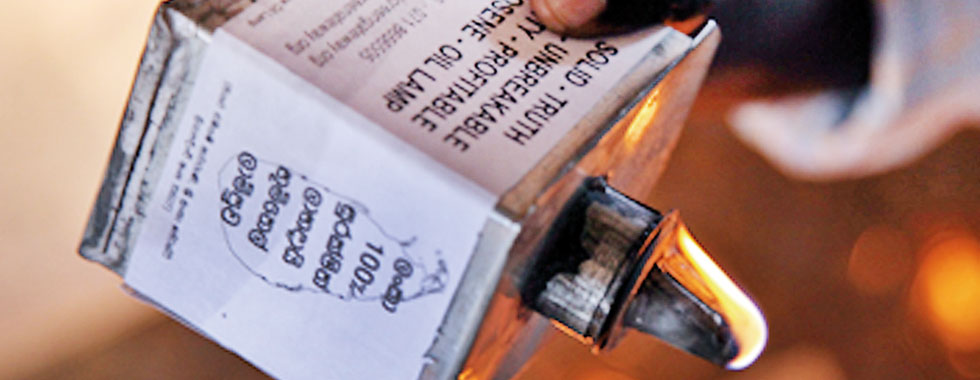

Not Aladdin’s magic lamp but Jayawardana’s

More than 30 years after it was invented, the ‘Lanka Lamp’ is finally ready to reach households all over the country

It took Lanka Jayawardana over three decades to patent and make public his groundbreaking innovation; the Lanka Lamp was invented in 1980. Mr. Jayawardana, a former civil servant, found that the biggest hurdle in developing this lamp was not the creation itself but rather getting it out there to the public. “I gave up after a while,” he sighs. “It was very disheartening.” However when Dr. Wijaya Godakumbura came out with his Sudeepa safe bottle lamp Mr. Jayawardana was encouraged by the reception it got and restarted campaigning for his invention. In 2012 he finally obtained the patent rights for the ‘Lanka Lamp’.

Lanka Jayawardana

The 74-year-old inventor is confident that his lamp will be a boon to households across the island relying on oil-based lamps for illumination. This confidence is certainly not unfounded-since making the device public he has won a National Excellencey Award and has been shortlisted for a host of awards and accolades including a Presidential Award for Innovation.

Lanka Jayawardana hails from the town of Dalupathgama, Kurunegala. He obtained a scholarship to Anuradhapura Central College for secondary education and studied in the Science stream for his Advanced Levels. A short stint at a farm school before moving to the University of Peradeniya for his higher studies had Mr. Jayawardana hooked on agriculture science.

Following his graduation he worked at the Kantale Sugar Corporation, swiftly moving onto a series of state institutions as an employee of the Department of Agriculture. It was an exciting and constantly changing lifestyle that he found great joy in. “I’ve worked in all nine provinces you know,” he says with a touch of pride. “That’s the interesting thing about working in the public sector.” Transfers galore, he adds wryly.

Known as the ‘iron man’ of his profession at the time, Mr. Jayawardana was responsible for the strengthening of B-Onion cultivation in Sri Lanka in 1967 and went on to drive several advancements in the agricultural industry, eventually being thanked in writing by President J.R. Jayewardene. He shows us an ageing copy of the letter which he keeps in a file full of such documents. In the 70’s he met and married the light of his life, wife Thalatha. Together, they travelled the country as he was transferred several times.

Safe all the way: The small concave shaped guard that envelops the flame should the lamp tilt over. Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kuymara

It was during these travels that he came to realize many families in the country depended on kerosene oil-powered lamps to get them through the darkness of the night. Children studied and parents attended to household matters with the light provided by these lamps. “In Colombo, even at the time, many households had electricity. But in the outstations it was a different matter altogether. Even today many households in these areas are powered by a kerosene lamp.” It’s a highly risky form of illumination, he says. “When I was stationed in Matale five children died due to accidents caused by these lamps. I decided something must be done.”

Mr. Jayawardana who was fondly called a ‘child of the darkness’ by his father (he was born at midnight) set to work identifying the problems associated with the use of the conventional kerosene lamp. Many accidents were caused by the lamp tipping over-the glass beaker would shatter, the oil would spread over a large area and the flame would feed on the spilt oil rapidly engulfing the room in flames. “The major problem was with the liquid nature of the oil,” he says. “It cannot be contained.” The obvious solution then, he felt, was to solidify the fuel.

This was easier said than done however. He spent a considerable amount of time trying over a hundred different materials to figure out the solution. Eventually, he chose a most ingenious method of using wood shavings to soak up the oil. By letting them soak up the dangerous kerosene, the liquid was transferred into a solid form.

Lanka Lamp: Providing an economical use of kerosene oil

Thus the Lanka Lamp doesn’t function without oil in the complete sense, but it does provide a most economical use for kerosene oil. A small box-like contraption (pictured) holds the shavings. The kerosene is poured in through a small opening at the top and the opening is blocked by a small screw. The container must be left for a few hours for the shavings to absorb the oil. Then the excess is poured out (for later use) and the lamp can be lit by setting a match to the wick-this will illuminate your surroundings for about two to three days, says Jayawardana.

What makes the Lanka Lamp ‘100% safe’ is the small concave shaped guard that envelops the flame should the lamp tilt over. “Furthermore, dropping the lamp will not cause any harm as the container will not break,” reveals its inventor.

The lamp is also 70% profitable, we’re told, as the wood shavings only need to absorb a relatively smaller percentage of the kerosene oil than a conventional lamp would have.

With the generous funding and support of several humanitarian organizations he plans to distribute the Lanka Lamp free of charge to needy households across the country. One day he might even take it international.

After all, this is the lamp he fondly likens to Aladdin’s magic lamp. He may not have the universal power of the genie, but his one wish would be to “ward off all evil with the Lanka Lamp!”

Individuals and organizations interested in donating to the production and free distribution of the Lanka Lamp to needy households can contact its inventor on globalgreengateway@yahoo.com

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus