News

Views on collision course as Govt. takes U-turn on speed

View(s):Planned highway development to cater to all road users, be it on foot or on wheels, is the key to life on the fast track, experts tell Namini Wijedasa

The main cause of road accidents in Sri Lanka is speed, Transport Minister Nimal Welgama told Parliament in January. And when vehicles crash at high speed, the damage is worse. Developed countries have designated lanes for pedestrians, bicycles and buses, the Minister reasoned. So the likelihood of accidents is low. “But in Sri Lanka,” he said, “space restrictions have prevented roads from being constructed in such a manner. As a result, the risk of accidents is comparatively higher.”

The latest accident on the Southern Highway that claimed the life of one on Thursday. Pic by S. Siriwardena

Four other Ministers and Deputy Ministers emphatically supported his arguments for new motor traffic regulations setting speed limits for all roads under State control. The regulations were presented to Parliament, consequent to a 2008 Supreme Court decision that urged authorities to specify the limits and to erect signposts around the country.

A board comprising officials from several ministries and departments had decided anew on the limits. Road conditions and research by the Road Development Authority (RDA) were duly considered.

The limits are 40 kmph within and outside towns for land vehicles, three-wheelers, three-wheel vans and special purpose vehicles; 50 kmph within towns for motor vehicles, motor coaches and lorries; 60 kmph outside towns for motor coaches and lorries; and 70 kmph outside towns for all other motor vehicles including cars and jeeps.

But on Monday- just 10 weeks after these regulations were passed in Parliament, President Mahinda Rajapaksa said, existing speed limits will be raised. While people routinely thank him for building good roads, he said, they also gripe that they “are catching us at every 100 feet”.

The speed limits date back to the 1940s, and were designed for roads that were eight feet wide, he continued: “So we are going to increase it a little”. This part of his speech, delivered at the opening of the rehabilitated Padeniya-Anuradhapura Road, was widely publicised, while the remarks that preceded it didn’t receive as much coverage.

The President had said that, when a Chief Minister recently visited the Kurunegala Teaching Hospital, an injured man with an arm and leg strung up in casts, beckoned to him with his free hand. He had scolded the Chief Minister soundly, saying, “You all have carpeted the roads, now people are knocking us down. What will you Ministers do about this?”

“There, you have your answer!” laughed Prof. Amal Kumarage, Immediate Past President of the Chartered Institute of Transport and Logistics, when asked what the danger was in revising outdated speed limits. Prof. Kumarage admitted that commuters today want to spend less time on roads. Even with rapid road construction in Sri Lanka, overall speed limit keeps plummeting. He projected that it will continue to decrease, despite the ongoing expressway programme and highways rehabilitation.

But increasing speed limits was only one of many — and often one of the least contributory aspects of reducing travel time, Prof. Kumarage stressed. More effective were reducing congestion, managing intersections, reducing impact of roadside development and realigning curves.

“Improvement of road surface will encourage drivers to go fast,” he explained. “But this may exceed design speed. This is why most improved roads result in a spike in accidents, as only the surface is improved in most instances, leaving curves, roadside developments, junctions as before.”

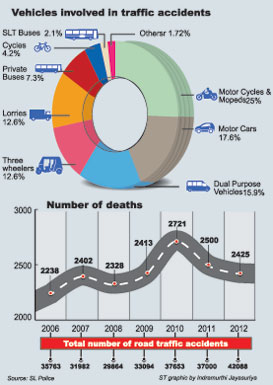

Research showed that little over 60 per cent of serious road accidents in Sri Lanka are speed related. “At higher speeds, the degree of damage is also higher,” Prof. Kumarage said, echoing Minister Welgama. “Thus, a 10 kmph increase in speeds is likely to improve the accident burden by as much as 20 to 25 per cent.”

Although the President did not say it in his speech, informed sources reveal that the revision under consideration is an increase of the 70 kmph limit to 80 kmph. Rohan J. Abeywickrema, a transport and logistics professional, said, raising speed limits was a positive move, provided other requirements were addressed. For instance, it was essential to improve driver discipline. Facilities for pedestrians and cyclists were equally important.

“People develop roads with heavy investments,” he observed. “On either side of the road are drains, and next to the drains are the walls of people living alongside the road. So where do you walk? On the main carriageway used by luxury vehicles and others like small cars, buses, three-wheelers and lorries!”

Economic Development Minister Basil Rajapaksa was recently reported as saying that people started getting run over after a certain village road was improved. When the third person died, villagers blocked the road and demonstrated. “This is the reality at grassroots level,” Mr. Abeywickrema said. “This is what a lot of us don’t understand. For the poor person walking or cycling, road improvements have actually made their lives dangerous.”

“A good road is a myth,” he declared. “A road becomes good when there are facilities for everybody. They are thinking about 3 per cent of the population in cars and forgetting about the 97 per cent.” Dr. Lalithasiri Gunaruwan, a transport professional and lecturer, said, he personally agreed that the speed limits were too restrictive, particularly when roads were better. “Academically speaking, what is the purpose of improved road conditions?” he queried. “To reduce travel time and vehicle maintenance cost. If existing speed limits represent a barrier towards that, I think it’s rational to reconsider speed limits.”

Having said that, Dr. Gunaruwan added, there were other parameters to look at. Required road conditions- such as curves with proper cants to prevent skidding, must be met. He also said effective road usage regulations must be introduced. And there must be pavements and cycle lanes. “Because, more than the value of time saved is the value of lives saved,” he asserted.

There were sections of road in Sri Lanka where the speed limit could be increased under certain conditions, Prof. Kumarage said. “However, a general increase, especially at a time when compliance to speed limits and enforcement is extremely lax, would have grave consequences,” he warned.

So what else did the President say? He grumbled that people were now scolding his Government for having carpeted the roads. People will drive faster even on the road he had just inaugurated, he said. But if cyclists kept to their designated lanes (for this road did have such lanes), there will be fewer accidents.

But there will be other issues once the speed limit is increased, the President admitted. “It will be a problem for pedestrians,” he nodded. “That’s why we have issued instructions that all roads being constructed from now on must have pavements.”

Well and good, accept the experts. But what of the rest?

Modern vehicles geared for speed on well paved roads

Several years ago, two foreign journalists — a Canadian and a Spaniard — were being driven around Sri Lanka on assignment. After three days of rattling over rutted, uneven surfaces, they happened upon a stretch of road which was blissfully smooth and empty.

This was the Habarana-Kantale road. On either side were teak plantations and quaint village dwellings with big gardens and mango trees. There were no curves or traffic, so the driver had an unhindered view. The asphalt surface was even. The elephant crossing signs were further ahead.

The driver pressed the accelerator. He didn’t get far. Two traffic cops had been lurking, as they are wont to do, behind a tree. One wielded a speed gun. The driver’s licence was confiscated.

The journalists were astounded. “What!” exclaimed the Spaniard, “You finally come to a road which is so good that you can go fast and they catch you. There’s no traffic, nobody around!”

It’s a common reaction. Even on good, uncongested roads, drivers are mandated to stick to the 70 kmph speed limit. But as our story shows, many seen and unseen factors must be considered when deciding on speed limits.

The Sunday Times asked vehicle users if they thought speed limits should increase. The question elicited some amusing responses.

Here are excerpts:

- “The present speed limits are way too slow, especially outside Colombo. This has allowed cops to use it as a tool to make a buck. In certain places outside the city, such as the Puttalam Road which is a good example, 80 kmph or even 90 kmph is a very safe speed. But the limit is only 70 kmph, which is painfully slow! Naturally, people speed up a little and end up having to pay fines. This also makes driving stressful, because you’re always expecting a cop to jump out of the bushes waving a speed gun!”

- The roads are very good compared with what they were. But, say you are now legally hammering down a road at 80 kmph. Does it stop the three-wheeler driver changing his mind and, therefore, direction and doing a U-turn across you? I think we need to first learn the rules, which I know many cops don’t know, and then abide by them, before we find new depths for our right foot to reach.”

- “In all honesty, nobody sticks to the speed limit, at least in Colombo. I don’t think it will make a difference in the city. People are always driving at the maximum speed possible. Outside Colombo, I think the increase will help. Roads seem pretty good now. I went to Trincomalee recently, and the road was awesome all the way, except the last bit which is still under construction. But the speed limit was 70 kmph, agonisingly slow. Speeding fine was Rs. 500. So I kept Rs. 2,000 in Rs. 500 notes, and drove around at 100-110 kmph! Even if I got stopped, I would have paid the spot-fine of Rs. 500, and just continued speeding, because it’s a long drive and doing it at 70 kmph is horrible.”

- “I’m in favour of increasing the limit, because nobody can really be expected to drive at 70 kmph. Vehicles like buses and trucks that speed and cause accidents anyway don’t adhere to the posted limits. So keeping the limits low, probably, doesn’t reduce accidents in the way one might think it would. Plus, I’ve heard that most cops don’t stop buses on certain routes, whether or not they break the laws, because the buses are owned either by politicians or their henchmen. And we all know what would happen to a cop who dares enforce the law against those that are above it.”

- “New cars can reach 50 kmph in a couple of seconds. Most of them are automatic and they pick up as we drive. So it’s a real nuisance to go outstation, because you’re constantly hitting your foot on the pedal and trying to control the speed. You waste time and fuel and kill your engine.”

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus