Modern technology an own-goal for some sports

View(s):Would Muttiah Muralitharan have taken more than 800 wickets if the DRS had been introduced to cricket earlier? The answer is yes. So is technology good for cricket? Again, the answer is yes. So does this mean all sport should rely on machines? Definitely no!

More on Murali later, but let’s first take a look at the latest sport where the warm human element will be overshadowed by cold machinery – football.

Call me a dinosaur, but goal-line technology to be introduced at next year’s World Cup by Fifa will rob the beautiful game of its soul, its very essence.

After years of heated debate, goal-line technology will be implemented into the soccer world next season. It won’t come cheap.

Fifa has chosen a system for use at the Brazil World Cup that will rely on 14 high-speed cameras set up at both goals. England’s Premier League will use the British-invented Hawk Eye.

Michel Platini, the president of UEFA and a long-time opponent of goal-line technology has revealed that it will cost US$71 million to equip the 280 stadiums used for Europe’s top club competitions with this modern gadgetry which can deduce if the ball has crossed the line or not.

It robs the romanticism from the game. The most famous controversy surrounding whether the ball crossed the line or not occurred in the 1966 World Cup final between England and Germany. England won 4-2 with Geoff Hurst scoring a hat-trick which included a goal which bounced down of the underside of the crossbar.

The referee was uncertain and had to rely on the linesman who said it had crossed the line to give England a 3-2 lead. Hurst wrapped up victory with his third goal in the closing seconds.

His second goal became a talking point for soccer fans over the years. The controversial call by the Russian linesman has been debated in bars all around the world whenever football fans get together, especially from England and Germany.

Hurst, later, in 2011, admitted that the linesman got it wrong and his second goal shouldn’t have been awarded. Seen in this light, you may think that a miscarriage of justice had occurred. But yet, Hurst scored his third goal to make the final score 4-2, s there was no sporting injustice.

What goes around comes around. Life has a funny way of constantly reminding us of this. At the 2010 World Cup, the boot was on the other foot. I remember watching the game between Germany and England with some old school friends at the Hilton poolside in Colombo.

Frank Lampard hit a scorcher which like Hurst’s effort 44 years ago, hit the under-bar, but this time was seen to clearly cross the line. Everyone watching it on TV saw it, except for the people who mattered – the referee and linesman, and the goal was not awarded.

England was trailing 2-1 at that time. A superior Germany outfit went on to win 4-1. Once again there was debate. If Lampard’s goal had stood, would it have renewed confidence among the English and sparked a comeback?

But once again the overall sense of feeling was that the better side had won. Germany was worthy winners so no injustice was done as in 1966.

Which raises the issue is goal-line technology really needed in football. Incidents like the two above occur very rarely. On most occasions, when it does happen, the referee and his linesmen get it right. But unlike in cricket, such occurrences are very rare indeed so taking away the human element is a shame.

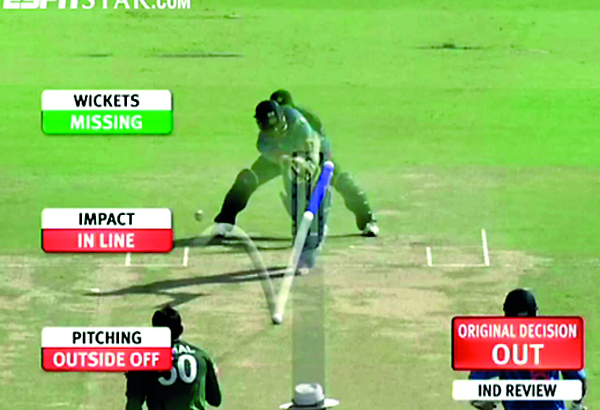

It is a different story in cricket because a shout for a LBW is never far away from the bowler’s lip. The ball hits the pad often. The umpires who stand have a number of things to do, watch for the no-ball and then quickly have to size-up if the ball is going on to hit the wicket, whether there was an inside edge, or if the ball was outside the line of the wicket.

So many decisions to make in a split second, and unlike in football, this goes on for hours and as such human error can creep in. The DRS, or decision review system, offer officials the chance to rely on outside help so that they can make a correct decision.

A recent study showed that Muralitharan, Shane Warne and Anil Kumble who took 800, 708 and 619 wickets respectively would in a parallel universe – one in which the DRS had existed from the beginning – ended up with 851, 755 and 670 wickets each.These figures are based on a DRS weighting, which takes into account the percentage of Lbws in 2012, each bowler’s percentage of Lbws and the overall percentage of Lbws during the exact time-span of their Test career.

In the end, each sport must decide what is best for their code. But the blanket use of technology is a shame for you cannot compare apples and oranges.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus