The people and a way of life back then

View(s):“Pathegama (‘low-lying’ village in Sinhala), which I have chosen to write about was my birthplace. Those days, it was a sparsely populated simple village whose people were so dirt poor that they could hardly afford to possess anything resembling a modest luxury. Buddhism had taught them that excessive craving (‘tanha’) was one of the major interdependent factors that engendered sorrow (‘dukkha’). They had very little, yet they were content.”

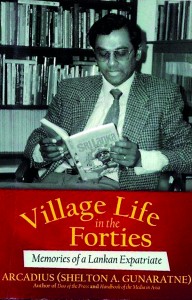

This is how journalist turned academic, Shelton Gunaratne starts discussing ‘the good old days’, as we are used to saying when we refer to the times when we oldies were young. ‘Village Life in the Forties’ is the title of a book he has authored qualifying it as ‘Memories of a Lankan Expatriate’. Having been a journalist at Lake House, Shelton moved to the United States for higher studies in the mid-1960s, obtained a doctorate in mass communication and decided on a teaching career at the Minnesota State University. Now in retirement, the much-travelled Professor Emeritus lives in Moorhead, Minnesota.

Reading through the 26 biographical sketches written in simple, readable style, I was reminded of my life in the same era. Mine was a village in the Western province while Shelton’s was one in the south. Yet there was hardly any difference in the behavioural patterns and lifestyles of the people. Possibly the only difference was in some of the words used in daily life.

One could find the characters described in Shelton’s narrative anywhere. Apart from the parents, we had the Loku maamas and the Punchi Ammas, Nendas and Bappas. There was the odd ‘Ratagiya Mahattayas’ – a rare breed who had the guts to go abroad particularly with a war (World War II) raging in several countries at the time. The ‘Vel Vidane’, who has been identified as the ‘irrigation headman’ wielded power and influence in every village and as the writer describes “was more self sufficient in the commodity (paddy) in a particular sense – not the result of his farming skills involving his own labour, but rather the result of his astonishing skills in applying his Machiavellian cunning to extract a larger share of the paddy yield each season than what each farmer legally owed him.” He sums up that his self-sufficiency so achieved was “entirely a matter of cunning.”

The writer’s skill is also apparent in the way he is able to get the reader to picture a situation in his mind. To quote an example: “During the harvesting season, I often used to go to Muittettuwa to watch the proceedings of reaping, threshing, and measuring. Women who tucked up their clothes reaped the standing corn with their sickles. They stacked the sheaved reaps of corn in the rickyard. Bare-bodied men in their span cloths threshed the corn by holding on to a pole wand and twisting the sheaves with their feet. Then the corn separated from the straw was winnowed to remove the chaff. Now the paddy was ready for measuring.”

Now with the Southern Expressway, Matara is just a little more than two hours from Colombo. Then it wasdifferent. The villagers had only heard of Colombo. Not many had seen or gone to Colombo. They could only imagine what Colombo looked like by hearing fairy tales like stories from those who had been there. As Shelton points out, the one who had physical contact with Colombo always found a ready audience at any time or place. “The braggart would recount his city adventures with utmost relish and often add colour to his stories with a flourish of the hand and an aside such as, ‘You see, the sky over Colombo is not blue – rather red and very fascinating’”. The innocent villagers believed him.

Shelton identifies the colourful court jester Andare as one who served during the reign of the 18th century Kandyan king Rajadhi Rajasinghe. He introduces Kambura – the toddy tapper in the village with one of Andare’s stories. “As I lay on the rush mat one morning, still feeling sleepy, I looked through the window, and I saw Kambura crossing from one tree to another and hanging on to the connecting ropes between them. He walked on the lower rope, holding the upper rope with the right hand without the slightest fear. I began to think of him as an expert funambulist who, considering his daring, should have got a job in a circus in Colombo.”

As was noted in the opening chapter, Shelton describes in a meaningful manner what Buddhism meant to the villagers. “As a community of very devout Theravada Buddhists, the simple folk of Pathegama professed to follow the pure Hinayana (lower wheel) form of the doctrine that the Gautama Buddha meticulously elucidated in the sacred ‘sutta’ (the Pali discourses he delivered after Enlightenment) that, together with the ‘vinaya’ (disciplinary code for monks) and ‘abidhamma’ (the latter commentaries on what the Buddha taught), constitute the ‘Tripitaka’ (three baskets). However, in truth, most villagers would have been hard put to accurately explain the Four Noble Truths as the gist of Buddhism: that ‘samsara’ (wheel of existence) is conterminous with ‘dukkha’ (suffering/sorrow), that the dependent variables encompassing ‘tanha’ (greed/craving) are the cause of this ‘dukkha’, that the way to end this suffering is to escape the ‘samsara’ and that the way to do so is by following the Exalted Eightfold Path.”

Unlike today when the avenues for villagers to listen to Dhamma sermons and participate in meritorious deeds are so varied, then the only avenue of listening to a sermon was when the monk of the village temple preached on Full Moon Poya day. As Shelton points out, the villagers invariably repeated the five precepts at every religious gathering, as well as a daily routine at home, perhaps with only a faint idea of what the Pali stanzas meant. The gap between the Dhamma and its practice was far too wide.

The writer goes on to discuss numerous village characters in the pre-Independence era in a manner that local as well as foreign readers will find it interesting reading. He has succeeded in that effort.

Shelton’s book is one of a trilogy of his autobiography published last year. The other two carry the title ‘From Village Boy to Global Citizen’ with the first volume focusing on his life journey and the other on his travels.

The book is available for purchase online through amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, xlibris.com,xlbris.com> and <iUniverse.com>.

| Book facts

Village Life in the Forties ‘Memories of a Lankan Expatriate’ by Shelton Gunaratne. Reviewed by D.C. Ranatunga |

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus