Building on happiness

The first female architect to deliver the annual Geoffrey Bawa Memorial Lecture Kate Otten discusses her ground-breaking work in post-apartheid South Africa

Over the course of 23 years in architecture, Kate Otten has come to believe firmly in the need for “happy” buildings. The one she’s staying in right now seems to qualify this. It’s the house Geoffrey Bawa built off Bagatalle Road and the Number 11 guest suite is home to her and a friend for the next few days. “It’s not huge, big architecture with a capital ‘A’ but it’s about how people experience it. The architecture doesn’t dominate. The use of the space dominates and how people feel in that. It’s around people, and how they live…there’s a subtlety that’s just beautiful,” she says.

In the days to come Kate will be visiting the gardens at Lunuganga and Kandalama but not before she finishes delivering the annual Geoffrey Bawa Memorial Lecture, becoming the first female architect to have done so.

She met Bawa in 1997 when he and Indian architect Charles Correa arrived in South Africa to judge the competition for the New Constitution court. Kate remembers the competition as a vital step toward breaking the dominance of white Afrikaner men who were the usual beneficiaries of government projects. “There was no such thing as proper competition. This was the first competition that was open to everyone instead of just to the Afrikaner cabal.”

Kate would get to work on the section of Constitution Hill known as the ‘Women’s Jail’ – a former prison famed for its brutality that was now being converted into the new home for the Commission for Gender Equality. Some of the people who would occupy the offices were once inmates of the three prisons that were being converted into a living museum and exhibition spaces and Kate found herself challenged by the need to simultaneously preserve and transform. As part of the solution, Kate and her team would build a few new structures and retain some of what they found – such as the old Awaiting Trial building as well as the space that used to be the exercise yard. Determined not to beautify it overly, Kate chose to impart a certain symbolism to her work in her choice of materials and layout. She also worked on the restoration of Jo’burg Fort in Constitution Hill.

The project went a long way toward making Kate one of South Africa’s most prominent architects. Having set up shop in 1989, she already stood out with her unconventional staffing choices. “My office is exclusively women and it always has been,” she says explaining that it was a conscious decision. Since her mother was a doctor, she never questioned that she would become a professional in her own right. However, she’s remained keenly conscious of the challenges her gender faced in the field. As a result she says she has consciously nurtured women in architecture, especially women from disadvantaged backgrounds. She’s proud that women who she once trained now have their own practices and are collaborators. “That’s been a valuable part of the work for me, the question of who is doing it.”

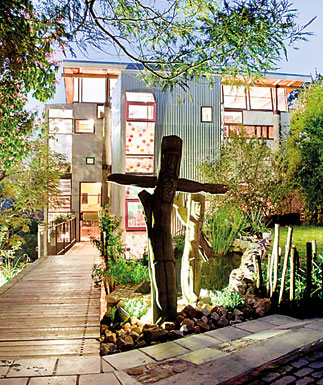

Lulu Kati Kati: Kate Otten’s ‘suspended’ design and (top) Kate Otten in Colombo

The question extends into the very fabrics and techniques she uses in her buildings. ‘Philosophically, our work is mindful of place and people – we work within the African tradition of spaces being emotional carriers of meaning. Our buildings are ‘happy buildings’; fabricated landscapes where light, colour, materials, texture, and the change of seasons all interplay to delight the senses and lift the spirit,’ she writes. This has meant working with, and reinventing the image of humble materials like brick and corrugated iron, both of which feature prominently in her designs. Labour is made up of local craftspeople thereby allowing local skills, locally available materials and local conditions to dictate their designs.

In her Geoffrey Bawa lecture that night titled ‘Landscapes of the Spirit’ Kate chose to talk about “making places that uplift the spirit and shift the perceptions even as they fulfil their function.” Among them were the art therapy building she designed in Soweto, (the location of a tragic uprising in 1976), the International House (a residential block for students) as well as private homes like the Pringle Bay House, the House Altman-Massdorp and Gabriel’s Garden Pavillion, for which she created home office spaces within the historic gardens of a national monument. The projects closest to her heart though, may very well have been the homes she designed for herself and her small family.

House Pitsillides – for which she and her husband agreed that she would be the architect, he the customer – an airy 60s style ranch building offers a lovely contrast to the much more intimate Lulu Kati Kati, completed just in time for the 2010 Football World Cup. Lulu Kati Kati meaning ‘pearl in the middle’ was built on a left over sliver of land at the end of the high street in Melville, Johannesburg. Nestled in between a natural rock face and an 80-year-old Dombeya tree, the building is suspended – quite literally – from 6 massive gum poles, each 9.5m tall and weighing in at over half a ton. “To live here,” she said, “is to feel alive.”

Looking back on her career in architecture, Kate sums it up neatly: “Ultimately, my journey has been one of navigating the times into which I was born, and using architecture to make a line in the sand, a quiet act of rebellion and refusal to acquiesce to a crushing of the spirit.”

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus