Appealing to the imagination, even more than the palate

View(s):Deloraine Brohier has given us a work of art that is of far greater value than if it were only just another cookery book containing Dutch and Portuguese recipes. She, together with the collaborators who assisted her in its production, have created a thing of beauty. She gratefully acknowledges her indebtedness to the many gifted people who readily gave of their expertise – notably Nelun Harasgama Nadarajah who has captured the essence of the book in the excellence of her overall design and layout, Lakshmanan Nadarajah whose photographs undoubtedly add lustre to it, illustrators Sujith Kumara and Aruna Srinath for the delicate and delightful wash drawings on which the reader’s eye lingers, and several others – like Asiff Hussein and Asgar Hussein – whose contribution to the finished work was invaluable. Neptune Publications which gladly undertook to publish the manuscript have amply justified Deloraine’s confidence in them.

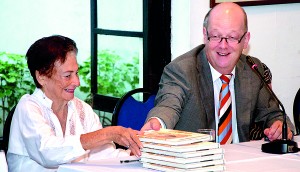

At the book launch: Deloraine Brohier (left) with chief guest Dutch ambassador Louis W.M. Piet. Pic by Indika Handuwela

And now to the book itself. Deloraine thoughtfully provides a backdrop that gives us her community’s history and their life-style in the colonial era. This is very helpful today when the Burgher presence in Sri Lanka has, sadly, dwindled to such an extent that the present generation knows little about their special gifts and graces which adorned the colourful fabric of Sri Lankan society in happier times. It was Deloraine’s discovery in her father’s library of a yellowing old manuscript entitled: “Rare recipes of a Huisvrouvw of 1770”, that inspired this volume. However, it was a long time germinating in her mind and it was through the constant urging and encouragement of an old friend, Asiff Hussein, a writer kindred spirit, that the book gradually took shape.

The 1770 MS is referred to throughout as the `Brohier Manuscript’. `Granny Brohier’ was the acknowledged expert in the kitchen, but Deloraine imbibed from her own mother to whom the book is dedicated, the art of fine dining and entertaining in grand Dutch Burgher style. After giving us the true sources of a rich variety of familiar foods and drinks, Deloraine takes us on a guided tour of both routine meals and of special occasions in Burgher homes.

Elaborate everyday meals – sumptuous Sunday lunches, delectable “tiffins” produced and presided over by Granny Brohier; the very satisfying early supper which generally started with a soup (beef, fish or vegetable), and might be followed by a main meal chosen from a variety of possible menus – seer fish prepared according to a Dutch recipe, or a Portuguese meat stew, or perhaps stringhoppers, (laterias as the Dutch called them), taken with a Dutch specialty in the form of a thick chicken and cabbage soup, our own pol sambol and seeni sambol, and egg ruling which might be described as a Dutch version of the English scrambled egg. These delicacies are only a few of many enticing foods for which recipes are given.

There are accounts of the distinctive birthday parties given by the Burghers and the two traditional Dutch Burgher celebrations held in December. The first of these was the singularly Dutch event known throughout Holland as the `Sint Nicholas Fete’, celebrated in Colombo at the DBU on December 5. St. Nicholas, unlike his universally-known counterpart Santa Claus, came attired in the full regalia of a Bishop and he made an impressive entry as he rode in astride a tall white horse to distribute presents to the children. The run-up to Christmas was full of excitement, with carol-singing aplenty from house to house, and other cherished rituals.

Every Burgher home was redolent with the inviting aroma of good cooking emanating from the kitchen, in preparation for Christmas Day. Deloraine writes that ‘Christmas was the happiest occasion in the Burgher calendar’ and she recounts her nostalgic memories of this season as celebrated in her own parental home.

I noted with some surprise that breakfast is dismissed with only a mention of a ‘light breakfast’ on Sundays prior to setting out for church. I imagined that people with such a penchant for good eating would have enjoyed the kind of hearty breakfast relished by the British of colonial times. Deloraine enlightens us about the origin of many dishes which we might loosely term as Dutch or even as Sri Lankan. She makes it clear that the Portuguese left a lasting legacy in the culinary line, adopted by the Dutch rulers who succeeded them, sometimes with variations of their own. She points out that because of its central position on the main sea-routes, Ceylon attracted seafarers even before the colonial era – Arabs, Indians and Malays amongst others.

The Arabs, for example, evidently brought in a sweetmeat they called `halwa’, which evolved into the Sinhala `aluva’. South India gave us the ever-popular appa or hoppers and also our pittu. Bibbikan, Deloraine surmises, was Malay in origin and the delicious Malay dessert watalappan, was brought to us by the colonial Dutch who, with their fine instinct for good food, did not hesitate to adopt desirable items from the menus of the native people they ruled in various parts of the East. One such item that has retained its appeal to our palates is the lamprais, that rich mixture of savoury rice packed with various tasty adjuncts and wrapped in the plantain leaf before baking – something which the Burghers of today are still the acknowledged experts of. The incomparable Love Cake came to us from the Portuguese who called it Bolo d’Amor, later anglicised by the British into the familiar label of Love Cake. The Breudher which appears on many a Sri Lankan table besides those of our Burgher friends on Christmas morning, evidently came from Flanders in Northern Belgium. I was intrigued to find that our Sri Lankan term, “temperadu’ by which we mean tempering a dish with onions, garlic, mustard etc .to make it more appetising, was introduced by the Portuguese who called it temperado, which in turn came from the Latin word tempera `to mix’.

As to the recipes, they are mouth-watering! The quantities too are staggering Read this description of a favourite Portuguese sweet, fougetti, which always figured prominently at birthday parties. It was “a pastry roll wrapped in a crystallized sugar coating and stuffed with pumpkin preserve and minced cashew nuts and delightfully flavoured with either the essence of rose water and painted pink, or with almond and painted green.” Aaah! The recipe for Love Cake mentions 200 cashew nuts and 12 eggs besides the other ingredients. For Breudher, 30 eggs were the norm, with three lbs. of flour. Most of these recipes are taken from the Brohier Manuscript of 1770. The recipe for what we call Milk Wine gives six bottles of arrack, four bottles milk, three lbs sugar made into a syrup with one bottle of water, eight ripe lemons and some spice and this would make a dozen quart bottles. Those were the days!

Deloraine brings in an endearing personal touch in describing life in the Brohier household when she was a child. Those were spacious days in a more leisurely era long before women’s lib had been thought of and women – Burgher housewives, most certainly – found full satisfaction in reigning over their homes and particularly their kitchens, albeit with an army of trained helpers. Deloraine’s father was the renowned Dr. R.L. Brohier, doyen of the Survey Department from British times to the post-independence years, whose many authoritative books on the Ceylon he knew so well remain an invaluable and enduring legacy for all time.

Deloraine lost her mother when she was only 15 years old. She was her father’s companion, chatelaine and support to the end. Her daily interaction with him and her constant browsing through his formidable collection of books, no doubt gave her the remarkable store of knowledge she has garnered both about her country and about the valued contribution made by her forbears – a contribution that goes far beyond the welcome additions they made to our diet.

I would say that Deloraine Brohier epitomises all that the name “Dutch Burgher” conjured up in bygone times and all that made them such an asset to our country. Thank you, Deloraine, for choosing to remain in your land of birth and continuing to enrich us thereby.

| Book facts

A Taste Of Sugar and Spice – Cuisine of the Dutch Burgher Huisvrouw in Olde Ceylon by Deloraine Brohier. Neptune Publications (Pvt.) Ltd. Price: Rs. 3,400/- available at the Dutch Burgher Union and at reputed bookshops. Reviewed by Anne Abayasekara |

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus