Doing the Grand

View(s):A classy coffee-table book invites the reader to discover – or rediscover – Nuwara Eliya and its most famous hotel. Stephen Prins takes a look

Going up to the hill country resort of Nuwara Eliya has always been a rather grand proposition. Grand in the sense that Nuwara Eliya has cachet. Everything you have heard about the place has an aspect of grandness about it. The words carry prestige. You can impress people when you say you are Nuwara Eliya-bound. But not everyone is a Nuwara Eliya person. Some swear by it as the country’s ultimate holiday destination and love it for its “Little England” qualities, while others prefer to keep Nuwara Eliya at a distance – for their own reasons, some being that the resort is a tad too elite, too expensive, or too far.

In our case, Nuwara Eliya has always been that out-of-the-way place, outside Kandy limits. When we were children, all our holidays in the hills were centred on Katugastota, in an old sprawling house with a tiered garden overlooking the Mahaweli Ganga. Everything a family or a child needed for a “complete” vacation was to be found within the wondrous Walbeoff estate known as “The Park.” We had no need to go further. Nuwara Eliya could wait.

As a result, we can count the number of our visits to Nuwara Eliya on the be-ringed fingers of one hand. Two? Three? We don’t exactly remember. And these few visits were really whistle-stop calls, not stays. We were passing through, years ago, and have therefore only the haziest memories of the resort.

Flower-fringed pathways and a garden just as grand

Our most recent visit, in mid-March, just before the Nuwara Eliya season’s official opening day, April 1, was prompted by a a very classy book that was placed in our hands for review – “Grand Hotel Nuwara Eliya.”

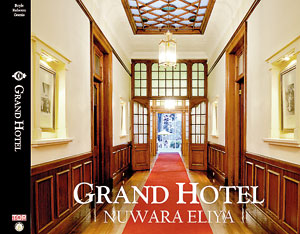

The coffee-table book is sumptuously illustrated, with historical and contemporary photographs and assorted artwork. The bulk of the photographs are by Waruna Gomis, with additional images by Kesara Ratnavibushana. The lovingly researched text is written by Richard Boyle, who was assisted in the fact-finding by Ismeth Raheem, architect, archivist, artist and art collector. The making of the book has been put in the best of hands. Boyle is an Englishman who has made this country his permanent home, and he and Raheem are passionate Sri Lankophiles, with a historian’s deep love and respect for things Ceylonese or Sri Lankan. The book is published by Top Property Group and L&A Publishing, and the handsome print job was handled by Gunaratna Offset. The result is a book to hold and behold, one that has all the information anyone might require about the hotel and Nuwara Eliya, and a lot more, all offered in a generously informative and sharing spirit.

Tucked in its smart black hardboard slipcase, one compactly folded within the other, the book and its container suggested the neat way the posh colonial-era hotel is tucked in the fancy hill station. For the story of the Grand Hotel is also the story of Nuwara Eliya.

The hotel in its original form as an Englishman’s private home is almost as old as the salubrious valley “discovered” in 1819 by Dr. John Davy, physician to Governor Sir Robert Brownrigg, although it was another Englishman, Robert Knox, who first put “Newer ellea” on the map, literally, and that was much earlier, in 1681, in his famous chronicle of old Ceylon.

Credit for taking the actions, road building among them, that led to the creation of Nuwara Eliya as an enclave for the British community goes to British Governor, Sir Edward Barnes. A band of soldiers who had stumbled into the valley while chasing an elephant reported their discovery to Governor Barnes, who came up to inspect the location and liked it enough to build there a military hospital, a kachcheri, a jail, and a house for himself on 38 acres of land that he purchased. Over the next 100 plus years, Barnes House would undergo structural alterations and expansions and changes in ownership that would result in the present Grand Hotel.

The book’s first five chapters are about the growth of the hotel, the many evolutionary stages it underwent before it assumed its present form. The rest of the book is about what the hotel offers in comfort, accommodation, food, drink and entertainment.

The recent afternoon we arrived in Nuwara Eliya was overcast and drizzly. Tourists and locals strolled around in raincoats and jackets and carried umbrellas. As we made our way up the Grand Hotel’s sweeping driveway, we observed much activity in the garden. Gardeners were busy trimming bushes and trees, and flower beds were covered in sheets of plastic. “To protect them from frost,” explained an authoritative gentleman standing in the driveway who introduced himself as Sathasivam Sathasakthianathan, the garden and farm manager. “Come in the first week of April and see the roses and other flowers in full bloom,” he called out as we entered the hotel. At the concierge desk, deep inside the hotel, we explained that we were here to see for ourselves the “grand reality” of the place we had been reading about. A display copy of the coffee-table book was propped up on the front office desk. Mr. M. B. Rafaideen, front office executive, offered to take us on a guided tour of the hotel and the garden.

The tour included all public areas on the ground floor, including the Red Lounge, the Piano Lounge, the Tea Lounge, the Tea Veranda, the Grand Ballroom, the Magnolia Coffee Shop, the Wine Bar and the Billiards Room. We also visited one of the luxury suites. Old and new. Space and style. Lots of period furniture.

In a part of the sprawling, spotless, multi-level kitchen complex, executive chef Arosha Jayasinghe demonstrated a dough mixer that was more than a century old and worked perfectly.

We then descended several flights of steps into the cavernous basement, which contained the laundry rooms. We were shown a 19th-century pressing machine that worked perfectly and was more reliable than its 21st century high-tech equal. “When the new machine breaks down, we turn to the old contraption, which has never let us down,” said Mr. Rafaideen. To demonstrate the power of old over new, the staff pressed pieces of freshly washed table linen which emerged crisp, sharp-edged and ready for a banquet table.

Back on ground level, we asked to be shown around the garden. “This is the only hotel in the country that has a continuous garden that runs right around the hotel,” Mr. Rafaideen said as we made our way along a path that ran past flower beds, strips of lawn and stretches of gravel.

“It’s time for tea, you must join us,” called out hotel resident manager Tyrone David as we re-entered the hotel. A rushed Mr. David excused himself as he was overseeing a busload of new arrivals.

Tea was served in a spacious room overlooking the front lawn. “This was formerly an office room – it was recently converted into the Dilmah Tea Lounge,” said front office manager R. Muthuramesh, who had just joined us. The two front office gentlemen took turns talking about the hotel.

“This is a heritage property and we follow a policy of continuous improvement,” said Mr. Muthuramesh. “All improvements or new features must be in harmony with the old. Our guests include foreigners and locals. We have a lot of American, British, Indian and Japanese guests. Our staff headcount is 330.”

Spacious: A room in the superior category

We gazed out into the garden where, between spells of rain, the gardeners worked on. The atmosphere inside and out was one of high expectation. Everyone was busily working towards the big day, April 1, when Nuwara Eliya regulars and others would flood the town. Even the flowers bloom on cue on April 1, said a smiling Mr. Rafaideen.

Our next visit to Nuwara Eliya would have to be very soon if we are to enjoy the town in full bloom. So this is famous Little England in the Hills, we told ourselves, sipping tea and remembering that it was the British who brought tea, among other things, to this country.

It so happens that we grew up next to another Little England, in Colombo, so we did know something about the ways and habits of the remaining British as they quietly live their lives in post-colonial Ceylon. This Little England was situated next door and comprised two near identical properties – upstairs homes set in the middle of beautifully kept gardens and lawns. Our own home and garden, Weimar, was separated from this Little England by a side lane that branched off a by-lane that in turn branched off a dignified, rather royal, road near the University of Colombo campus.

One English house hid exactly behind the other. More like manor houses, the properties belonged to a prominent English firm that had set up in Ceylon at the turn of the 20th century. The occupants were English and Scottish.

Both houses and gardens belonged to another country, where even the trees and bushes were different. There seemed to be a lot more light here than in your average Colombo garden, with its ponderous trees and dark heavy foliage. Along with Younger Brother, we spent hours in trees inside our garden spying on the quiet world of Little England. During the day, when the Englishmen and Scotsmen were away at the office, we would talk to Joseph the Gardener and with his permission slip into the first garden, the one visible from our “rata goraka” and jambu trees. We were in another land. The plants and flowers were different, unfamiliar, and the perfect lawn was bigger than a football field. We wandered around, as Joseph cut the grass with a battery-powered lawnmower, and a sprinkler spun silvery rain in a far corner.

With the permission of Tommy the Butler, we would enter the first house and look around in wonder. Everything spotless, everything in place – chairs and tables on side veranda, and in sitting room and dining hall mirrors, flowers in crystal vases, and impressive furniture with gleaming brass fittings. All was unfamiliar in a familiar way. The smells were different too. Strongest was the scent of order, squeaky cleanliness, and quality. So this was England. It smelled wholesome and good.

We don’t remember how often we sneaked into Little England, but as it was right next door we must have gone there umpteen times – until we were old enough to know the time was past when we could get away with trespassing on other people’s property, entering another land without passport and visa.

It is now almost May and we should be preparing to make that five-hour journey into the hills again, spurred on by the enthusiasm that breathes in the pages of Mr. Boyle and Mr. Raheem’s excellent book.

One suggestion to the publishers: At Rs. 8,500, the coffee-table book “Grand Hotel Nuwara Eliya” is well out of the reach of most of us book lovers. For general educational purposes, why not publish the text separately in an affordable edition and with sufficient illustrations to make it a worthwhile buy? The text is too good, too rich in historical information about the hill country and the country in general, and too full of fascinating anecdotes to limit it to an expensive conversation piece that, as with most coffee-table books, end up being more looked at than read. Make the book accessible to a wider public.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus