What’s the buzz?

View(s):Smriti Daniel on the work of Sean Borodale, considered one of Britain’s most exciting young poets and author of the acclaimed

‘Bee Journal’

By the time Sean Borodale stepped into the middle of a swarm of ‘fizzing thousands’ he had already been stung thrice. Now, though ‘netted in trawls of strumming bee,’ his discarded gloves leaving his arms unprotected, Sean felt in no danger. In fact, the bees barely seemed to know he was there – after months of relentless work, they were lost in the ecstasy of swarming. It was for them, a kind of sacred holiday and Sean, their keeper, was welcome in their midst.

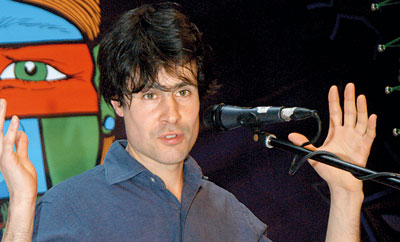

Sean Borodale addressing Colomboscope

The extraordinary experience he captured in the poem titled ‘3rd July: Gift’ comes somewhere toward the end of ‘Bee Journal’, an exquisite collection of poetry that was in the running for the T.S Eliot Prize for Poetry and The Costa Book Awards last year. Sean was also named a Granta New Poet in 2012. The book that has led to his crowning as one of the U.K’s most exciting young poets had its genesis in a working journal, which Sean would write literally at the hive. In those notebooks stained in pollen and honey, ‘bees bathing my pen and poem’s paper’, he attempted to take the crowded present and distil it into a few lines of poetry. (The post editing was extremely light, consisting primarily of the addition of some punctuation.)

The result is a series of poems that read almost like one, 14-month long poem. There are days when the pages are luscious with imagery and thick with summer sounds, others when the words are still, the cold, bleakness of winter captured on a blank page. Sean has said the book is a kind of lyrical seismograph, one where spikes in activity are reflected in poetry. The sound of the hive itself is in these poems. Sean points out that since bees don’t hibernate, the hum is a constant thing. A tap on the side of the hive will rile them up and at one point when wasps attack, he writes ‘distortion in their world is articulate’. On other days, he would simply place his ear, carefully and quietly against the hive to listen to them at work inside.

Sean keeps his bees in a valley behind his home. A river runs close by and winters are cold. Though critics have often seen macro-issues reflected in his poetry – the economy and government surveillance for instance – Sean says his own approach was to be determinedly local. During the time he worked on ‘Bee Journal’ he kept his travelling to the minimum and the poems reflect that intensity of focus.

In his time with them, Sean has found bees to be the most hospitable of all creatures. A quote from ‘Shadow Work’ a book by the Ivan Illich, the Austrian critic, prefaces the collection. ‘Economists understand as much about work, as alchemists about gold.’ The parallels to bees are clear – bees are incredibly industrious and must slave away to produce honey. As Sean writes in ‘Winter Honey’: ‘Much work, one bee, ten thousand flowers a day,/ to produce three teaspoons-worth of this/disconcerting/solid broth/of forest flora full of fox.’ (A connoisseur can tell from the taste what the bees have foraged on.)

Unfortunately, modern bee-keeping methods have resulted in a burgeoning phenomenon known as Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD). Their increasingly dire plight has fuelled several bee protection campaigns, and Sean may read at the Houses of Parliament for the launch of the latest one when he returns home.

In the meantime, Sean (who was in Sri Lanka to participate in Colomboscope at the invitation of the British Council) continues to keep bees, though he has learnt to leave them alone for longer periods of time. His affection for these fascinating insects – ‘part animal, part flower’ – though remains profound, preserved for the record in his gorgeous poetry.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus