News

West Nile Virus making people ill here

Joint university study identifies it as causing brain fever

A virus causing brain fever, a culprit in epidemics in some countries across the globe, has been identified for the first time in Sri Lanka as causing human disease here, by an important Colombo-Sri Jayeawardhanapura University joint study.

The West Nile Virus (WNV) was identified as the cause of brain fever (meningoencephalitis) in two people admitted to the National Hospital of Sri Lanka (NHSL) in November last year, the joint research by the Medical Faculties of the Universities of Colombo and Sri Jayawardhanapura has revealed.

A stretch of dirty water in a canal at Maligawatte could be a potential threat to spread the virus

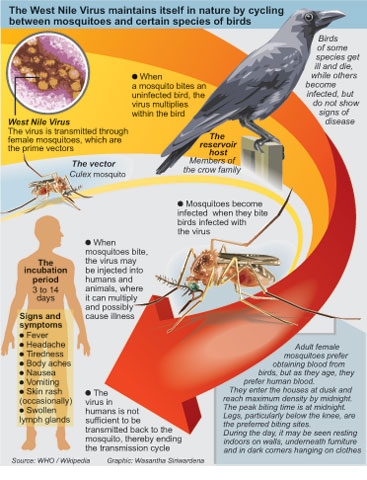

While the virus is transmitted by the Culex mosquitoes (those also causing filaria), ‘perching’ birds commonly found everywhere such as crows, magpies, house sparrows, mynahs etc., act as the “amplifying reservoir hosts”, the Sunday Times understands.

This means that when the virus gets into birds through the bites of infected mosquitoes, the virus multiplies in them. Thereafter, when mosquitoes, in turn, bite these birds which are carrying sufficient levels of the virus and later bite humans, WNV is transmitted to humans.

The identification of the virus as causing disease in humans in Sri Lanka brings to the fore a major public health concern and the need for immediate action to curtail the breeding of the Culex mosquitoes by cleaning up polluted waterways and water collections.

The need of the hour is to prevent WNV from reaching epidemic proportions, cautioned the joint research team.

The research team comprised Specialist Neurologist Dr. Thashi Chang of the Department of Clinical Medicine and Specialist in Community Medicine Dr. Carukshi Arambepola of the Department of Community Medicine of the University of Colombo; Consultant Immunologist Dr. Neelika Malavige of the Department of Microbiology, University of Sri Jayawardhanapura; and post-graduate research student Janarthani Lohitharajah. They were supported by the Neurologists and Physicians of the NHSL and the Lady Ridgeway Hospital (LRH) for Children, Colombo, while the study was funded by the National Research Council.

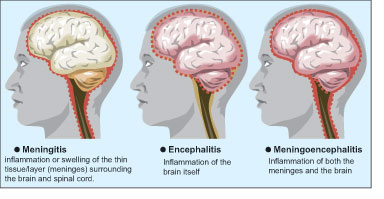

‘Brain fever’ describes three conditions caused by infection which leads to the inflammation (swelling) of the brain or its protective coverings (meninges). Infection of the protective coverings causes ‘meningitis’, while infection of the brain itself causes encephalitis. A mix of both causes meningoencephalitis.

Meningitis is commonly due to bacterial infections while encephalitis is commonly due to viral infections, it is learnt.

While meningitis is treated with antibiotics, encephalitis which could be caused by one of many viruses has only aciclovir as a medication. But aciclovir acts only against the Herpes simplex and Varicella zoster viruses, points out Dr. Chang.

The next important question was whether Herpes simplex and Varicella zoster are common in Sri Lanka. If not, what were the viruses causing brain fever here? Although the main culprit in Sri Lanka seemed to be Japanese Encephalitis (JE) if Asian patterns were taken into account — for it made 35,000-50,000 people ill and brought death to 15,000 people every year — were there other viruses?

There was a “huge hiatus”, says Dr. Chang. With brain fever having a poor prognosis as some patients died and even those who recovered losing their intellectual functions in the long-term, the interest of the researchers was aroused to identify other viruses causing this illness.

We began looking at samples from patients at the National Hospital and the LRH, said Dr. Malavige, with the research beginning in earnest in November 2012.

They studied over 40 patients, according to Dr. Chang, collecting clinical data and requesting the NHSL and LRH Neurologists and Physicians — who as part of the tests before patient management carried out spinal taps — to give them a small quantity of the spinal fluid.

With WNV being present in neighbouring India including Tamil Nadu, just across the Palk Strait, their tests for it in two patients at the NHSL paid off, explains Dr. Malavige, pointing out that it could have been brought into Sri Lanka by migratory birds coming here from other countries to avoid the winter. Then the local birds could easily become reservoirs after Culex mosquitoes bite the infected migratory birds and then bite them.

Thereafter, it would be only a matter of time for the Culex mosquitoes to transmit it to humans, the Sunday Times understands.

Although person-to-person transmission does not generally occur, according to the researchers, in other countries some infections have resulted from the transfusion of blood products and organ transplantation.

It is very difficult to differentiate whether it is WNV, JE or Dengue, even through antibody tests, Dr. Malavige said. But once they came up with the result that the brain fever in the two NHSL patients was due to WNV, the samples were sent for confirmatory tests (the Plaque Reduction Neutralisation Assay) to the accredited reference laboratory of the National University of Singapore (NUS).

The ‘history’ of WNV in the world begins in 1937, when it was first isolated from the blood of a feverish Ugandan woman, according to the researchers. Subsequently, the virus was detected throughout Africa, Asia and Europe.

It was considered a major risk to humans only after outbreaks of encephalitis in Algeria in 1994 and Romania in 1996. Since its first detection in the US in 1999, it has now emerged as the most common cause of epidemic encephalitis in North America accounting for almost 20,000 cases and over 780 deaths from 1999 to 2005 in the US, it is understood.

Although antibodies against WNV have previously been reported in cattle and goats in Sri Lanka, there have been no records of human disease, the researchers add.

Majority of persons affected do not show any symptoms

Many people who may be infected with WNV do not show any symptoms. Eighty percent of those infected with the virus are asymptomatic or do not manifest any symptoms, say the researchers, pointing out that only 20% will have flu-like symptoms which are self-limiting or run their course.

However, 1% will develop serious neuro-invasive diseases in the form of meningitis, encephalitis or acute flaccid paralysis (sudden weakness or floppiness in any part of the body). It could be fatal for some while for others the recovery would be long, leaving them with disabilities, the Sunday Times learns.

There is no specific treatment and no vaccine against WNV. The patient’s body has to fight the virus and get rid of it, says, Dr. Chang, adding that hospitals would provide supportive therapy including maintenance of nutrition, hydration, fever-management and treatment of complications.

Older people, those above 50, and those whose immunity is low are more vulnerable to WNV, research in the United States has found.

Mosquito control is best strategy

Prevention is definitely better than the cure, should be the obvious strategy with regard to WNV. With evidence on the table now that WNV is a cause of human disease in Sri Lanka, mosquito control remains the most effective preventive strategy, the researchers stressed, cautioning that the current focus on dengue mosquito control perhaps has resulted in inadequate measures to eradicate Culex mosquitoes.

Alerting the authorities to take urgent action to prevent WNV from reaching epidemic proportions, they also pointed out the need for awareness and knowledge with regard to the symptoms not only among the people but also doctors. “This would ensure timely medical care which could reduce the complications of neuro-invasive disease.”

While surveillance for WNV around the country would help curb the disease, measures to find out the number of birds affected by it would give an indication of the extent of the problem, they say, adding that if there are any reports of sudden bird-deaths veterinarians and doctors should work in tandem to investigate the causes.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus