Sunday Times 2

Democracy in reverse

NEW DELHI – Egypt has had a long and difficult couple of years. From January 25, 2011, when millions of people poured into the streets to rally against Hosni Mubarak’s regime, to the army’s recent overthrow of President Mohammed Morsi, the country has experienced a fall from euphoria into division and frustration — a pattern that seems to have become an inescapable feature of revolution. Was Egypt’s democratic transition doomed from the start?

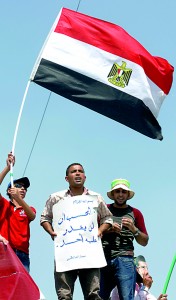

An Egyptian flag is displayed as supporters of ousted President Mohamed Mursi shout slogans during weekly Friday prayers at Rabaa Adawiya square. The sign reads: " Does he (referring to Egypt's coup leader) thinks that no one can subdue him". REUTERS/Louafi Larbi

Although Egypt’s revolution followed Tunisia’s, it was the successful overthrow of Mubarak’s regime that gave rise to the moniker “Arab Spring”. But, despite the country’s ostensible progress from Mubarak’s military-backed dictatorship to Morsi’s democratically elected government, it appears that not much has changed. Indeed, the army is now suppressing another “people’s revolt” – this time, by supporters of Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood.

With Egypt’s military restoring its grip on power, the country’s hoped-for political renaissance is slipping from view. Although plans for a new constitution and fresh elections in the next six months have been announced, the waywardness of the coup’s aftermath — reflected in the death of more than 50 protesters and the arrest of hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood supporters and their leaders — calls into question a democratic future.

External factors further undermine Egypt’s democratic prospects — and those of the Arab Spring countries that have viewed Egypt as a model. The brutal suppression of popular rebellion in Syria by President Bashar al-Assad’s Ba’athist government raises doubts that Arab countries will soon escape their legacy of oppressive leadership. On the contrary, the deepening in recent years of the long-standing Sunni-Shia schism throughout the Muslim world heralds further violence.

Given that the outcome of Egypt’s transition will have far-reaching consequences in the region, the country is under pressure from all sides. Saudi Arabia, for example, has embraced the military takeover, granting (together with the United Arab Emirates) $8 billion in immediate aid. As the Israeli novelist and essayist David Goldman put it, Egypt’s future now “depends on what happens in the royal palace at Riyadh, not in Tahrir Square.”

Saudi Arabian commentators have lauded General Abdul Fattah al-Sisi, the head of Egypt’s military. Asharq al-Awsat’s Hussein Shobokshi wrote, “God has endowed al-Sisi with the Egyptians’ love,” declaring that al-Sisi brought “true legitimacy to Egypt…after a period of pointlessness, immaturity, and distress.” Others speculated that, had the Muslim Brotherhood remained in office, Egypt would have become “North Korea on the Nile.”

Saudi Arabia’s involvement in Egypt suggests that a new pan-Arab fault line may be emerging, parallel to the Shia-Sunni one, with the Muslim Brotherhood on one side and the Sunni monarchies and secular military regimes on the other. If so, Egypt’s democratic prospects have not just dimmed; they have most likely been eliminated entirely.

This uncertainty may partly explain America’s hesitation to make any definitive policy decisions regarding Egypt. So far, the United Sates has refused to call Morsi’s overthrow a “coup” — thereby avoiding the domestic legal obligation to discontinue economic and military assistance while President Barack Obama’s administration examines its options.

White House Press Secretary Jay Carney explained that America’s relationship with Egypt “is bound up in America’s support for the aspirations of the Egyptian people for democracy, for a better economic and political future.” Translation: Any decision regarding US policy toward Egypt will be informed by US foreign-policy objectives, Congress, and US law.

But, by continuing to provide aid to Egypt, while neglecting to impose any concrete demands on Egypt’s new military leadership, the US has tacitly accepted the coup, which has made Egypt appear like a “banana republic.” Such an image cannot be useful in creating the kind of stable and outward-looking Egypt that the US wants as a cornerstone for regional stability.

Given the fragility of the Egyptian military’s position, and the ambiguity of US policy in Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood may now choose to wait patiently for an opportunity to regain control of Egypt’s government. But its commitment to democratic principles may be seriously weakened. One hopes that a recent comment by the deputy head of the Muslim Brotherhood’s political wing — “Do you know how many people died building the pyramids? How many died digging the Suez Canal?” – does not reflect the Brotherhood’s willingness to accept the most extreme levels of sacrifice in order to achieve its goals.

The stakes could not be higher for Egypt. Sheikh Ahmed el-Tayeb, the grand imam of Cairo’s Al-Azhar Mosque (the main seat of learning for Sunni Muslims worldwide), has warned of an impending civil war. Whether el-Tayeb is proved right depends on who has the final say in Egypt’s transition: the military, the Muslim Brotherhood, or a political force like the Salafist Al Nour party, which gained one-quarter of the vote in the last election and supported the military’s overthrow of Morsi.

Democracy is, by definition, the first casualty of Morsi’s downfall. The question now is whether the social rifts that the coup has opened — in Egypt and the wider Arab world — will become too deep to be bridged by any democratic path in the foreseeable future.

Jaswant Singh, a former Indian finance minister, foreign minister, and defense minister, is the author of Jinnah: India – Partition – Independence.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2013. Exclusive to

the Sunday Times

www.project-syndicate.org

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus