A 1695 dictionary comes to light

View(s):Dutch expert Dr. K.D. Paranavitana turns back the pages of time as he discusses the laborious task of editing ‘The Dutch and Sinhalese Dictionary’ authored by Dutch clergyman Simon Cat

By Kumudini Hettiarachchi

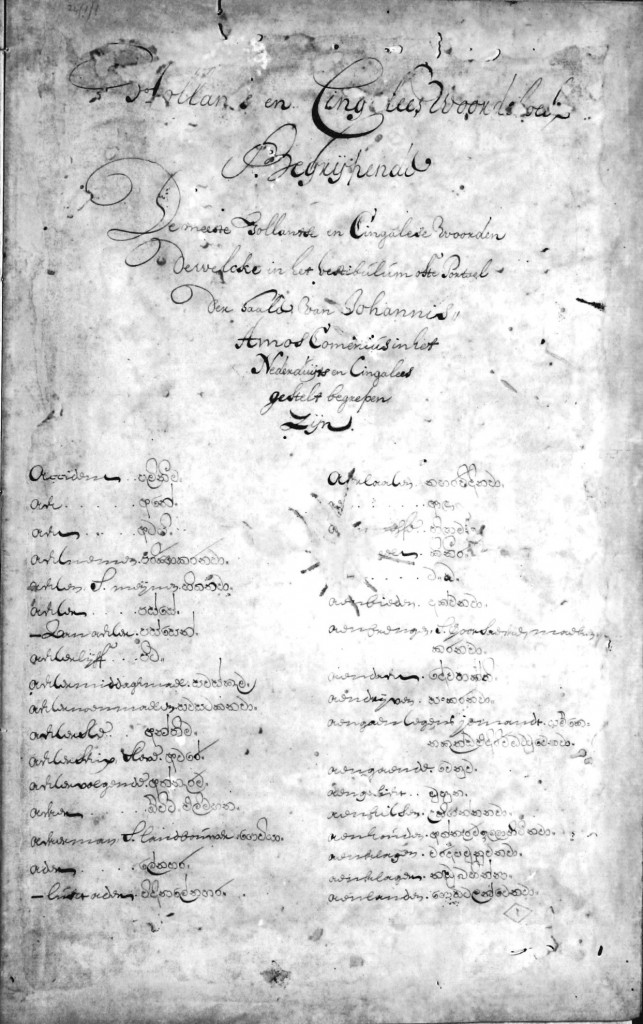

First page of Cat’s manuscript Dictionary

He came, he saw, he taught and left an indelible legacy that still inextricably links his country and Sri Lanka. Not for him a dangerous and harmful weapon….instead wielding the pen he has attempted to bring together the subjugator and the subjugated through the power of words.

He was none other than Dutch clergyman Simon Cat and his work an invaluable insight to our history which has lasted down the centuries is ‘The Dutch and Sinhalese Dictionary’.

Hidden from the public eye on a shelf of the National Archives since 1949 and earlier collecting dust in an almirah of the Wolvendaal Church in Colombo, it is only recently that the laborious and tedious work that Cat undertook in 1695 has come to light.

Published by the Department of National Archives, Sri Lanka, under the Netherlands-Sri Lanka Mutual Cultural Heritage Project, it is Dutch expert Dr. K.D. Paranavitana, with the encouragement of Director Dr. Saroja Wettasinghe, who has edited ‘The Dutch Sinhala Dictionary’, the text of which has been vetted by Gerad Simons. The Sri Lanka-Dutch partnership is to preserve, conserve and publicise Dutch records deposited at the National Archives.

For many a long year Dr. Paranavitana has been awaiting this opportunity, from the time he joined the National Archives in 1973, not forgetting this task even when he moved away for a stint as Professor of Humanities of the Rajarata University from 1996 until his retirement in 2010.

“At that time I just didn’t have the required knowledge to interpret it. So it lay dormant for quite some time,” says Dr. Paranavitana, recalling those early days when then National Archives Director A. Devaraja wanted to entrust the task to him.

Feeling he didn’t have the expertise, he started “copying” the whole text, the Dutch-Sinhala word-to-word. Dr. Paranavitana who had been dabbling in the Dutch period felt capable enough to deal with the text only after securing a Diploma in 1978 having worked at The Hague National Archives in the Netherlands.

“After training in 17th and 18th century Dutch, I felt that it helped extensively when it came to understanding the calligraphy, abbreviations and script,” he says.

It was then that he re-looked at the original Dictionary consisting of 65 bound folios of hand-made paper of the size of 35X20cm with 4,384 Dutch words and phrases written on the left hand column and the Sinhalese meaning on the right hand column. The watermark and the orthography confirm that the document probably belongs to the late 17th century.

The background flows forth – the compilation of the Dictionary which began in 1695 was completed in 1697, making Cat the first Sinhalese lexicographer. Having engaged in translating the Scripture into Sinhalese, not-so-young Cat undertook the Dictionary, mainly to propagate the religion of the foreign rulers while also meeting the all-important official requirement of communicating with the locals along the coastal belt from Colombo to Galle which was under the Dutch.

“Language was very important then as it is now,” points out Dr. Paranavitana, explaining that the language in the coastal areas was different to what was existing then in the Kandyan areas.

So to communicate, the Dutch went back to the tried and tested method known to them. “No other method was known to them except the education method which was espoused and introduced by the reputed contemporary educationist, Joannes Amos Comenius.

Digressing to charter the path of Comenius, Dr. Paranavitana says that born in Moravia (now Czechoslovakia) he was a pioneer in linguistic studies in Poland but crossed over to the Netherlands in the last years of his life to reside in Amsterdam. Although he never

Dr. Paranavitana

visited Sri Lanka, those in the Dutch East India Company knew him and it was natural that when Cat was compiling the Dictionary he followed the method of Comenius, as he was a teacher and organiser of practical educational activities using vocabulary.

Cat espoused not only Comenius’s belief that the first learning of a foreign language should be through the vernacular itself but also held his elementary text ‘Vestibulum’ in such high regard that he gave it a prominent place on the title page of his own Dictionary, points out Dr. Paranavitana.

It was also Cat, born in Zaandam in 1624 on the outskirts of Amsterdam, who translated the Bible into Sinhala, he says, sketching Cat as a “predicant” employed and paid by the Dutch East India Company. He arrived in then Ceylon as the 46-year-old Chaplain of a ship, using Colombo as his base thereafter and living here upto his death in 1704.

Twenty years after his arrival in the country, by 1690, multilinguist Cat who was fluent in his mother tongue Dutch as well as Latin, Greek and French, had mastered not only Sinhalese but also Tamil to be able to teach, preach and translate the tenets of Christianity. He had held the view that “Sinhalese is not dull and unteachable”.

Although Cat was ailing and burdened with the onerous duties of the Rector of the seminary in Colombo, he laboured on with the compilation of the Dictionary. But life was not easy for him, because Joannes Ruell who had been propelled into the role of Rector, ousting Cat pinpointed shortcomings in Cat’s translations. The matter was so embroiled in controversy that an Inquiry Committee was appointed, only to make certain recommendations to then Governor Gerrit de Heere who took the drastic decision of cutting the pay of Cat by half. It was a disillusioned Cat, while appealing to both the Governor and the authorities in the Netherlands, who doggedly persisted with his work on the Dictionary and many other translations as well.

With local learned informants hard to find to help in the language project due to unrest in the maritime areas, it was to interpreters that Cat turned who included Sinhalese, Mesticos (offspring of a European father and a local mother) and Toepases (one who knows two languages). Others who helped him included Ambanvela Rala, the leader of the Nilambe revolt against King Rajasingha II of Kandy, who fled to Colombo.

The Dictionary was finally submitted to the Governor on October 24, 1697 along with several other translations with the Chief Clerk of Colombo, Joannes Boucart, attesting the works at the Colombo Secretariat on March 23, 1698 by placing his signature and official wax seal on them.

“The copies of the manuscript had been preserved at the Wolvendaal Church until 1757,” says Dr. Paranavitana, pointing out however that the authorship of the Dictionary had erroneously been attributed to Comenius. “There is no evidence that Comenius ever visited Ceylon,” he adds.

While explaining that within the past two years he has also put out the ‘Digest of Resolutions of the Dutch Political Council, Colombo, 1644-1796’ and the ‘Alphabetical Index to the Registers of Marriages at the Dutch Reformed Church, Wolvendaal, Colombo, 1709-1936 AD’, Dr. Paranavitana adds that all the Dutch Thombus of the Kalutara district comprising family and land records have also been translated into Sinhalese, yielding some very interesting information.

The Digest compiled by the first Government Archivist in Sri Lanka, R.G. Anthonisz, way back in 1900, Dr. Paranavitana has taken under his expert care editing it, while the Alphabetical Index compiled by S.A.W. Mottau he has touched up by writing an introduction and arranging it for printing.

Dr. Paranavitana easily reverts to his most recent passion, ‘The Dutch and Sinhalese Dictionary’ and remembers with a smile, poring over both the original manuscripts and photocopies, reading and re-reading the curly handwriting on numerous occasions to get it right.

Like Cat who has left an unforgettable imprint in the form of the Dictionary, Dr. Paranavitana has also contributed his mite towards recreating the nuances of a bygone but important era which has enriched the history of this nation.

| Chonde and other words

Talk of a ‘chonde’ and both in Sri Lanka and the Netherlands will people immediately comprehend what it is, a hair-knot. |

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus