News

CPC’s hedging blunder Finally the people pay

The room was packed; the mood fraught. It was November 2008 and the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation’s (CPC) hedging deals were fast going awry.

Ashantha De Mel, then Chairman of the CPC,

Ashantha De Mel, then Chairman of the CPC, sat at the head table. On his right were the Chief Executive Officers of three of the banks – Standard Chartered (SCB), Citibank and Commercial Bank – with whom he had signed hedging contracts. A news conference was about to begin.

The CPC was confronted with making massive payouts to five local and foreign banks. The reason was simple: Because of the way they had been structured, the hedging agreements did not protect the CPC if world oil prices slid down. They would only serve the Corporation as long as the prices go up.

In contrast, if prices fell below a specified figure, the CPC would have to pay the banks the difference between that and the market price — with no limit on the downside. And while the oil price had peaked at US$ 147 per barrel in July 2008, it had fallen to below US$ 60 per barrel around the time of the news conference. It would drop even further in subsequent months, crashing to as low as US$ 30.

Mr. De Mel conducted an impassioned justification of the disastrous hedging deals. He was upbeat, claiming that they would simply restructure the agreements to mitigate the losses. (This didn’t transpire in some of the contracts because of a detail in the formula adopted).

He also shielded the banks from criticism of “misselling”. “Since starting our hedging programme,” he explained, “the different banks have explained to the CPC the various downside risks associated with each product and we entered into these deals with full knowledge of these risks.”

A media statement was passed around. Among other things, it declared confidently that, even though the CPC had to pay a marginally higher price, the country as a whole benefited from lower world prices.

“The CPC is committed to make the payments as and when they fall due,” it asserted. “There is no question of defaulting on these payments. A default by the CPC will be as good as a sovereign default, which could have serious consequences to the country and its growth prospects. Our cash flow remains strong to meet the payments.”

There is less bravado at the Corporation today. Its cash flow is floundering. And payouts on the hedging deals have added to a massive debt burden which consumers will eventually have to pay. Without having anything to do with the Government’s decision to hedge for oil, or the expensive mistakes the CPC had made in the process, the ordinary public is saddled with the bill.

The CPC’s debt has increased by 52.62% in the three years since 2011. According to the Finance Ministry’s Mid-Year Fiscal Position Report released earlier this month, its outstanding debt stands at more than Rs. 225 billion — “an eye-watering amount,” as one economist defined it.

The Government increased the prices of fuel in December 2012. A second revision came in February, just three months later. Petroleum Industries Minister Anura Priyadharshana Yapa said the hikes were inevitable due to a CPC debt of Rs. 89 billion (his figure) and rising global crude oil prices.

Ironically, even when world market prices plummeted to unprecedented lows, adjustments in the local market were relatively moderate. Between November 7, 2008 and today, Sri Lankan consumers have not paid anything less than Rs. 133 for a litre of Octane 95 petrol; Rs. 115 for 90 Octane petrol; Rs. 73 for diesel; Rs. 88.30 for super diesel; and Rs. 50 for kerosene.

Prices are now the highest they have ever been — a litre of Octane 95 petrol is Rs. 170; Octane 90 petrol Rs. 162; diesel Rs. 121; super diesel Rs. 145; and kerosene Rs. 106.

Other dynamics come to play in determining these tariffs, experts warned. For instance, the CPC makes heavy losses on diesel and kerosene that cannot be covered by the taxes imposed on petrol. Fuel is reportedly provided to the public transport and power sectors at subsidised rates. Also, stocks are ordered in advance so world market fluctuations are not immediately reflected in domestic rates.

But add to everything the cost of payouts to banks with whom hedging contracts were signed and the CPC’s liabilities have increased. Last month, the Government paid the SCB US$ 60 million (Rs. 7.5 billion) to settle the five-year-old hedging dispute. This was much better than the US$ 180 million — $160 million plus 20 per cent interest — originally awarded to SCB by a British Court in November last year. Still, it is money that the Corporation, by its own admission, does not have.

This situation arose from the international banks — the SCB, Deutsche and Citibank — seeking international arbitration when the CPC stopped honouring its hedging agreements.Citibank’s case was heard in Singapore before an arbitration panel appointed by the London Court of International Arbitration. It upheld the CPC’s contention that the two contracts under which Citibank made its claim were beyond its (CPC’s) capacity and therefore entirely void.

The SCB case was heard in the London High Court. This time, the CPC lost with Justice Hamblen awarding the case to the bank on all counts. Court held the CPC liable to pay a minimum of the US$ 162 million due to the bank plus interest. The Sri Lankan Government appealed the ruling and lost again.

In November last year, the CPC lost its third case when a US-based arbitrator ruled in favour of Deutsche. The Corporation is now liable to pay US$ 60 million, plus interest, to the German bank.

Petroleum Minister Yapa was uncertain last week what the Government was doing regarding this payment “On the Standard Chartered case, the CPC has paid that money on the advice of the Attorney General,” he told the Sunday Times. “I think we appealed on the third one… it’s still going on, most probably.”

Such flippancy is surprising, given the astronomical amounts involved. It is providential for the CPC that Commercial Bank and People’s Bank —the two local financial institutions involve — have not filed action. At a news conference in February, Minister Yapa told journalists the ministry was confident of reducing the CPC’s debt by Rs. 50 billion by the end of this year.

Given his lack of information regarding the status of the colossal hedging payouts, it is unclear whether the minister had factored them into his calculation. Or whether, like those who had signed the agreements, he too had not read the fine print.

Finger-pointing: Easy way out

De Mel blames CPC’s legal officers; UK court ruling holds Cabinet also responsible

The Ministry of Petroleum Industries has paid a whopping Rs. 7 billion to Standard Chartered Bank as a settlement to the longstanding hedging dispute. This is Rs. 6.8 billion — Rs. 6,868,000,000 to be precise — more than the Ministry’s budgetary allocation for 2013.

The Government in its last Budget set aside just Rs. 132,000,000 (recurrent and capital expenditure) for the Ministry of Petroleum Industries.

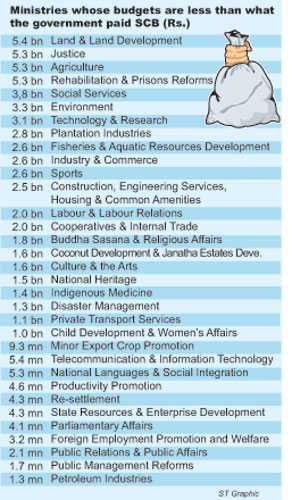

In all, 34 out of 52 ministries (including the President’s office) listed in the Appropriation Bill receive less than Rs. 7 billion as their annual allocation. For instance, notwithstanding the many natural disasters that have affected Sri Lanka in recent months, the Ministry of Disaster Management receives just Rs. 1.3 billion. The Ministry of Agriculture, currently beset by farmer protests over non-allocation of sufficient fertiliser, gets Rs. 5.3 billion.

The Ministry of Justice gets Rs. 5.3 billion; the Ministry of Cooperatives and Internal Trade, Rs. 2 billion; Ministry of Child Development and Women’s Affairs, Rs. 1 billion; the Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing and Common Amenities, Rs. 2.5 billion; and the Ministry of Social Services, Rs. 3.8 billion, to name a few.

The budgets of some ministries don’t even enter the billions. The Ministry of National Languages and Social Integration receives Rs. 5.3 million; Ministry of Resettlement, Rs. 4.3 million; and the Ministry of Public Management Reforms, Rs. 1.7 million. Political analysts pointed out that, given the piteous state of the CPC’s finances, the fuel-consuming public will eventually have to cover the losses incurred through the hedging deals. But where is the accountability?

In his ruling, upheld by a higher Court, Justice Hamblen dismissed the Government’s attempts to blame the contracts on Ashantha De Mel and Lalith Karunaratne, then Deputy General Manager of CPC. The judge rejected the argument that the two officials had entered into the agreements without authority. It was the Cabinet that had directed Mr. de Mel to carry out hedging without delay, he said.

It was also the Cabinet that had wanted Mr. De Mel to use the ‘Zero Cost Collar’ option. This effectively ensured that the CPC had no protection on the downside if oil prices dropped.

The Cabinet had instructed the CPC to “commence hedging with smaller quantities for a shorter period and gradually increase the quantity and the duration”. This, however, was not followed to the letter. Mr. De Mel told the Sunday Times that, “We were told the banks will help us to manage hedging. The CPC did not have any expertise in hedging. The banks told us we could get out of it.”

But when it came to signing the contracts, he had missed some of the fine print — particularly the exclusion clause that had said “in very small letters, like in an insurance form, that the banks were not advising us”. The onus for this must be borne by the CPC’s legal department, Mr. De Mel insisted. “The banks did not explain the contract properly,” he also said.

And it goes on. The finger-pointing shows that the Cabinet and a variety of officials were responsible for the losses arising from an experiment with a poorly-understood wagering instrument. Yet, the public alone picks up the tab.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus