to nearly $9 billion in 2011. Around 50 per cent of this large deficit was covered by the inflows of workers’ remittances which amounted to $4.6 billion in 2011.

(Policy options)

Fiscal consolidation and structural reforms are essential for robust economic growth, as reiterated by the IMF mission which concluded its 2013 Article IV Consultations recently. In the view of the mission, policy measures are needed to broaden the government’s revenue base and strengthen administration to support fiscal consolidation, which would otherwise rely too much on reductions in spending, especially capital spending, which would have the potential to undermine medium-term growth. The mission emphasises that lowering of inflation and structural reforms are needed to enhance the country’s productivity and competitiveness so as to support robust growth over the medium term.

Sri Lanka has been over-depending on worker remittances which now amount to nearly 10 per cent of GDP. These remittances have helped to mitigate the adverse impact of the trade deficit on the current account of the balance of payments. They not only helped to contain the balance of payments deficits, but also to boost the country’s national savings thereby contributing to foster economic growth. Nevertheless, overdependence on remittances has brought about adverse economic repercussions, as pointed out earlier. In particular, they have led to a disarray of macroeconomic fundamentals. The appreciation of the real exchange rate for a long time leading to a deterioration of export competitiveness is a point in case. A more flexible exchange rate regime would have arrested the surge in imports and the resulting trade deficits. A coherent macroeconomic policy framework remains to be most plausible option available to transform the economy from the present remittance-dependent status to an export-driven status, as envisaged three and a half decades ago.

(The writer is a former Central banker, economist and academic)

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus