Protecting a memory and nature

View(s):An auditorium built by the parents of the late Dr.Ravindra Samarasinha, a conservationist and humanist, in the jungles of Yala that he loved so much, is sadly underutilised

By Smriti Daniel

When Derrick and Vivina Samarasinha remember their son Ravi’s funeral, they remember the number of total strangers who came. “We didn’t know who these people were, there were busloads,” says Mrs. Samarasinha. A rough count put them at over a 1000, including humble elderly villagers from Tissamaharama.

Their presence and genuine sorrow that day comforted his grieving family and made it clear to them that Dr. Ravindra Samarasinha would be remembered not only as one of the country’s most genuinely dedicated and clever conservationists but a quiet and generous humanitarian. As the months passed, they realised they wanted to create a solid monument to him, and one park seemed the inevitable choice of location. “We wanted to do something in Yala after Ravi’s death because he more or less lived there, you see,” Mr. Samarasinha says. His mother wanted to put up a building in which people could live and conduct research in the park but they ended up building an auditorium designed by architect Ashley de Vos instead, along with new ticket counters – the first stop for visitors coming into the park.

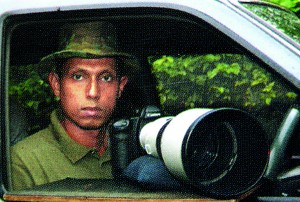

Dr. Ravi Samarasinha

On the table in front of us is a file Mr. Samarasinha filled with all the articles that were published to honour Ravi’s memory. Killed in a collision with a sand-filled lorry on a road close to his parents’ estate in 2007, Ravi was only 44 when he died. A quiet and thoughtful child, he grew up loving the outdoors, never happier than with his dogs or out exploring a new landscape. Eventually, he would study medicine and go to Kuliyapitiya for his internship before asking for a posting to Hambantota, just so he could be near the jungles he so loved.

It was during that time that he became involved in the BBC’s documentary ‘The Leopard Hunters’. The authorities only agreed to allow the team into the park after dark when Ravi assured them he would accompany the crew. “He was working in the hospital then and he couldn’t get leave,” says Mrs. Samarasinha. Ravi’s solution was to pull back-to-back shifts and then rush straight off for a night’s filming. So perhaps it didn’t come as such a surprise to his parents when he told them he wanted to dedicate all his time to his work in the wild.

“We weren’t so happy about him taking a break from medicine because I always felt he was a very good diagnostician,” confesses Mrs. Samarasinha, who only allowed herself to be convinced when her son said to her, “Let me take a break. Even if I have ten years of happiness in doing what I really like, then my life is well spent.”

Ravi was happiest in Yala. He would camp out for days, with only a tracker, a driver and his camera for company. “Sometimes it’s just the love of being there, it doesn’t matter if you don’t see anything, if all you hear is calls in the night. He was that kind of man, a genuine

![IMG_1588[1]](http://www.sundaytimes.lk/130317/uploads/IMG_15881-300x176.jpg)

The auditorium built in Ravi’s memory at Yala

Having bought the best equipment he could afford from Singapore, Ravi took an estimated 10,000 images of leopards, elephants and deer; of birds in flight and reptiles in the undergrowth, he took pictures of insects and close ups of flowers and fruit. As with his other interests, Ravi applied a meticulous, exhaustive approach to mastering photography and it was through the lens of his camera that he first began to gather evidence for what would be a ground-breaking approach to identifying leopards – the pattern of their spots was unique to each, observed Ravi, and it was that insight that would help the authorities first count and them keep track of individual animals.

Ravi would co-author or author several books and his pictures would appear in numerous publications. (When she finally brought herself to open up his flat after a year, his mother found that he was working on another and had his content meticulously organised.) He also took a very pragmatic, hands on approach to conservation. When villagers complained of having their cattle taken by leopards, he worked with other likeminded people to design traps that could be used to capture the big cats without harming them. He

|

|

| Ravi’s parents: Vivina and Derrick Samarasinha |

|

also helped build and distribute solid cages in which villagers could pen their cattle up at night, safe from hungry predators. “Ravi listened to people,” says his mother, explaining that he would often visit villages with his medicine case, treating simple ailments, doling out medicines and directing the more serious cases toward local hospitals. “People knew he was genuine because he had given up a lucrative medical practice to be there.”

Whenever he could, Ravi liked to speak to children in the local schools, firmly convinced that it would take the young to carry the conservation message. It’s why the simple auditorium seems like the perfect tribute. His parents want the auditorium to be used to screen films, host lectures and display information about the leopard and the other inhabitants of the park. Caryll says it would be ideal if this became a compulsory stop for visitors to the park.

“We want to educate the young people that it’s not just a pleasure trip. If they don’t look after this, we’ll lose it,” says Mrs. Samarasinha. Their only great disappointment, says Mr. Samarasinha, is that despite being opened with some hoopla, the auditorium is not being put to its designated use. His entreaties to the authorities have been ignored and they seem uncertain of the way forward. The one thing the Samarasinhas know is that Ravi would have wanted them to continue trying to inspire young people. “It’s important to teach children to love animals, they are the ones that will have wonderful new ideas, ideas for conservation that we haven’t even thought off,” says Mrs. Samarasinha. She knows if Ravi were alive, he would be in the forefront of the fight to save the nation’s parks. “He would be doing, not just talking.”

As we get ready to leave, Mr. Samarasinha urges us to read something Ravi once wrote in a book he was gifting to a young girl. He feels it sums up his son perfectly. “It is a gift to have a beautiful mind that can admire nature,” Ravi wrote, “but it is a greater gift to have a heart that wants to protect it.”

| Leopards: The FutureBy Ravi Samarasinha

In Sri Lanka, the greatest threat to the leopard comes from the habitat loss and fragmentation, as land requirements grow with the demands of an ever increasing population. Despite legal protection, leopards are still killed for their skin, poisoned when they kill domestic cattle and accidentally ensnared in wire traps meant for deer and other ‘game.’ The large-scale trade in game meat reduces prey densities in reserves and parks, forcing leopards to prey on dogs and cattle outside protected areas, leading to an increased confrontation with man, a conflict in which the leopard is the ultimate loser. Long-term successful conservation of the leopard requires a multi-pronged approach. The national parks, the last future stronghold of the leopard, need to be linked by corridors, ensuring genetic flow, while laws protecting the leopard and its habitat need to be strengthened and revised. The Department of Wildlife Conservation, which has been entrusted with the solemn duty of protecting the wildlife of this country, badly needs more funds and staff, but more importantly, new vision and commitment when fulfilling its duties. The leopard is a keystone species; its well being is an indication that the ecosystem that we live and depend on is thriving. We, therefore, must strive hard to conserve the leopard. If we fail, the forests and jungles of Sri Lanka will surely be the poorer for the loss of this most perfect of big cats, beautiful in appearance and graceful in its movement. (From Wilds of Lanka, by Ravi Samarasinha and Chitral Jayatilake) |

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus