Sunday Times 2

When writing works at the pace of walking

View(s):Sean Borodale, who was in Sri Lanka recently for Colomboscope, is a poet and artist; his debut collection was published by Jonathan Cape last year and has gone on to be shortlisted for the T S Eliot and the Costa Book Awards. He was made a Granta New Poet in 2012. He studied at The Slade School of Art and also taught at the Slade. Residencies include those at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, Miro’s studio in Mallorca and at the Wordsworth Trust in the heartland of British Romantic poetry. He has read at the Edinburgh Festival amongst several others and will be reading at the London Festival of Literature and the City of London Festival this year. In October he becomes the Creative Fellow at Trinity College, Cambridge. Sally-Ann Cleaver catches up with him in Galle, and poses some questions.

Explain your working process.

I work as a poet, writing live, often on location, working in the haphazard events of phenomena, and before the language sets into verse; logging the poetic phrase as it occurs. The process of reflection can be a distilling process but often for me fogs the sharpness of the moment’s meaning. Recent works were written whilst walking, or whilst beekeeping, in the pressure of time and concentration, which forces me to risk my instincts.

Describe your recent works.

Recent works include Bee Journal, Notes for an Atlas and Mighty Beast, a documentary poem about a cattle market in the UK.

Notes for an Atlas is a 370-page poem written whilst walking around London; a fifty mile walk along an unprescribed route.

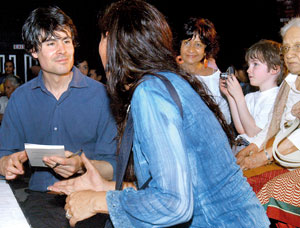

Sean Borodale reading from his book at the recently concluded Colomboscope

I wrote into notebooks as I went, documenting the passing spaces and transient events of the city, step by step. Walking created a kind of metabolic rate or poetic pulse and I was forced to abandon poetic images or phrases, as the next step brought new encounters. I collaborated on a performance of the poem with the actor Mark Rylance who directed it, working with a small cast of four actors.

It was performed at the Royal Festival Hall in London over seven nights in 2007. It never occurred to me whilst writing, but the piece portrays one strand of the possible millions which make up a city, it cuts across the narratives of thousands of life-paths; and it holds a latent act of surveillance, of watching, listening.

Mighty Beast was written at cattle markets in the UK over a year; it then had an airing as extracts of the longer poem at the Bristol Old Vic theatre. It has more recently been developed into a documentary poem for BBC Radio 3, and was first broadcast earlier this year. I went back to interview some of the farmers, livestock handlers, hauliers, who inspired the poem in the first place and the poem itself is in the voice of the auctioneer, full of fast flow and patter and repeating phrase.

Britain has had many set-backs in farming over the past few decades; farming is a marginal life, and I was interested in the market’s physical and metaphoric structure: the central ring, stepped benches, like an ancient classical theatre.

The market days are contractions of the wider landscape, the peripheral communities come into town from isolation. The ritual of the sell is like a procession at the roots of drama, the Dionysian procession, full of its facial expressions, its masks, its stories, and cries; it’s about voice and work on the verge of music.

Can you share something about the poem you have been working on during your stay in Sri Lanka.

I’ve been working on a poem for an anthology, which is really four poems written into and out of each other, about the Casts collection in the Museum of Classical Archaeology in Cambridge, where I held a short residency this year.

Can you give us a few lines from it?

We have to stand dedicating lengths of our time. Amnesia brings new kinds of faith, like instinct, the tooling of damage based on light and theft; there is no other pronouncement, no word, we do not know their sounds; we live no other pageant.

What is your next collection about?

At this point I would prefer not share what my next collection is about, except to say that it’s a sister piece to Bee Journal: it was written in notebooks at the same time as the bee poems and holds a similar approach, and central theme. It’s essentially about change and the alchemy of substance.

What qualifies you to be a poet?

I don’t know if poets are ever qualified.

Continued. from Page 1

Did you work as an artist?

I studied fine art at the Slade School in London; for me it’s not a question of being an artist or a writer; you create, you have to find a language which suits what you mean, or opens your question. But, technically, yes, I worked as an artist. Much of my work was printed or projected into architectural space, and involved text; poetry was a ghost in the middle of it all, though I wasn’t writing poems, I was interested in the making of poetry, and in the forms that a poem could take. Slowly my writing has become my medium.

Describe your work with arts foundations, the projects.

I’ve held a number of residencies: Fellow of the Wordsworth Trust in Cumbria for a year when I was 25, when I followed a route taken by Wordsworth and Coleridge 200 years before me, and wrote what I saw; it was my first walking piece and I printed it on large map-like pages, a novel-length text.

Obliging a member of the audience with an autograph at Colomboscope. Pix by Nilan Maligaspe

Then I was guest artist for 3 months at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, where I typed up Notes for an Atlas, my walk around London. There I lived like a monk, typing from 6 in the morning every day until lunch. After lunch I visited the Rijksmuseum and watched the Rembrandts, and then I walked.

More recently I was writer in residence at the Miro Foundation in Palma, Mallorca; I worked in Miro’s print studio, which was eerie, on a large-scale collaborative artists’ book and installation with the artist Jon Houlding; it involved sound, print, construction of rooms, voice. It was quite a dark piece, in fact, about a conscious entity waking up from severe trauma, in a state of amnesia and disorientation, in an endless labyrinth of dim rooms and repeating objects. The text was meant to be a voice in the head.

Share your experience at Shantiniketan and the artists group We Are International.

When I was at the Slade I set up an artists’ group with a few artists, including Balbir Bodh, who lived and worked here in Sri Lanka with his then wife Druvinka, shortly after that. The group was about finding connections rather than placing boundaries between different cultures and it led to a series of shows hosted by various artists in various places. One such show took me to Shantinikatan and coincidentally, I’d been living at Dartington, which was inspired by Tagore. I remember reading a play of his before I left; I remember one line: ‘the same sun’.

You worked in a foundry?

Soon after We Are International I found myself in a foundry, casting sculptures of artists such as Barry Flannagan, Anish Kapoor, the Chapman Brothers, Tracy Emin, such like. It was only meant to be a temporary job but there was something about it which kept me there, seeing physical images, ideas, finding their way into bronze and other metals, it was somehow alchemic. Many of the works were on a huge scale. I liked the drama, the danger, the 19thcentury hardship of the working day, and the laughs. One of my first jobs was working on a seat by Bill Woodrow, a large open book in bronze, which sits in the British Library today.

What festivals have you been reading at in the past?

Since Bee Journal’s publication, I’ve read at a number of festivals including the Edinburgh Festival, and forthcoming, the London Festival of Literature and City of London Festival.

How was Colomboscope for you?

Colomboscope felt very different from anything else I’ve done. I liked its mix of political, and performing arts, with literature, writing, as a kind of spine. It felt very real, connected, and had a bit of bite about it.

Will Sri Lanka inspire you?

It already has; I’ve made many notes I’d like to work with when I get back to the UK.

What is your best memory of Sri Lanka?

Standing in the middle of a coconut grove and hearing the air move; seeing the ancient frescoes at Dambulla.

Describe your unusual schooling?

I don’t know what makes schooling unusual; however, I had the good fortune to be offered the chance to go to a Krishnamurti school, which I did, in the UK. I also had the chance when I was 17 to visit with all of my school each of the Krishnamurti schools in India. It was an amazing trip and probably changed my sense of the world enormously. I think Krishnamurti’s deconstructing of language, of what we assume to be the case, has been provocative for me as a writer. I still sometimes listen to recordings of his discussions. I think they remind one of the fragility, and the dangers, in language; that language is really a mirage flapping about over something elusive. It is always elusive.

Your wife is an Orange fiction nominee novelist. What are the challenges for a creative literary couple?

Luckily we don’t both write poetry; but our life is chaos, where we don’t keep our minds steady on our work, and really it’s a journey of the mind. We don’t travel much; Sri Lanka is a rare gift. But being in one place, in a concentrated activity, is not a challenge. We often discuss work; home feels like a kind of workshop, a living working space. That feels healthy.

What are your views on Ted Hughes poetry and his private life?

I love the work of Ted Hughes; I grew up with his writing, like many children of my generation. His private life seemed fraught with difficulty, and perhaps with contradiction; but his work is both dark, and sublime. I return to it often.

Can you discuss the balance of work life as a parent.

I did not value time until I had children to look after; it is a wonderful, stressful, parallel journey with one’s own childhood. It adds depth and quality to most perspective, but it’s also tiring. This tiredness brings about a low level delirium. But it’s deeply rewarding, it gives me purpose.

The current Poet Laureate seems to be very supportive of your work.

Yes, she has been very supportive since seeing a small pamphlet I produced (by hand in fact, I stitched every one of the 380 copies I had printed) called Pages from Bee Journal, which preceded Bee Journal. Simon Armitage was also very supportive of that pamphlet; he cited it as one of his Guardian Books of the Year, though it’s hardly a book.

Tell us about your interesting residency at Cambridge.

From October I will be a Fellow Commoner at Trinity College, Cambridge, in the creative arts; it gives time, space and support for two years to my work as a creative writer, as a poet. I look forward to being there very much.

What are your dreams for the future … in art, poetry and life?

That I continue to meet interesting people, places. It has brought me to Sri Lanka; I think that will change me, set new thoughts into the mix. We so often see the roads, but I hope we can leave the roads and learn to walk again. I think walking is key, to our pace, our scale. I hope my writing will work at the pace of walking, that should be its top speed. Above all, to be with my family, to share life quietly.

How has the Eliot changed your life?

Being a T S Eliot nominee has put me on the map, it’s given me a readership, at least for a year. But it’s been a year of surprises; I didn’t expect to be on the shortlist, nor on the Costa Book Awards shortlist. Everything this year has been surprising, including being published by Jonathan Cape. Now I want to get on with my writing.

Describe your intense relationship with nature.

Much of my work is about being very quiet, attentive, speeding the senses up in very slow situations, or trying to steady the senses; to actually move towards their capacity. Nature is just a part of the world. I try not to negotiate in terms of good and bad but to work on a level, to let all things be of interest, as a writer, that is. Nature is a closed word, for me, it’s an easy word. I think as a word it’s almost like junk food. Someone said that form is between the thing and the name. Form is a possibility in the process of effect, a kind of catalyst, not a dead shape. The word nature is a dead shape. Looking at changes, no matter how small, at transformations; I suppose scientists are sometimes better lookers than artists. But it’s about more than looking, the relationship with the forms of the world we are of, it’s about the failure to notice, and the odd weird reflexes which spring up in the gaps. I’m interested in the gaps, the lapses, the out-of-focus. That’s where art, where writing, extends the senses, in the way I’d hoped the bee hive, or the walk, would re-tune the sensory loom. The world is always slightly unrecoverably out-of-focus according to quantum physics; art gives us a possibility, a means to read, and to articulate, to make form. Nature has to be always slightly unrecoverably miraculous.

What are your views on Sri Lanka and nature?

Sri Lanka is a complex, stunning place, it is scarred, for sure, its people are strong, its terrain brimming. I will think about it for years to come.

I have one very strong memory of thousands of butterflies, drifting, in the morning sun around Habarana. It is vital treasure, a vital wet forest, for the entire planet, like the king’s water at Sigirya.

I hope it stays well.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus